If it help, through the senses, to bring home to the heart one more true idea of the glory and the tenderness of God, to stir up one deeper feeling of love, and thankfulness for an example so noble, to mould one life to more earnest walking after such a pattern of self-devotion, or to cast one gleam of brightness and hope over sorrow, by its witness to a continuous life in Christ, in and beyond the grave, their end will have been attained.1

Thus Canon Charles Leslie Courtenay (1816–1894) ended his account of the memorial window to the Prince Consort which the chapter of St George’s Chapel, Windsor had commissioned from George Gilbert Scott and Clayton and Bell. Erected in time for the wedding of Albert’s son the Prince of Wales in 1863, the window attempted to ‘combine the two elements, the purely memorial and the purely religious […] giving to the strictly memorial part, a religious, whilst fully preserving in the strictly religious part, a memorial character’. For Courtenay, a former chaplain-in-ordinary to Queen Victoria, the window asserted the significance of the ‘domestic chapel of the Sovereign’s residence’ in the cult of the Prince Consort, even if Albert’s body had only briefly rested there before being moved to the private mausoleum Victoria was building at Frogmore. This window not only staked a claim but preached a sermon. It proclaimed the ‘Incarnation of the Son of God’, which is the ‘source of all human holiness, the security of the continuousness of life and love in Him, the assurance of the Communion of Saints’. The central lights depicted the Adoration of the Infant Christ, his Resurrection and Enthronement, teaching viewers that ‘as His human nature was glorified, so shall they too live, the same identical, individual beings as on earth’ ([Courtenay], pp, 5, 16).

The images around the central lights connected this Christocentric homily with the veneration of the dead Albert as a just ruler and a virtuous man. To the left side were Old Testament prophets and kings and to the right a selection of New Testament figures, whose ‘graces worked out by God’s Holy Spirit […] were by the same Spirit reproduced in him before our eyes’: John, St James the Less, St Bartholomew, St Barnabas, Nicodemus, the good centurion, Gamaliel, and St Timothy. Below were images of an idealized prince: ‘in converse with a labourer leaning on his spade’, representing Cambridge as its chancellor, ‘pondering over plans for the improvement of the dwellings of the poor’, cheering on the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, advising a sculptor, and superintending Trinity House, a charitable and mercantile institution ([Courtenay], pp. 19–20, 23). The window irradiated Albert’s deeds with the holiness of Christ, showing ‘how the Christian life is one, how earthly life passes into Heavenly, earthly service into Heavenly reward, but all in and from Christ’ (p. 27, emphases in original). The centre of this set of images, which showed Albert in the bosom of his family, was also its emotional core. Courtenay considered that even to describe them would ‘be treading too closely upon its sacredness, touching a wound that cannot be healed’ — Queen Victoria’s grief. All he would say is that these ‘memorials’ were ‘represented under the healing shadow of that Incarnate Lord, Whose taking upon Himself the ties and affections of our nature, gives to them their true blessedness, their real value, their continuance through all eternity’ (p. 25).

The east window of St George’s Chapel illustrates the productive interdependence of monarchy and Christianity in Victorian culture. ‘A family on the throne is an interesting idea’, argued Walter Bagehot in The English Constitution (1867): the idea not only made government ‘intelligible’, but almost holy. Impressed among other things by popular fervour for the marriage of the Prince of Wales, Bagehot argued that monarchy ‘strengthens our government with the strength of religion’, ‘enlisting on its behalf the credulous obedience of enormous masses’. Though confessing that ‘it is not easy to say why it should be so’, Bagehot advanced a functionalist explanation: adulation for the monarchy worked like a religion among an ‘uneducated’ people which ‘wants every now and then to see something higher than itself’.2 His was a doubly sceptical thesis. As a lapsed Unitarian, Bagehot regarded the wellsprings of religion as atavistic feeling, but he was a sceptic about monarchy too, and argued that Victoria’s symbolic power disguised her waning significance as a political player.3 To enquire too closely into what Victoria did all day would be to let in ‘daylight upon magic’ (v, 243). Yet the example of St George’s suggests that instead of simply accepting Bagehot’s argument that popular monarchism worked like a religion, historians should instead understand religion and monarchy as distinct but interlocking powers, exploring how Christian theology and aesthetics contributed to the articulation of monarchical ideology and vice versa. Throughout Victoria’s reign, religious communities of all kinds, from Anglicans to Jews, venerated Victoria, not in a dumb quest for ‘something higher’ than themselves, but because they felt that she exemplified the virtues and promoted the institutions they thought distinctive of their particular traditions. Behind ‘religion’ in Victorian Britain lay competing churches, sects, and religions whose theological priorities governed how they chose to represent their monarch in word and sometimes image.4 Courtenay’s Church of England was persistently, indeed increasingly, dominant among them, with the ‘high politics of symbolic representation’ that developed during the Thanksgiving for the Prince of Wales (1872), the Golden (1887) and Diamond jubilees (1897) anchored in ritualized visits to St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey.5

Words may seem the obvious source for investigating the ways in which Victoria represented the religiosity of her subjects. Every major event in her life and reign triggered a salmon run of sermons, turning her joys and sorrows into proof texts for the lives of ordinary believers.6 Yet the religious idealization of monarchy also left manifold material traces, notably the stained glass windows that are the focus of this article and most of which were destined for Anglican churches. It is important to remember that religion for the Victorians consisted in sensual experience and liturgical use of sacred places quite as much as in the study of sacred texts or in spoken and written attempts to frame and debate beliefs as ‘abstract mental processes’. As their ferocious disputes about the design and use of churches indicate, Victorians knew that art and architecture not only recorded but also advanced distinctive spiritual visions.7 Courtenay, the exegete of the St George’s window, exemplifies this religious investment in space. His friends had recommended him to the royal household as ‘High Church but not Puseyite’. An epigone of Samuel Wilberforce, he shared his sacramental romanticism and instinctively thought in typological and Incarnational ways.8 He was a champion of church restoration who felt that his generation had rediscovered that churches were not neutral spaces for ‘private edification’ but homes for the sacramental presence of Christ.9 Christ dwelled in ‘holy places’ just as he did in the lives of people such as Albert.

This article proposes that the stained glass windows memorializing major events in Victoria’s life are invaluable evidence for how Victorians thought about the relationships between throne and altar, taking as its point of departure Jasmine Allen’s insight that stained glass is an ‘ideological medium’.10 Victoria and her family were themselves active patrons of stained glass windows, which came second only to busts, portrait medallions, and photographs in their scrupulous memorialization of the dead.11 At Crathie Kirk near Balmoral, Victoria took a close interest in the windows of David and Paul installed to memorialize the Reverend Norman Macleod by his publisher Alexander Strahan. Finding photographs of the designs ‘distressing’ in their ugliness, she paid to have them replaced.12 After Victoria’s haemophiliac son Leopold died at Cannes, his widow Helena gave three windows to the Church of St George (1886–92) erected there as a memorial to him. When Victoria’s grandson Friedrich fell through her bedroom window in the Neues Palais at Darmstadt and died of his injuries (1873), his mother Alice replaced the panes with stained glass images of maternal love, grief, and self-sacrifice: a pelican feeding its young by pecking at its breast; Mary cradling her infant son and then holding the dead Christ. This was a private, even macabre example, but the eagerness of Christian communities throughout Britain, its empire, and the wider world to paint the monarchy in glass is striking. The most significant occasions for such memorials were the death of Albert (1861), the Golden and Diamond jubilees of 1887 and 1897, and the death of Victoria herself in January 1901. There were at least nineteen stained glass windows erected to Albert’s memory, while Jubilee windows went up in churches from St Margaret’s, Westminster to St Alban’s, Copenhagen.13 After her death, Victoria lingered on in glass at the furthermost ends of the British Empire. To give just one example, in April 1901 the parishioners of St Paul’s, Vancouver, a modest timber church in this frontier boomtown in British Columbia, voted for a memorial window to her. Richly caparisoned and clutching a scroll reading ‘God bless my beloved people’, she looks particularly lugubrious — perhaps because the local firm that made the window got the length of her life wrong.14

Having made the case for the importance of stained glass as a source for thinking about monarchy and religion, this article now shows how we might use such sources by concentrating on one such window, in St Saviour’s church, Southwark. It does so in the belief that paying close attention not only to memorials but also to their physical and institutional setting moves us beyond Bagehot’s rather condescending speculations and reveals the religious commitments that transfigured royal persons to have been not simple but complex, not merely instinctual and affective but considered and erudite. Not only was the window designed by Charles Eamer Kempe (1837–1907), a celebrated glass painter whose work is attracting renewed interest from scholars, but it formed part of an ambitious scheme to restore and redecorate St Saviour’s, which from 1905 has been known as Southwark Cathedral.15 The choice of St Saviour’s also illustrates the continued centrality of the established Church of England to the expression of religious monarchism throughout the nineteenth century. Whereas torrents of royalist text poured forth in equal volume from churches, chapels, and synagogues alike, wealthy patrons and subscribers tended to site stained glass windows in parish churches and cathedrals, which remained magnets for communal memory and civic patriotism.

‘The union of Church and State’: St Saviour’s, Southwark and its Jubilee window

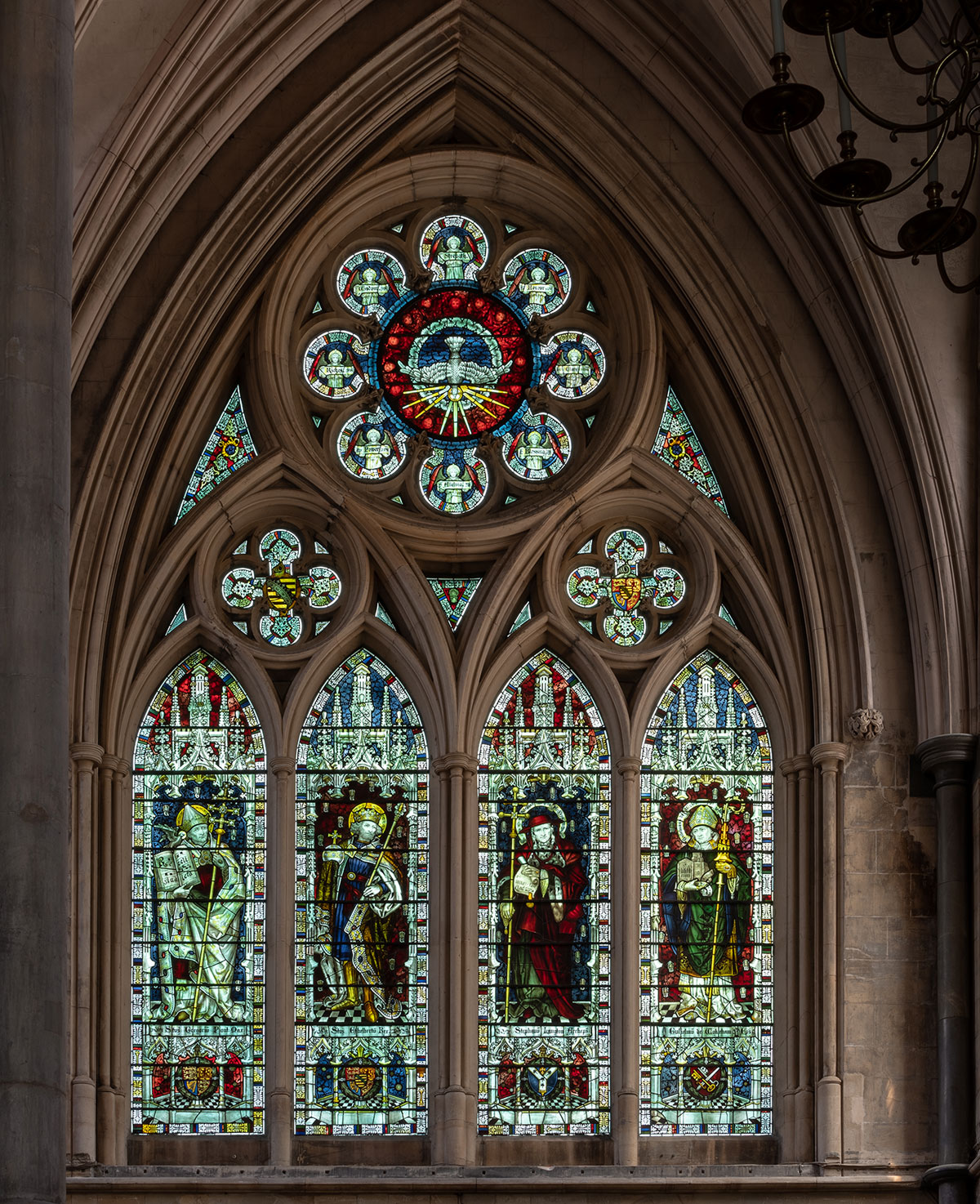

The press described the monument unveiled in the north transept of St Saviour’s on 22 June 1898 as a ‘memorial window to the Prince Consort’ (Fig. 1).16 This was perhaps surprising, for although Victoria had been obdurate in preference for marking events in her reign with reference to her dead husband, this practice had run into resistance and had generally been discontinued by the time of the Diamond Jubilee. Here it was appropriate because the window replaced an earlier memorial to the Prince Consort erected immediately after his death. The unveiling had been a solemn, hieratic occasion. Victoria and Albert’s son Arthur, Duke of Connaught went in procession up the nave as the choir chanted the 84th Psalm: ‘O how amiable are thy dwellings: thou Lord of hosts! | My soul hath a desire and longing to enter into the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh rejoice in the living God.’ For Anglicans, these words expressed how churches not only housed divine worship but actually manifested God’s presence. As the duke’s party arrived at the north transept, the singing of John Mason Neale’s hymn ‘Blessèd city, heavenly Salem’ amplified these sentiments, envisaging as it does Jerusalem as a material bridge between heaven and earth:

Vision dear of peace and love, Who of living stones art builded In the height of heaven above, And, with angel hosts encircled, As a bride dost earthward move!17

Edward Talbot (1844–1934), the Bishop of Rochester, in whose diocese St Saviour’s then lay, recited a prayer which acknowledged the window’s donor by commending ‘this gift of Thy servant, in memory of Albert, Prince Consort, now at rest’ and asked a blessing for the Queen and the royal family. After the duke had unveiled another couple of memorial windows — of which more later — Talbot delivered a sermon which drew together their subjects as moral and Christian exemplars:

When character is set on a hill, is raised to the Throne or to its side, then, indeed, in the fierce light of that high place, there is opportunity for such power of good and pure example […] as we remember thankfully to-day that God gave to England in the example and character of Albert, Prince Consort. When we see deeds of charity and public benefit, such as those which the other windows commemorate, their lesson and example, too, is effective and simple. (‘Memorial to the Prince Consort’)

Talbot’s sentiments were familiar from the ‘cult of the Prince Consort’ that had formerly gripped the country and expressed the hankering that Victorian believers of every creed and none felt for spiritual exemplars.18 The point of erecting windows and statues to the prince had not been simply to mourn him but to call his Christian virtues to mind. Decades earlier, the Duke of Connaught — then merely Prince Arthur — had gone to the Guildhall to unveil a stained glass window dedicated by the City to the ‘high and spotless character’ of the prince, which depicted him in an ‘attitude of meditation’ surrounded by the arts, virtues, industries, and institutions which he had fostered.19 Similarly, the patrons of the enormous statue of Albert in polished granite erected at Tenby in 1864 as the ‘Welsh national memorial’ to the Prince Consort meant their gesture not as ‘hero worship’ but as ‘an educational incentive to the practice of all excellence’. ‘May this memorial of departed excellence serve to impress us who are here present with a deeper sense of gratitude to thy fatherly goodness for one of the most precious of all the gifts Thou hast bestowed on our age and nation’, urged Connop Thirlwall (1797–1875), the Bishop of St David’s, at its unveiling. It was

the gift of one who, while he lived among us, was thy willing and untiring minister to us for good […]. May this image of his outward form help to keep alive in those who shall come after us, a thankful remembrance of this great blessing.20

Although the unveiling of the window offered one more ritualized opportunity to remember Albert, it contains no figurative depiction of him. This reticence was familiar from earlier memorials to him in churches. In Hardman & Co.’s memorial window to the prince in the east end of St Mary’s, Nottingham, only the inclusion of his coat of arms made a direct reference to him. Its actual subjects were scenes from the New Testament that indirectly alluded to Albert’s educational and philanthropic projects: widows lamenting the death of Dorcas; Christ healing the blind, blessing the children, and feeding the multitude; the shepherd finding the lost sheep and the Good Samaritan (Darby and Smith, p. 63). The window in St Saviour’s goes further, not only avoiding depicting Albert, but also making not even oblique allusion to his personal character. The only direct references to him are heraldic: shields contained in the quatrefoils below the window’s rose and below its panels, which depict the ancient arms of Saxony and those arms superimposed as an inescutcheon on the royal arms — a device adopted in 1893 to represent the succession of Albert’s sons to the duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.21

The window might better be read as a celebration of monarchy than a veneration of Albert. Canon William Thompson duly suggested in the second edition of his very popular history-cum-guidebook to the church that the window ‘may be regarded as illustrating the union of Church and State’.22 The rose at the top of the window, which depicted the Holy Spirit as a dove descending from heaven, surrounded by eight angels bearing the legend ‘Blessing, and glory, and wisdom, and thanksgiving, and honour, and power, and strength’, suggests that God has poured out his blessings on the throne.23 Below, four lights envisage an ancient, indivisible bond between a national church and monarchy. The first two lights showed Pope Gregory, who had sent Christian missionaries to England, and Ethelbert, the Kentish king who had embraced it with his encouragement. Thompson’s gloss presents Gregory less as a representative of Roman Catholicism than as a sensible administrator, who had ‘refused the title of Universal Bishop, calling it foolish and profane’ (p. 178). The next light showed Stephen Langton, the Archbishop of Canterbury under King John. Thompson understood him as at once a biblical educator and a ‘Christian patriot’ who had superintended England’s development as a constitutional monarchy: ‘His work still remains amongst us in the familiar division of the Bible into chapters, and in the Magna Charta — that grand palladium of English liberty and national freedom — which he was the chief means of wresting from King John’ (p. 179). Perhaps the most significant of these figures for Thompson is William of Wykeham, the founder of Winchester College, who was an ‘enthusiastic nationalist Churchman, […] a stout opponent […] of the Church of Italy’, and the ‘Father of the Public School system of this country’ (p. 179). Thompson quoted the invitation of the Anglican historian George Herbert Moberly to reflect on what that system ‘ha[d] made of Englishmen for the last five hundred years; what manliness and self-respect it has engendered, at the same time that it reproves eccentricities’ (p. 180). If Wykeham was a national exemplar, then he was also a local hero: St Saviour’s had belonged to the diocese of Winchester for most of its history until it had been transferred to Rochester in 1877.

Prince Albert had come to England as a rationalist Lutheran and together with Victoria had encouraged liberal Protestant forces in the Church of England. High Church folk often complained in consequence that ‘Court religion’ was ‘hazy’.24 Yet this memorial both to him and to Victoria’s jubilee had occasioned a dogmatic statement of the English monarchy’s tireless and faithful patronage of a Church which was Catholic in its antiquity and yet not papal. This embedding of the ‘union of Church and State’ in England’s Anglo-Saxon and medieval past reflected the growing confidence and erudition of a new generation of Anglican historians for whom the Church predated not only the Reformation, but the monarchy itself, whose development it had supposedly done much to foster.25 Jubilee windows often connected Victoria with the ancient succession of godly English monarchs. A public subscription funded a west window for Wedmore parish church in Somerset, which connected King Alfred to Victoria. Later Victorian scholars celebrated Wedmore as the site at which King Alfred had made a peace treaty with the baptized Viking Guthrum, thereby guaranteeing the integrity and Christianity of England. Its four lights contained figures of Alfred, William the Conqueror, Queen Elizabeth, and Victoria together with idealized scenes from their reigns: Alfred with Guthrum at his baptism at Athelnay and at Wedmore; Harold swearing fealty to William and the Battle of Hastings; Raleigh spreading the cloak for Elizabeth and the Armada; Victoria’s coronation and her life with her family.26 Kempe’s Diamond Jubilee window for the east window of the Lady Chapel in Winchester Cathedral, which Victoria’s daughter Beatrice unveiled in 1898, featured Victoria kneeling in prayer and surrounded by a host of monarchs: Elizabeth of York, the wife of Henry VII, King Alfred, King Cnut, Kynegils, the first Christian king of Wessex, and Edward the Confessor. As in Southwark, they stand with clerics to represent the union of Church and State, including William of Wykeham once more.27 A memorial window to Victoria in Hereford Cathedral coupled her with Ethelbert, the Saxon king who also featured in St Saviour’s.28 These windows present English history as a frozen pageant of idealized people and incidents: one of those reassuring visions of the deep continuity of the State that came to dominate the Victorian culture of the past.29

The St Saviour’s window also took its place in a building that was being remade to conform to High Church visions of what a church should be. The donor of the window, Frederick Lincoln Bevan, was a deep-pocketed Oxonian banker and a director of Barclay and Perkins brewery who on his death in 1909 left an estate worth ten million pounds in today’s money.30 He belonged to the Restoration Committee, which aimed to reverse what it regarded as the earlier mutilation of the church by Charles Sumner (1790–1874), the Bishop of Winchester. Sumner had initiated the rebuilding of the crumbling nave on fashionable Gothic lines in 1838. A rising generation of ecclesiologists, who stood for a more exacting and scholarly vision of the Gothic, had attacked his efforts as a botch job. Augustus Welby Pugin alleged that he had created ‘as vile a preaching-place as ever disgraced the nineteenth century’ and wept over ‘this desecrated and mutilated fabric, […] this sacrilegious and barbarous destruction’ (Thompson, pp. 246, 247).

Anthony Thorold’s appointment to the bishopric of Rochester in 1877 had marked the end for Sumner’s nave and its now improper galleries. Thorold (1825–1895) regarded Rochester as the ‘Cinderella of English dioceses’, a sprawling, incoherent expanse recently expanded to incorporate much of unchurched South London. He wished to make St Saviour’s the headquarters for a spiritual crusade against ‘gross animalism or dismal unbelief’.31 Thorold, like Sumner, was an evangelical who detested the Ritualists who sought to introduce elements of contemporary Roman Catholicism into the Church’s worship. His own son’s defection to Rome in 1884 only increased his distaste for them (Simpkinson, p. 252). Yet he considered that the best defence against Rome was ‘not [to] despise her, for nothing serves her purpose so well’, but to redouble the work of evangelization. His clergy could gain strength in doing so by ‘cling[ing] fast to that great and unique English communion whose future opens such magnificent promise, even as its roots are struck so deeply in the remote past of English history’ (Thorold, pp. 64, 65). To restore St Saviour’s was therefore ‘no mere fad or craze of antiquarianism’ but a symbol of his determination to show that the Church could still thrive in London. Even High Churchmen such as Henry Parry Liddon, who disliked his anti-Ritualist sallies, commended his determination to build a ‘central church (of some kind) for the South of London’ (Simpkinson, pp. 282, 136). Having wrested control of the living from its parishioners and appointed Thompson, its last chaplain, as its first rector, he sought funds for the restoration of its fabric. In 1890 Arthur Blomfield (1829–1899) began rebuilding the nave and south transept, with the Prince of Wales laying the foundation stone. The son of a briskly High Church Bishop of London and a wealthy brewer’s daughter, Blomfield was a dab hand at church restoration, an exporter of Gothic cathedrals for Guyana and the Falkland Islands, and a servant of royalty, who had remodelled St Mary Magdalene, Sandringham for the prince and built a memorial church to Victoria’s son Leopold in Cannes.32 Once his work was complete in 1897, St Saviour’s became a collegiate church and a pro-cathedral, but its costly transformation continued, supported by such patrons as Bevan and Sir Frederick Wigan, the first treasurer of the cathedral. In June 1898 the Duke of Connaught had not only unveiled stained glass windows, but also started the church’s costly new clock and inaugurated its pulpit and a lectern. The congregation assembled for the service dug into its pockets to contribute towards the £12,000 still needed for further works (‘Memorial to the Prince Consort’, p. 5).

Blomfield’s mission at St Saviour’s was not to pursue an abstract ideal of Gothic purity. Though a Gothic Revival architect, his intentions were historicist and pragmatic: to recuperate the surviving medieval fabric and use it as the foundation for an ‘early English’ design.33 Charles Eamer Kempe, the prolific designer of the memorial window and of many others in the church, was a natural ally in this enterprise. Although Kempe had trained with Clayton and Bell, he had drifted from early medieval styles towards the more painterly qualities of German fifteenth-century glass, just as architects such as Blomfield and his early collaborator George Frederick Bodley were turning from early French to the study of English and German Gothic.34 Martin Harrison has argued that Kempe’s work tailed off in quality by the time he produced this window, generating figures that were ‘flabby and over-bejewelled, fleshy and mannered in draughtsmanship’ and ‘enmeshed in a mass of complex, over-wrought canopy work’.35 Kempe’s defenders by contrast emphasize his complex and refined grasp of scriptural typology.36 In his day, his admirers liked the clarity of his windows, his rich colours, and their transparency to light. He was popular as a maker of memorial windows to great men and local heroes. In 1874 the massed choirs of Folkestone sang at the unveiling of Kempe’s window to William Harvey in its parish church, which the medical profession had paid for; while Lord Rosebery and Arthur Balfour were among the subscribers for his memorial window to Jane Austen in the north nave of Winchester Cathedral.37 In November 1890 the friends of Guy Dawnay, a swashbuckling MP gored to death by a buffalo during an African big game hunt, unveiled a window to him by Kempe in York Minster. It featured St George of England and St Oswald, ‘both brave and adventurous men’, the latter associated with the northern St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne.38 In 1897 Kempe installed six stained glass windows in the Bedford Chapel of St Michael’s, Chenies, in which Renaissance figures celebrated the virtues of the members of the Russell household buried there.39 The royal family had taken up Kempe. In 1877 he travelled to Darmstadt at Princess Alice’s bidding to install a memorial window to her dead son Friedrich in the Rosenhöhe mausoleum there (Stavridi, p. 27). The Prince and Princess of Wales had inspected this design and it was therefore natural that they commissioned Kempe to produce a memorial window to their son the Duke of Clarence after his death from influenza in 1892. Portraying the duke as St George, the model of Christian knighthood, it was initially installed on the Ministers’ Staircase in Buckingham Palace and is currently on display in the Stained Glass Museum at Ely.40

Although Kempe appealed across the religious spectrum, he was fiercely Tractarian. He may have been educated at Rugby School and later designed a memorial window to Edward White Benson in its chapel, but he did not take to its muscular Christianity.41 He was bad at Classics and appeared as ‘the Tadpole’ in Tom Brown’s Schooldays, a weedy friend of Tom’s, named for his ‘great black head and thin legs’ (Stavridi, p. 14). He left Pembroke College Oxford a mannered, firmly unmarried High Churchman of delicate sensibilities who wished to be a priest before his stammer ruled that out. Although wealthy brewers bankrolled the rebuilding and redecoration of St Saviour’s, Kempe initially blanched at including the Tabard Inn in his Geoffrey Chaucer window (1900). Even Thompson could not resist teasing ‘our artist’ who ‘always lives high up amid Saints and Angels’, joking that ‘our Saviour would have been born in an Inn, had there been room’ (p. 195). At his exquisite country house at Lindfield in Sussex, Kempe clashed with wardens of the parish church over his plans to replace box pews with benches and screen off the chancel. Foiled, he fitted up a room of his house as an ‘oratory’ and held prayers for his servants there instead. His early forays into South London had been provocative: he worked on windows for the now demolished churches of St Paul’s, Lorrimore Square and St Agnes, Kennington for the Reverend John Going. Bishop Thorold deeply distrusted Going’s churchmanship — so much so that the installation of a window to the Virgin Mary at St Agnes was held up for several months by fierce disputes with the bishop over how wide her halo could be (Stavridi, pp. 40–42, 62).

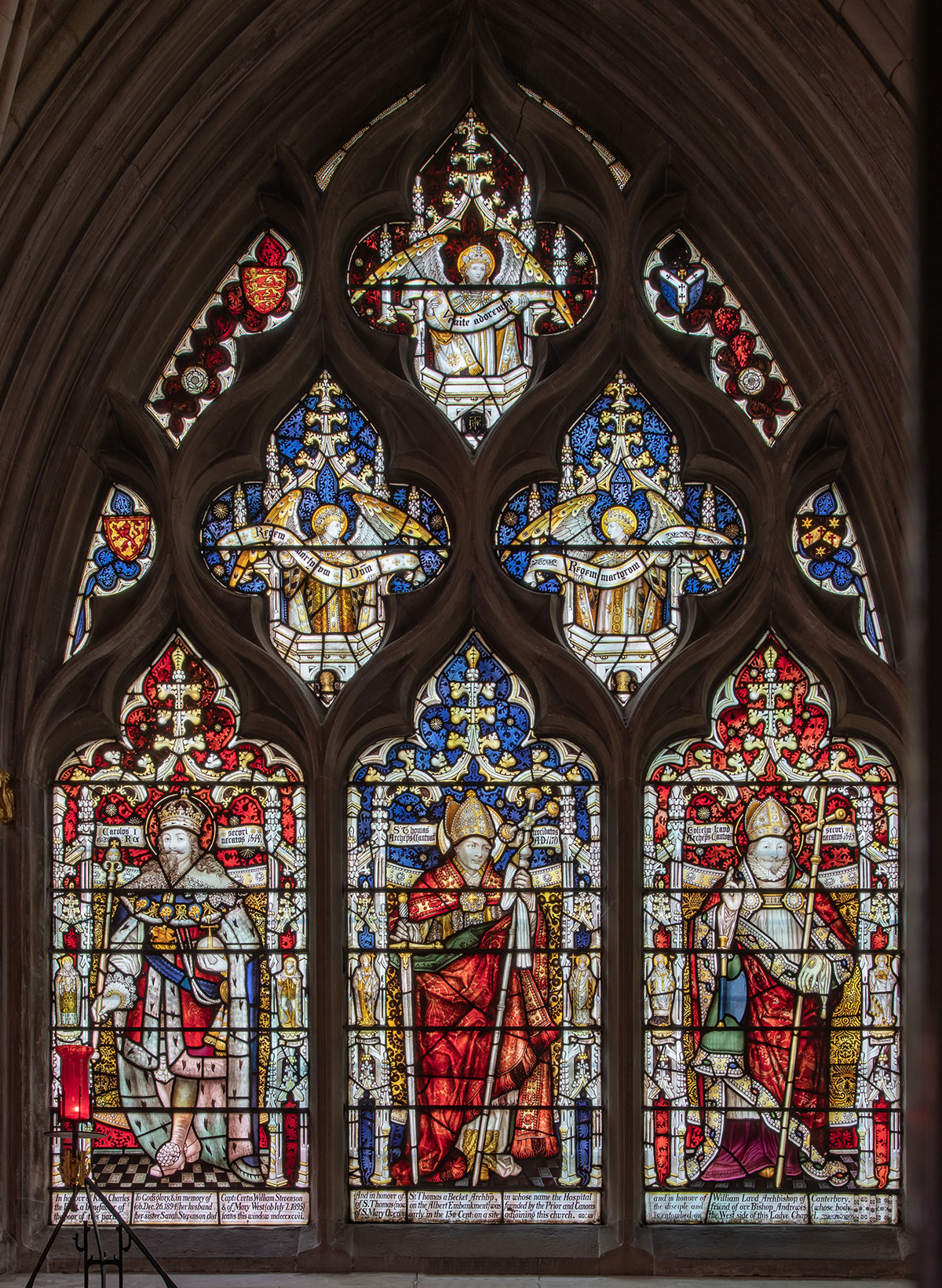

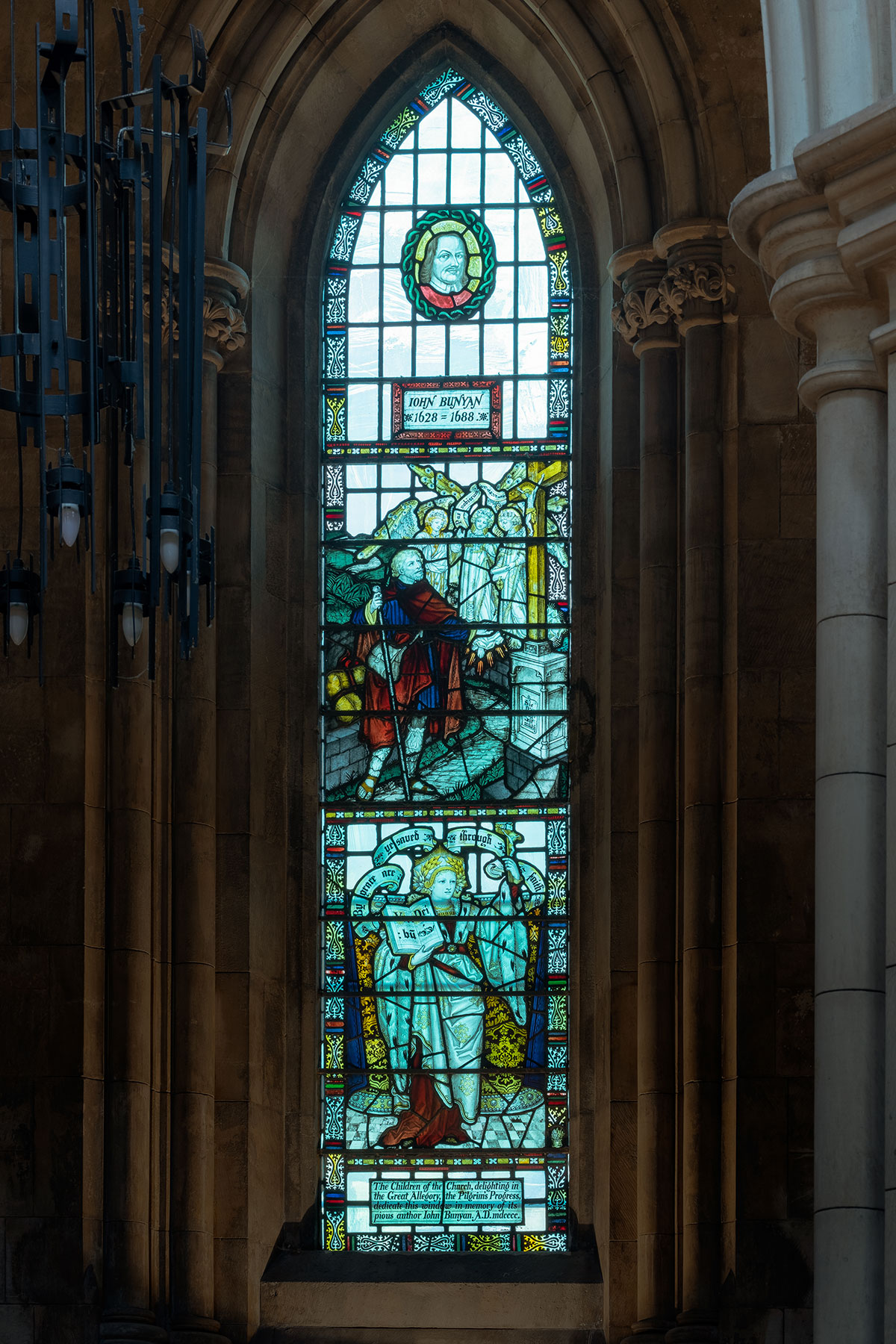

Kempe’s churchmanship matched the vision of William Thompson, the scholarly and High Church rector of St Saviour’s. The Albert memorial from the start took its part within a complete scheme for new windows to be implemented as funds became available: Kempe’s planning book shows the nave parcelled up among divines and writers from Massinger to Bunyan.42 This scheme both celebrated the place of St Saviour’s in the history of South London but also expressed Thompson’s High Church proclivities, which are everywhere in his guidebook. Thompson, for instance, felt tepidly about the mid-Victorian windows he had inherited in the retro-choir that commemorated the men he called the ‘Anglican martyrs’ under Mary. He felt that they supported readings of the church’s history that wrongly emphasized its ‘Protestant’ character (p. 53). He was keener on the Kempe window (1897) in the same chapel, a ‘masterpiece’ that celebrated ‘martyrs of another school’: Thomas Becket, Charles I, and William Laud (Fig. 2). Thompson’s guidebook deeply admires Laud, citing the Anglican historians J. B. Mozley and Mandell Creighton against the flippant Macaulay to establish him as a tolerant reformer of the English Church. Similarly, Charles I was the ‘white king’ who had died for the Church.43 Kempe too was Caroline rather than Hanoverian in his monarchism: his house at Lindfield had windows of Charles I and Laud (Corpus, ed. by Collins, p. 276). Thompson’s history similarly singled out the early eighteenth-century chaplain Dr Henry Sacheverell, a byword for Tory bigotry, as one who had ‘saved the Church of England’ (p. 145). In March 1906 Thompson unveiled a window that likened Sacheverell to St Paul: heroically testifying before Agrippa the representative of the State and in the lower panel holding both the instrument of his martyrdom and the epistle which had provided the text for Sacheverell’s most incendiary sermon. Such was Thompson’s Anglican imperialism that he hastened to assure viewers of the window to John Bunyan (Fig. 3) that he ‘WAS A CHURCHMAN at heart, and that he never ceased to value the Ordinances of the Church’ (p. 230).

Yet visitors to St Saviour’s could also have connected Albert’s window to other, more inclusive narratives of religion and monarchy which ran along its walls. The first was a cosmic rather than a parochial history of salvation. Facing the Jubilee window in the south transept was another grand Kempe effort: a Tree of Jesse commissioned by Sir Frederick Wigan as a memorial to a dead relative.44 Destroyed in the Second World War, it was for Thompson a compelling statement of Christ’s monarchical lineage, binding together the Old and New Testament subjects found throughout the church into a story of ‘progress and continuity, the union and continuity of Divine Revelation’. This scheme culminated in a great east window by Kempe, which depicted the Crucifixion, and a west window by Henry Holiday, depicting the Creation. Taken together, they reminded Thompson that to come into church was to enter the presence of ‘a Monarchy, even the Son of God, King of Kings’ (Corpus, ed. by Collins, pp. 22, 322).

The second narrative was national and local rather than ecclesiastical. For the nave, Thompson and Kempe produced windows that featured writers with local connections, from John Gower and Geoffrey Chaucer to Oliver Goldsmith and Dr Johnson. The effect was both to root St Saviour’s in its locality and to make it a literary pantheon, a miniature Westminster Abbey that was all Poets’ Corner. The most celebrated were a set on the south side of the nave devoted to giants of Elizabethan drama: Edward Alleyn, Beaumont and Fletcher, Massinger, and Shakespeare. These windows created a composite picture of the English as a literary but also Bible-reading nation. Beaumont’s window alluded to his partnership with Fletcher by portraying David and Jonathan; Massinger’s portrayed a subject from his play, The Virgin Martyr, and the Shakespeare window cited Wisdom 8. 4, ‘Doctrix disciplinae Dei, et electrix operum illius’ (‘For she is privy to the mysteries of the knowledge of God, and a lover of his works’). Thompson’s gloss made the case for Shakespeare’s profound indebtedness to the Bible, arguing that he was a sincere Anglican, whose works ‘trained and exercised men’s minds to virtue and religion’ (p. 296). These windows prized philanthropic effort over worldly power or literary brilliance. In the Alleyn window, which the Duke of Connaught had unveiled with the Albert memorial, Kempe remembered not the gifted actor but the educational pioneer, a fit parallel to William of Wykeham. The left-hand panel featured a figure of Charity and quoted Psalms 34. 11 — ‘Come, ye children, hearken unto me: I will teach you the fear of the Lord’ — while the right-hand one showed Alleyn in the act of founding Dulwich College.

These values appealed to St Saviour’s donors as well as to one of Thorold’s most influential successors — Edward Talbot, the preacher at the unveiling of the Jubilee and Alleyn windows. Talbot was a liberal High Churchman. Brought up in a family enthused by Tractarianism, Talbot escaped its excesses by virtue of his formative reading of John Stuart Mill and other liberal thinkers as an undergraduate.45 His sermons and charges as Bishop of Rochester hailed a ‘great revival of the Church idea’ as an ‘organic’ alternative to the exploded heresies of ‘Manchesterism and individualism’. Yet he warned his clergy to avoid ‘Ecclesiasticism’, ‘personal Pharisaism’, or specialized ‘lingo’. It was very important to ensure that in their pursuit of liturgical correctness church people did not fall into a ‘mere medievalism’ which cut them off from the sympathies and vocabulary of ordinary people.46 In November 1894 Bevan and Wigan had been among the worthies gathered to inaugurate St Saviour’s Public Library on Southwark Bridge Road. Designed ‘to brighten the lives of the poorer classes’, it took a step towards fulfilling Talbot’s determination to fix the ‘want of correspondence between man and God’s Word to man as that word is spoken through her to the Londoner or dockyard man or country man of to-day’.47

If the Diamond Jubilee window celebrated the union of Church and State, throne and altar, then that union was supposed to put the promotion of the common good above ecclesiastical exclusivity and plane down the ‘harsh distinctness’ that had formerly separated evangelical and Ritualist clergy in Talbot’s diocese (Talbot, Vocation, p. 17). On 16 February 1897, during a ceremony to mark the reopening of St Saviour’s after renovation and its inauguration as a pro-cathedral, Talbot’s immediate predecessor as Bishop of Rochester, Randall Davidson, had urged that

no one set or sort of Churchmen are to monopolise this hallowed ground […]. There are not many Churches, perhaps, in Christendom whereon more distinctly than here the changing centuries have set their marks and taught us how varied is the Church’s mission to the world, how widely different the workmen to whom, in the long course of the Church’s day, the Lord of the vineyard has given their several tasks. (Thompson, p. 309)

The emphasis was on St Saviour’s as a church that contained multitudes and in doing so was a synecdoche for the national Church. It came naturally to Davidson, a Scot raised as a Presbyterian before rising smoothly through the Church’s ranks thanks to his friendship with Queen Victoria. If the history embedded in the stones and shining in the windows of St Saviour’s was a solvent of sectarian differences, then so too was monarchy. Months after Davidson’s sermon, Talbot preached one on Jubilee Sunday on ‘The Ministry of Monarchy’. He hailed Queen Victoria as ‘a personal example to us of faithful piety’, who had united her people through sympathy and admiration for the griefs she had disclosed to them.48 The throne was no empty totem and Britain was more than a crowned republic. Talbot swiped at the ‘cynics’ who will ‘carp and scoff at loyalty to the throne, and say that the Crown is a name and the people rule’ (Sermons, p. 34).

This article has offered a close, contextual reading of just one stained glass window in order to confirm Talbot’s point. ‘Loyalty to the throne’ in Victorian Britain and its rhetorical and material expressions were more than just the product of formless religious urges. Victoria did not dazzle the people; she represented them and their religiosity. Ecclesiastical commitments both inspired and shaped monarchism in Victorian Britain. When Thompson, Bevan, and Kempe came together as churchman, patron, and artist at St Saviour’s to remember Albert and to commemorate the jubilee, they did so because they saw monarchy as the servant of their church, which in their eyes had been the indivisible ally of godly monarchs since the dawn of English history. This was a distinctive vision, but, as a fuller consideration of St Saviour’s decorative scheme has suggested, it was an expansive and inclusive one. The monarchy served the Church, but that Church was worthy of respect because like St Saviour’s itself it was a pantheon of arts and a museum of history as well as a temple. Further consideration of other windows might similarly show us that people who felt reverence for Queen Victoria and the monarchy always refracted it through their ecclesiastical, political, and social commitments. Therein arguably lay the magic of the Victorian monarchy.

Notes

- [Charles Leslie Courtenay], The Memorial Window in St George’s Chapel: Its Spirit and Details (Eton: Ingalton and Drake, 1863), pp. 29–30. [^]

- Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution (1867) and ‘The Thanksgiving’ [1872?], in The Collected Works of Walter Bagehot, ed. by Norman St John-Stevas, 15 vols (London: The Economist, 1965–86), v: The Political Essays (1974), 230, 232, 233, 440, emphasis in original. [^]

- See J. C. D. Clark, ‘The Re-Enchantment of the World? Religion and Monarchy in Eighteenth-Century Europe’, in Monarchy and Religion: The Transformation of Royal Culture in Eighteenth-Century Europe, ed. by Michael Schaich (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 41–75. [^]

- For a fuller statement of this argument, see Michael Ledger-Lomas, This Thorny Crown: A Spiritual Life of Queen Victoria (Oxford University Press, forthcoming). [^]

- William M. Kuhn, Democratic Royalism: The Transformation of the British Monarchy, 1861–1914 (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1996), pp. 12–13, 82. [^]

- See, for example, John Wolffe, Great Deaths: Grieving, Religion, and Nationhood in Victorian and Edwardian Britain (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000) on funeral sermons for royals. [^]

- William Whyte, Unlocking the Church: The Lost Secrets of Victorian Sacred Space (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 22–24 (p. 24). [^]

- Thomas Acland to Robert Peel, 28 March 1843, Peel Papers, London, British Library, Add MS 40436, fol. 164; Charles Leslie Courtenay, God’s Work and God’s Glory: Preached on the Sunday after the Funeral of the Right Reverend Samuel, Lord Bishop of Winchester (Eton: Drake, 1873). [^]

- Charles Leslie Courtenay, The Presence of Christ with His Ministry in Holy Places — Two Sermons (London: [n. pub.(?)], 1854), pp. 21–25. [^]

- Jasmine Allen, Windows for the World: Nineteenth-Century Stained Glass and the International Exhibitions, 1851–1900 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), p. 152. For memorial windows in general as sources for Victorian attitudes, see Jim Cheshire, Stained Glass and the Victorian Gothic Revival (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), pp. 26–27, 84, 101, 144, 147, 166–68; and Michael Kerney, ‘The Victorian Memorial Window’, Journal of Stained Glass, 31 (2007), 66–93. [^]

- See Jonathan Marsden, Victoria and Albert: Art and Love (London: Royal Collection, 2010) for an overview of their patronage; and Anne M. Lyden, Sophie Gordon, and Jennifer Green-Lewis, A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography (Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 2014). [^]

- Windsor, Royal Archives, VIC/MAIN/D13A, fols 165–225 contain extensive correspondence on the Crathie windows. When the old Crathie Kirk was demolished, the windows were transferred to the new building (1895). See Douglas Morgan, Windows on Crathie: Notes on the Stained Glass Windows in Crathie Parish Church, Aberdeenshire (London: Arabesque, 1995). [^]

- ‘Ecclesiastical Intelligence’, The Times, 21 April 1898, p. 8; Elisabeth Darby and Nicola Smith, The Cult of the Prince Consort (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983), p. 112. [^]

- Author’s information. [^]

- Adrian Barlow, Kempe: The Life, Art and Legacy of Charles Eamer Kempe (Cambridge: Lutterworth, 2018); and Barlow, Espying Heaven: The Stained Glass of Charles Eamer Kempe and his Artists (Cambridge: Lutterworth, 2019). [^]

- ‘St Saviour’s Southwark’, Morning Post, 23 June 1898, p. 4; ‘Memorial to the Prince Consort’, Standard, 23 June 1898, p. 5. [^]

- ‘Blessèd city, heavenly Salem’, in Hymns Ancient and Modern for Use in the Services of the Church, comp. by William Henry Monk (London: Novello, 1866), no. 243. [^]

- See Darby and Smith; and Making and Remaking Saints in Nineteenth-Century Britain, ed. by Gareth Atkins (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016). [^]

- ‘Royal Visit to the City’, The Times, 4 November 1870, p. 12. [^]

- An Account of the Welsh Memorial Erected to His Royal Highness the Prince Consort as a Mark of Loyalty to Her Most Gracious Queen, and of Affectionate Respect and Gratitude to the Memory of Albert the Good (Tenby: Mason, 1866), pp. 26, 47. [^]

- ‘Southwark St. Saviour: North Transept’, Commission Book, C. E. Kempe and Co. Ltd Archive, London, Victoria and Albert Museum, AAD 2/2–1982, fol. 290. My account of the shields adopts the detailed suggestions of the referee for 19. [^]

- William Thompson, Southwark Cathedral: The History and Antiquities of the Cathedral Church of St Saviour, 2nd edn (London: Ash, 1906), p. 177. [^]

- The referee for 19 notes that Kempe has changed the masculine ‘might’ to ‘strength’, perhaps to better fix the quotation on the Queen. [^]

- Review of The Early Years of His Royal Highness the Prince Consort, comp. by Hon. C. Grey (1867), Christian Remembrancer, October 1867, pp. 326–52 (p. 349). [^]

- See James Kirby, Historians and the Church of England: Religion and Historical Scholarship, 1870–1920 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016). [^]

- ‘A Memorial to King Alfred’, Daily News, 12 September 1890, p. 6. [^]

- The Corpus of Kempe Stained Glass in the United Kingdom and Ireland, ed. by Philip N. Collins (Liverpool: Kempe Trust, 2000), p. 102; ‘Winchester Cathedral: Description of the Royal Jubilee Memorial Window’, in Lisle Portfolio, vol. ii, London, Victoria and Albert Museum AAD/1995/2, fols 235–36. [^]

- ‘Ecclesiastical Intelligence’, The Times, 10 May 1902, p. 8. [^]

- See, for example, Billie Melman, The Culture of History: English Uses of the Past 1800–1953 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006). [^]

- ‘University Intelligence’, Standard, 14 May 1864, p. 6; ‘Death of Mr F. L. Bevan’, Financial Times, 26 October 1909, p. 5. [^]

- C. H. Simpkinson, The Life and Work of Bishop Thorold: Rochester 1877–91, Winchester 1891–95 (London: Isbister, 1896), pp. 73; Anthony W. Thorold, A Charge Delivered to the Clergy of the Diocese of Rochester, at the Primary Visitation in 1881 (London: Murray, 1881), p. 36. [^]

- Paul Whitehouse, rev. by John Elliott, ‘Blomfield, Sir Arthur William (1829–1899)’, ODNB, <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/2667>. [^]

- George Worley, Southwark Cathedral, Formerly the Collegiate Church of St. Saviour, otherwise St. Mary Overie (London: Bell, 1905). [^]

- See Michael Hall, George Frederick Bodley and the Later Gothic Revival in Britain and America (London: Yale University Press, 2014). [^]

- Martin Harrison, Victorian Stained Glass (London: Barrie & Jenkins, 1980), p. 71. [^]

- See Barlow, Espying Heaven. [^]

- ‘Memorial to Harvey’, Western Mail, 10 April 1874, p. 6; ‘In Honour of Jane Austen’, Southampton Herald, 30 August 1899, p. 1; Corpus of Kempe, ed. by Collins, p. 102. [^]

- ‘The Late Hon. Guy Dawnay’, York Herald, 8 November 1890, p. 2. [^]

- Margaret Stavridi, Master of Glass: Charles Eamer Kempe 1837–1907 and the Work of his Firm in Stained Glass and Church Decoration (Hatfield: Taylor Book Ventures, 1984), p. 108. [^]

- ‘Prince and Princess of Wales’, Morning Post, 20 March 1877, p. 5; London, Royal Collection Trust, ECIN 69046. [^]

- ‘The Archbishop of Canterbury at Rugby’, The Times, 5 October 1898, p. 6. [^]

- ‘Southwark: Collegiate Church of St Saviour’, Book of Church Plans, Kempe and Co. Archive, Victoria and Albert Museum, AAD/1982/2/41, fol. 47. [^]

- Thompson¸ pp. 88–100; Corpus of Kempe, ed. by Collins, pp. 179–80. [^]

- It is suggestive that Kempe’s Diamond Jubilee window for Winchester Cathedral had actually depicted Victoria kneeling in prayer below a Tree of Jesse. [^]

- Edward Talbot, Memories of Early Life (London: Mowbray, 1924), pp. 10, 37–45. [^]

- Edward Stuart Talbot, The Vocation and Dangers of the Church: A Charge Delivered to the Clergy of the Diocese of Rochester at his Primary Visitation (London: Macmillan, 1899), pp. 51, 50, 55, 70, 91, 107. [^]

- ‘St Saviour’s Public Library’, The Times, 3 November 1894, p. 11; Talbot, Vocation, p. 12. [^]

- Edward Talbot, Sermons at Southwark, Preached in the Collegiate Church of St Saviour (London: Nisbet, 1905), pp. 32–33. [^]