On 29 November 2011 the British ambassador’s residence in Tehran was stormed by Iranian protesters in retaliation for economic sanctions imposed by the UK over Iran’s nuclear programme.1 Works of art from the Government Art Collection (GAC) on display in the residence suffered considerable damage.2 Of the six works that had been on display, it seemed clear that a form of iconoclasm had been enacted: modern works had been ignored while historical royal portraits, including an important nineteenth-century Qajar portrait of Fath ’Ali Shah by Ahmad had been slashed. The most extreme violence, however, was directed towards the British royal portraits of Victoria, her son King Edward VII, and grandson King George V.3 The damaged paintings included an autograph portrait of Queen Victoria by George Hayter.

When the crowd of protesters scaled the British compound wall in Tehran in November 2011, the first indications of the extent of the damage to the embassy building and its contents were revealed in press reports, including the publication of an arresting image of Hayter’s painting after it was torn.4 Having glimpsed the destruction, little could be achieved in the immediate aftermath. The moment British Embassy staff were safely airborne, the Foreign Secretary expelled all Iranian diplomats based in London and political ties between the two countries were cut.5 The British Embassy remained closed for the next four years. For a collection whose aim is to contribute to cultural diplomacy through works of art displayed in UK embassies and high commissions around the world, the attack on the Tehran Embassy had lasting consequences as damaged works were stranded there for several years following severance of diplomatic ties between the two countries. In 2016, following the gradual reinstatement of diplomatic relations, it became possible for GAC staff to visit Tehran and examine the damaged works of art. Fragments of the Victoria portrait, saved by local staff, were reassembled like a jigsaw from which it was possible to determine that almost all the original paint surface from the portrait was extant. This raised hopes that restoration could be successful if the damaged works could be returned to the UK for treatment.

Repatriating the art was itself challenging because continuing political sensitivities compounded the practical difficulties of safely moving the fragile pieces. Following lengthy negotiations, in early 2018 Victoria left the British Embassy for the first time in a hundred and fifty years and returned, ingloriously, to the UK.6 Over the next nine months, the portrait underwent a remarkable process of restoration and, looking beyond the immediate structural damage, the condition of the paint layer was untouched. Cleaning it was transformational (Fig. 1).7 The restoration project also provided a unique opportunity to carry out primary research on the history of this painting, the context of its making, and to establish how Hayter became involved with this commission for the British legation building in Tehran.

This article will explore the longer history of the painting from its making, through the significance of its presence in nineteenth-century Tehran, to the 2011 attack and its reinstatement in 2019. While uncovering new archival material that will help to situate this portrait within the wider context of Hayter’s corpus of autograph copies of Queen Victoria’s state portrait, and to shed light on his so far unexplored connections with Iran, its examination will also explore what this work conveys about the complex history of British and Iranian diplomatic relations.8 Moreover, the account of the conservation and reinstallation of the painting will emphasize its continued significance; that this is not just an historical artefact but one, like Victoria’s image more generally, that has a dynamic and evolving connection with contemporary politics and diplomacy (Fig. 2).9

The son of miniaturist Charles Hayter, George Hayter (1792–1871) studied painting at the Royal Academy Schools and in Rome, specializing in portraiture and history painting. Admired and held in the highest regard by Victoria as ‘the best portrait painter’, Hayter secured an official position within the royal household which allowed him to undertake significant commissions.10 In a diary note from 9 August 1857, he recounted: ‘On this day 1837, I was appointed Principal Painter of Portraits and History to the Queen, but had to wait till the death of Sir David Wilkie for the enjoyment of my office.’11 Scottish artist David Wilkie had been a favourite of George IV and continued his role as official painter through to Victoria’s accession. However, he fell out of favour with the Crown over two commissions: The First Council of Queen Victoria, a painting that the Queen subsequently referred to as ‘one of the worst pictures I had ever seen, both as to painting & likeness’; and her state portrait which she described as ‘atrocious’.12 Consequently, she decided to entrust the commission for a new state portrait to Hayter. Painted c. 1838–40 and now on display at the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh, it depicts the 19-year-old Victoria as she appeared on her coronation day at Westminster Abbey on 28 June 1838. She wears coronation robes and the Imperial State Crown, carries the sceptre and the cross, and is seated in her homage chair.13 Following an established artistic tradition of constructing and disseminating the image of an emblematic British ruler, this portrait was the subject of numerous autograph copies, some of which were sent to British diplomatic missions abroad.14 A note drawn up after Hayter’s death in 1871 indicates that the state portraits made between 1859 and 1863 were sent to India, China, Turkey, Japan, Austria, Russia, and Iran.15 Four of these copies are still in the Government Art Collection and on display in the countries they were originally sent to.16 While these copies and their purpose are yet to receive further critical attention and assessment, the late art historian and surveyor of the Queen’s pictures, Sir Oliver Millar, noted that a number of documents in the National Archives reference these works, allowing a partial reconstruction of their history and their respective destinations (I, 106). Despite never having travelled outside Europe, Victoria’s presence was palpable internationally through the global dissemination of her image. She was aware of the potential impact of her portraits and that their circulation and display would serve both as a symbolic substitute for her presence and an indication of Britain’s political sphere of influence and international engagements throughout her reign.17 Hayter’s autograph copy that was intended specifically for the new British legation building in Tehran (completed in 1876) has been on continuous display ever since.18 The unique feature of this painting is that at the bottom left is an inscription in Persian which translates as: ‘Artwork made by George Hayter 1863. Holder of the Order of the Lion and the Sun’ (Fig. 3).19

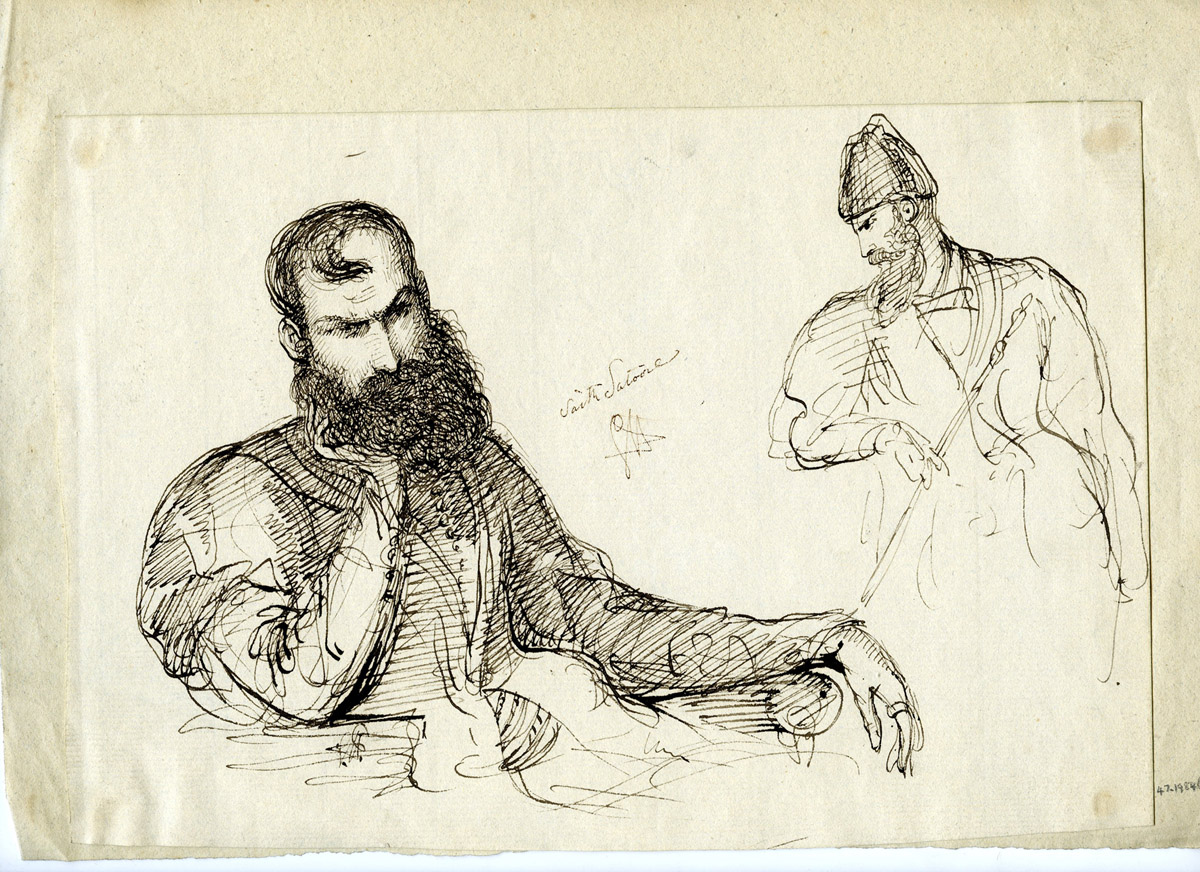

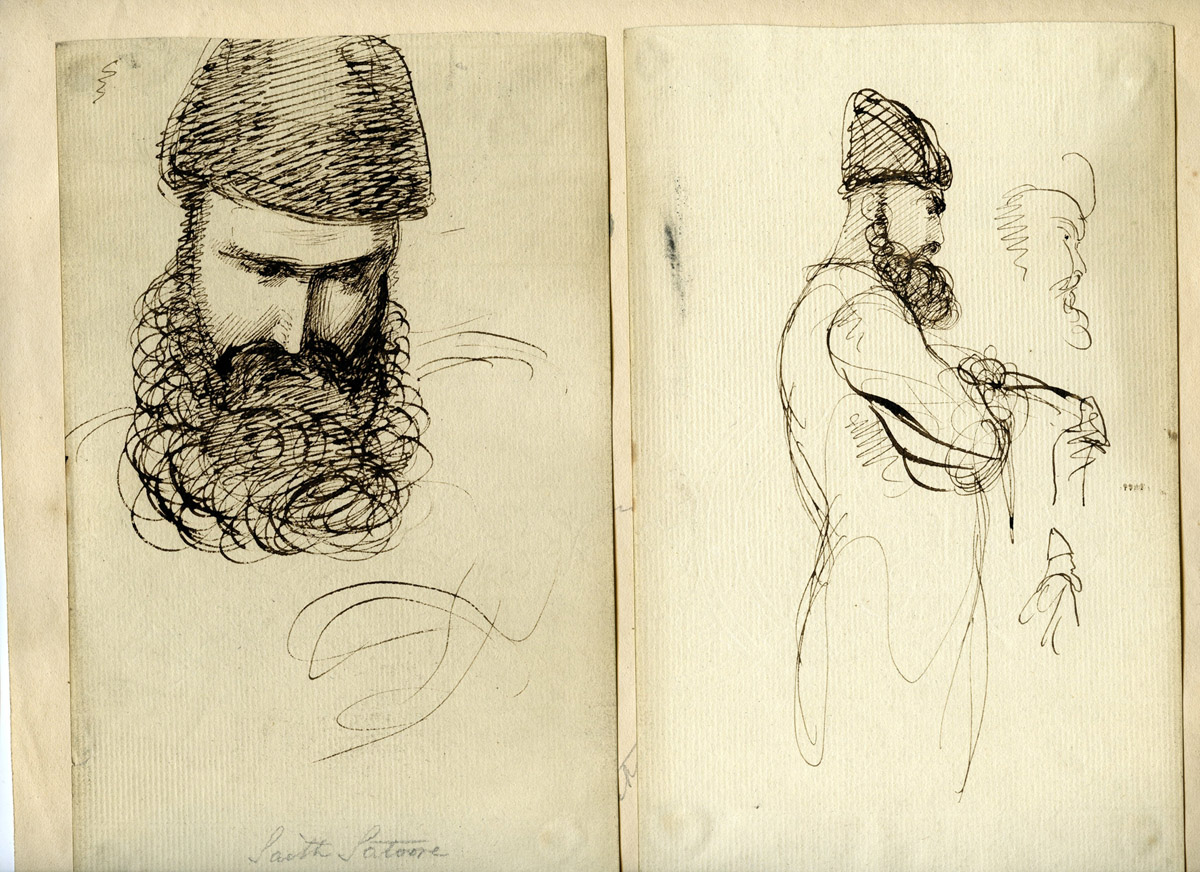

This imperial order was established by the second Qajar ruler, Fath ’Ali Shah (1722–1834) in 1808 and was usually conferred on foreign officials who distinguished themselves through their services to Persia.20 Given this prerequisite, it is necessary to clarify the circumstances in which Hayter came by this honour and to establish why a Persian inscription featured on a British royal portrait. It was Sir Denis Wright, the British ambassador to Tehran from 1963 to 1971, who first signalled the presence of the inscription as an exception to Hayter’s usual practice. He was curious about the reference to the noble order because, as he noted, ‘Hayter neither visited Iran nor painted any portraits of Iranian royalty.’21 However, Christie’s catalogue compiled for the studio sale in April 1871, following the death of the artist, reveals compelling evidence that Hayter had taken a great interest in Iran, both as an artist and as a collector.22 For example, among the lots offered for sale were a number of sketches titled The Shah of Persia Defending Himself against Brigands, and Two Persians Carrying away Circassian Women (today known as Banditti of Kurdistan Assisting Georgians in Surprising and Carrying off Circassian Women), as well as three silk Persian coats, an Astrakhan cap, two Persian cloths embroidered with gold lace, and a Persian dagger (lots 663, 688, 689, 692). More relevant to our purposes is lot 628, Heads of Three Persians, identified as an oil sketch signed by Hayter and dated 1831, which is now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (Fig. 4). As indicated by Hayter through an inscription underneath the portrait, the sitters are one Saith Satoor and Ali Hassan Bey. Satoor, a bearded figure wearing an Astrakhan hat, is depicted twice, once in full face and again in profile. Before its acquisition by the Victoria and Albert Museum, the work was owned by Rodney Searight, a director at the petrochemical company Shell and a notable twentieth-century collector of Middle Eastern art.23 The Searight Archive includes the collector’s notes on Hayter’s sketch, which reveals his unsuccessful attempts at unearthing evidence about how the painter came by his decoration, as well as references to two earlier sketches by Hayter, showing the same bearded sitter, which are now in the collection of the Museum and Art Gallery, Bolton, Lancashire. These sketches, made between 1824 and 1826, are part of an album of pen and ink drawings by Hayter and show Saith Satoor seated with the artist at his easel, on horseback, and either in profile or full face (Figs. 5, 6).24 The latter appears to be a preparatory sketch for Satoor’s portrait in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

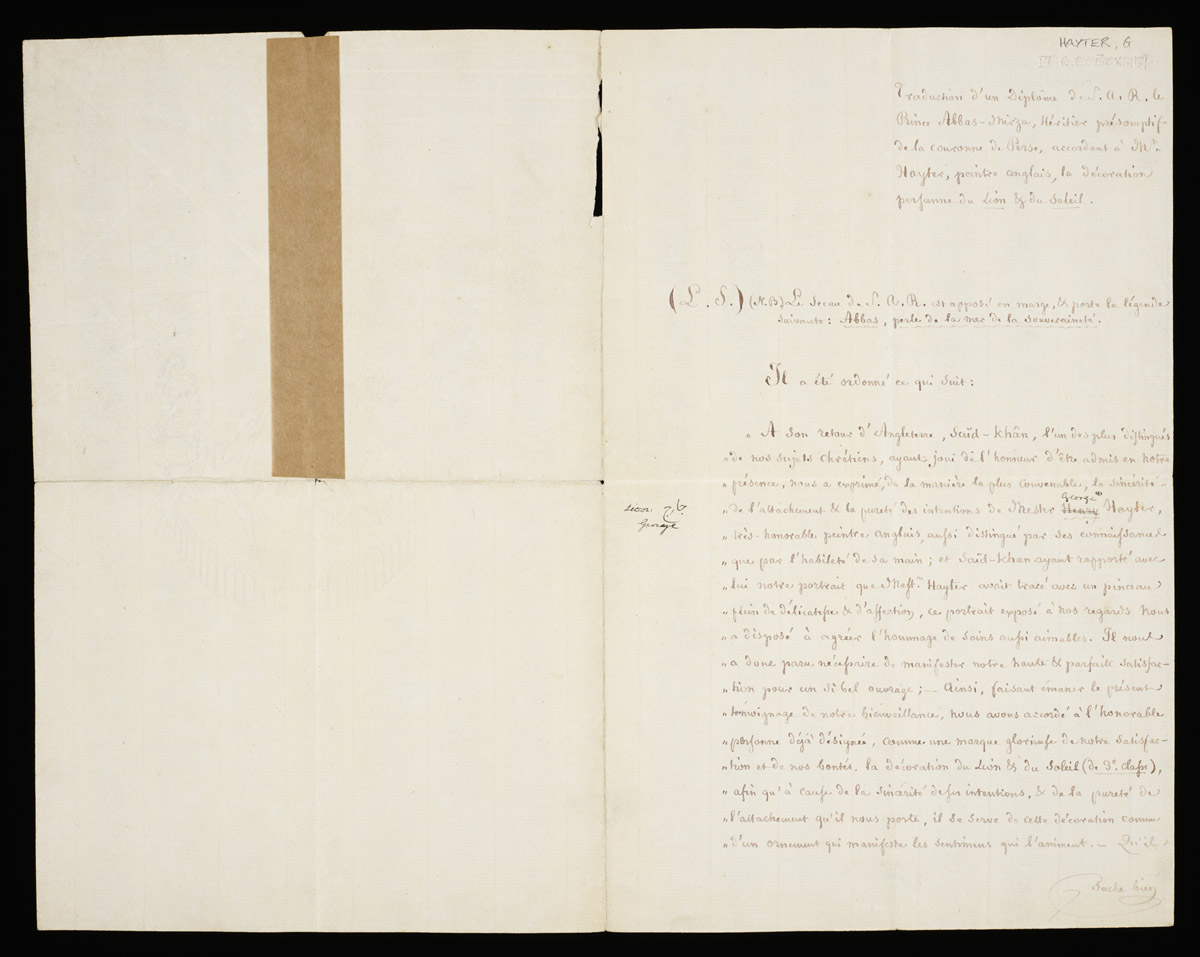

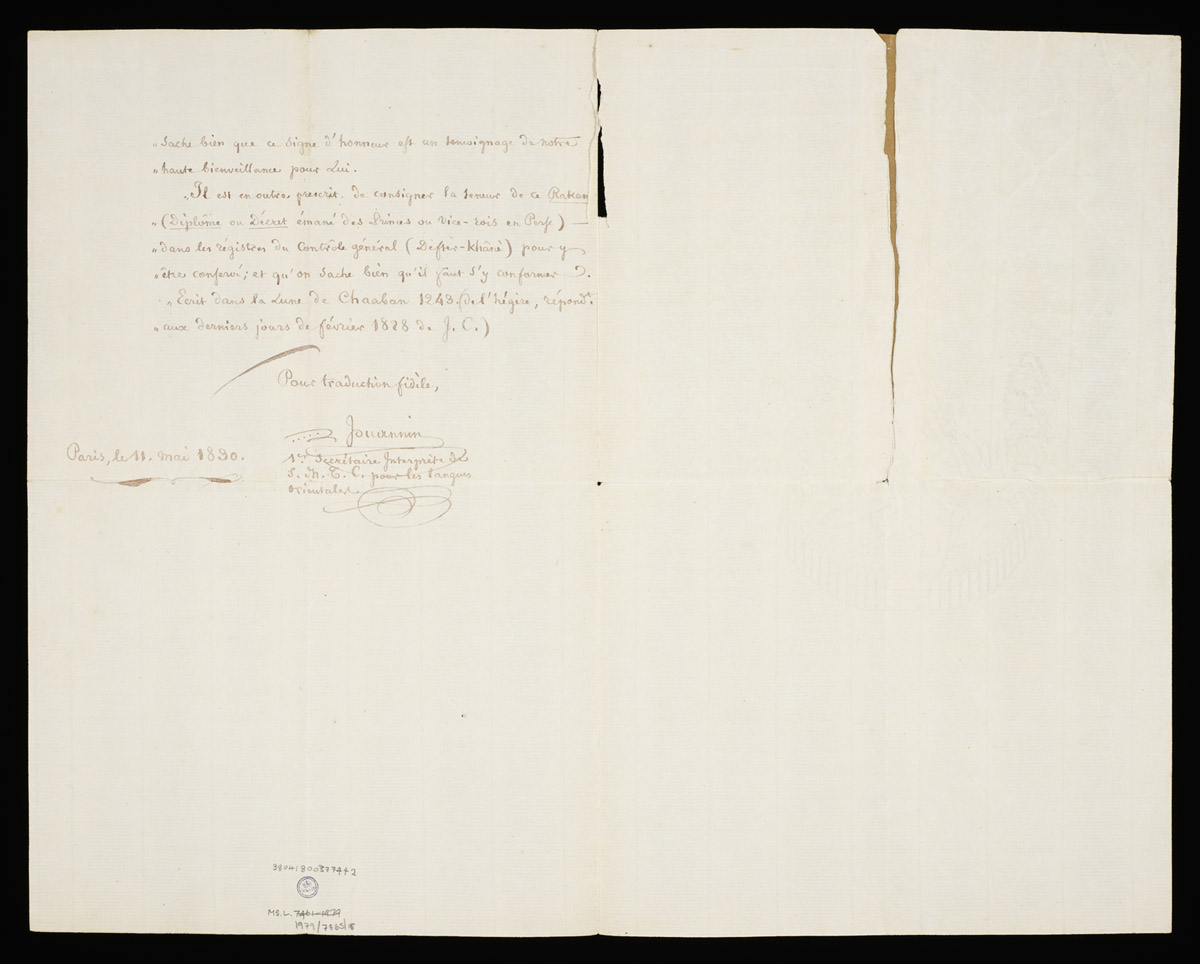

Saith Satoor, also known as Sedak Beg or Said Khan, was the son of an Armenian trader from Bushire and was educated in Bombay. He was a protégé of Abbas Mirza (1789–1833), the Qajar crown prince of Persia. From 1818 to 1819 Saith Satoor travelled with the Scottish painter and diplomat Sir Robert Ker Porter in Turkey, Iraq, and Iran.25 In his diary Ker Porter recounted that Abbas Mirza ‘provided me with a young Persian, called Sedak, of uncommon natural endowments, and still rarer advantages of education, to be with me constantly, as my interpreter.’26 From 1820 to 1835 Satoor was engaged in commercial enterprises between London, Turkey, and Iran, and it was on his recommendation that Hayter received the Persian decoration.27 The National Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Museum holds a French translation of the original Persian documentation — termed a firman — which accompanied the order and indicates that it was bestowed by Abbas Mirza upon George Hayter in February 1828 (Figs. 7, 8). The translation made in 1830 by Joseph Marie Jouannin, first secretary and interpreter to the French king for Oriental languages, reads:

On his return from England, Said Khan one of our most distinguished Christian subjects, conveyed the most sincere attachment and purity of intentions of Mr George Hayter, most honourable English painter, distinguished both for his knowledge and skill; Said Khan brought with him our portrait which Mr Hayter painted most delicately and with affection. By having this portrait displayed before our eyes, it made us approve of such a great homage. It therefore seemed necessary to manifest our great satisfaction for such a beautiful work by presenting him a testimony of our benevolence. As a glorious mark of our satisfaction and kindness, we offer the honourable gentleman, the decoration of the Lion and the Sun.28

In two self-portraits Hayter depicted himself wearing his Persian decoration and was evidently proud of it.29 On 30 August 1851 he recorded in his diary, ‘Called on the Persian Ambassador, showed him my Firman from Abbas Mirza, as a knight of the Sun and Lion.’30 Furthermore, in a letter dated 1852, Melkum Khan, the first secretary to the Persian Embassy in London, informed Hayter that, upon reading the firman from Abbas Mirza, the new Qajar emperor Nasser al-din Shah (1831–1896) had asked him to paint his state portrait.31

It is important to note that during the nineteenth century it was more common for foreign diplomats to be honoured with this order, so the fact that Hayter received it for his artistic achievements must have constituted an exceptional recognition of his talent. Moreover, Hayter was the only British portrait painter to have been presented with this order and it is noteworthy that he received it even before he was appointed principal painter in ordinary to Victoria.32 Therefore, the presence of the Persian inscription on the portrait of Queen Victoria should be read in multiple ways. Firstly, it was meant to impress his audience, the official and diplomatic community in Tehran. The British diplomats and their guests at the legation would have understood the inscription and appreciated the prestige of the award. Secondly, having a portrait of the reigning monarch on display in any British embassy of the late Victorian period, then as now, was something that would be expected. An inscription on the portrait in the local language was a sign of respect for the host country and would have reinforced diplomatic ties.

Although there is no evidence that Hayter had any knowledge of Persian, he could have either copied the text directly from the original firman or asked for help with a translation. It was not uncommon for him to call upon diplomats for this sort of assistance. On 19 April 1856, for instance, he called on the Turkish ambassador to sketch for him the crescent and star for a Peace Medal.33 Hayter corresponded regularly with representatives of the Persian Embassy in London, especially with Melkum Khan with whom he had ‘tea with lemon and smoked cigars of Persian tobacco’.34 Hayter could have enlisted his help during one of their encounters. While the Persian inscription on the portrait of Queen Victoria, and Hayter’s strong connections with the Iranian diplomatic circles, may seem sufficient as a justification for the presence of the portrait at the British Embassy in Tehran today, it is essential, nonetheless, to understand the wider context in which this portrait was placed there.35

In 1863, the date of Hayter’s portrait, Iranian officials and the director of the Persian Telegraph Service, Robert Murdoch Smith, signed the first Telegraph Convention, which would link the land telegraph systems of Europe and India by a line through Iran.36 With the new infrastructure in place, Murdoch Smith, followed by Lieutenant Henry Pierson, oversaw the shipment of the equipment needed for a new British legation building in Tehran, a necessary move given the continuing expansion of the old city and the dilapidated state of the first legation building.37 Balancing practical requirements with a desire to impress, James Wild proposed an Indo-Saracenic design for the new embassy building that would incorporate Mughal, Persian, Gothic, and classical elements (Stourton, pp. 88–103). Upon completion, it was regarded as ‘the finest of all the legation enclosures. The reception rooms and hall of the minister’s residence are very handsome and a byzantine clock tower gives the building a striking air of distinction.’38 Wild’s intricate design for the vault in the central hall and the interlacing ornamentation were integrated with the royal coat of arms and the gilded Latin initials: VR [Victoria Regina].39 For the decoration of the State Room, Caspar Clarke proposed a neoclassical template. It was in this room that Hayter’s portrait would be displayed. The Foreign Office papers inform us that he had received £210 for the portrait and that the cost of the frame was £60 (Millar, I, 106). On Hayter’s death in 1871 his son Angelo announced to the Foreign Office that there was a state portrait ordered for Persia, and paid for, remaining in the studio. This suggests that the portrait was sent to Tehran after 1871 but before 1876, when the new legation building was finished. The painting would have travelled in its frame, which was originally constructed with a view to protect it on the long overland journey from the Persian Gulf. Frames of this period would typically use gesso ornamentation. However, the gesso would have been too fragile in this instance, and it was decided that this frame would be fully carved in relief.40

It was around this time, in 1873, that Nasser al-din Shah also undertook the first of his three European grand tours as part of an exercise to raise Iran’s international profile and to attract investors. He was the first modern Iranian monarch to visit England, which he reached on 19 June. During his eighteen days in the country, he admired Buckingham Palace with its ‘peacocks, and a crane […] walking about on the lawn’; he marvelled at the sea lions and acrobatic monkeys at London Zoo, and strolled through a ‘very cloudy and foggy’ Hyde Park.41 He went to the theatre one evening to hear performances by Adelina Patti, an Italian soprano greatly admired by Giuseppe Verdi, and Emma Albani, the first Canadian soprano to become an international star, a favourite of Victoria’s (Diary, p. 158). What could have been more flattering for an Iranian ruler than to hear the opening aria from Handel’s opera Xerxes, ‘Ombra mai fù’, in which the great ancient Persian king of the Achaemenid Empire admires the tender and sweet shadow of a plane tree? Another memorable event was a state banquet held by the Lord Mayor at the Guildhall where the Shah feasted on salmon, lamb cutlets with peas, salad, pineapple compote, jellies, and cakes (pp. 151–55).

The Shah was also received at Windsor Castle by Queen Victoria and recounted in his diary this encounter depicted in a watercolour (1874) by Nicholas Chevalier:

Her most Exalted Majesty the Sovereign advanced to meet us at the foot of the staircase. We got down, took her hand, gave our arm, went up stairs, passed through pretty rooms and corridors hung with beautiful portraits, and entering a private apartment, took our seat. (p. 147)

The Queen endeavoured to make a lasting impression on Nasser al-din Shah: ‘The age of the Sovereign is fifty, but she looks no more than forty. She is very cheerful and pleasant of countenance’ (p. 151).

During their imperial encounter, the Shah was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Garter while the Queen received from him the Order of the Sun created especially for her. The Shah noted in his diary: ‘I too presented to the English Sovereign the “Order of the Sun,” set in diamonds, with its ribbon, and also the Order of my own Portrait’ (p. 149). Queen Victoria chose to wear it when she became Empress of India in 1876, a moment considered by John Plunkett to embody the ‘imperial reinvention of the monarchy’.42

It is in this context that we should revisit Hayter’s autograph portrait of Victoria, its intended location for display in the nineteenth century, and the wider story of diplomatic relations between the two countries. If the portrait initially represented cordial diplomatic relations, in time Victoria’s presence came to stand for a more complex and troubled relationship between Iran and British imperial power. While Iran was never part of the British Empire, it was used as a buffer state to protect British-ruled India from Russian expansionism during the nineteenth century. The empire and its slow end in the twentieth century casts a long shadow during which Victoria’s portrait has remained a silent witness at the embassy. The Tehran Conference in 1943 is an emblematic moment to reflect upon Britain’s changing status and a pivotal moment for relations between Britain and Iran. Anticipating the end of World War II, Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Joseph Stalin met in Iran to plan the shape of the post-war world. In his memoirs Churchill described his sixty-ninth birthday at the British legation as

a memorable occasion in my life. On my right sat the President of the United States, on my left the master of Russia. Together we controlled practically all naval and three quarters of all air forces in the world, and directed armies of nearly 20 millions of men, engaged in the most terrible of wars that had yet occurred in human history.43

Churchill’s birthday was celebrated at the British legation, but Roosevelt stayed at the nearby Russian Embassy where negotiations occurred. Churchill’s daughter Mary also attended the conference and spoke of her father as ‘the odd man out’.44

For generations before the conference, Britain wielded great military and economic power, and this is where Hayter’s coronation portrait of Victoria is rooted. After the conference, Britain’s power diminished. Tehran was among the last occasions that Britain sat on equal terms with the two rising powers. More recently, flashpoints between the countries have occurred around regime change, commercial control of Iranian oil, the 1979 Revolution, and the fatwa for blasphemy pronounced on Salman Rushdie in 1989 for publishing The Satanic Verses.45 As we have seen, this came to a head in the 2011 attack on the embassy and Victoria as a persistent image of British power.

In the wake of this turbulent period and the reopening of the embassy in 2016, the restored paintings had to be rehung. The display had to address the position of Victoria both literally and symbolically, reinstating her in the embassy while acknowledging this longer, difficult history of Anglo-Iranian relations. It was important that any new display of works of art embraced both the longevity of the relationship but also the difficulty inherent in that relationship. At the same time it illustrates a curatorial responsibility to preserve and recount shared stories and explore their complexities through art.46 While it seemed natural to reinstate the original hang based on historical photographs from the early 1930s, it was essential to allow space for a more in-depth exploration of the relationship between the two countries by introducing new works of art and raising new questions about the efficacy of art to create soft power.47 By tradition, the portraits of Queen Victoria and Fath ’Ali Shah were hung at opposite ends of an enfilade of four representational rooms: the Dining Room, the Breakfast Room, the Drawing Room, and the Fath ’Ali Shah Room. In 2011 the only other two works on display in the Dining Room apart from Victoria were the portraits of Edward VII and George V after Sir Samuel Luke Fildes. This reflected a narrow view of Anglo-Iranian relations, covering a particular period of British ascendancy, and an exclusively royal one, within a modern Islamic republic.

The first curatorial decision was to gather the images of Victoria and her immediate descendants in the Dining Room, including reinstating a portrait of Mary of Teck that had previously been hung there. This arrangement served to illuminate that particular imperial passage of British royal history into a single space and strengthened the associations with the Tehran Conference where these portraits provided a backdrop to the talks (Fig. 9).48

Continuing the theme of hosting as part of the ceremonial process in diplomacy, two paintings of Qajar entertainers were chosen for the Drawing Room (Figs. 10, 11).49 These works confer a playful note to the display and introduce a familiar sight in a domestic interior during the Qajar period, with the activities one might expect of a nineteenth-century gathering of women at court: dancing, playing music, smoking, and drinking tea.50 They also guide the visitors along an imaginary journey of rituals at the Qajar court and prepare them for a majestic encounter. Gradually approaching the next room, one has the impression of entering a presence chamber. Set against a deep yellow background, echoing the golden tiles of Golestan Palace, the Qajar residence in Tehran, Fath ’Ali Shah is poised to receive his visitors (Fig. 12).51 Seeing Ahmad’s regal portrait offers a similar experience to that described by Robert Ker Porter when he encountered and drew the Qajar ruler during a public audience in 1818:

He was one blaze of jewels, which literally dazzled the sight on first looking at him; but the details of the dress were these: A lofty tiara of three elevations was on his head, which shape appears to have been long peculiar to the crown of the Great King. It was entirely composed of thickly-set diamonds, pearls, rubies, and emeralds so exquisitely disposed, as to form a mixture of the most beautiful colours, in the brilliant light reflected from its surface. Several black feathers, like the heron-plume were intermixed with the resplendent aigrettes of this truly imperial diadem, whose bending points were finished with pear-formed pearls, of an immense size. His vesture was of gold tissue, nearly covered with a similar disposition of jewellery; and, crossing the shoulders, were two strings of pearls, probably the largest in the world. I call his dress a vesture, because it sat close to his person, from the neck to the bottom of the waist, showing a shape as noble as his air. (I, 325)

An embassy building is a space for diplomatic encounters, where displays of art can embody narratives about the past, present, and future. The Fath ’Ali Shah Room recreates encounters and diplomatic gift exchanges from the early modern period when Iran was at the heart of interactions between cultures, and European missionaries, artists, merchants, and curious travellers began to circulate, explore, and trade with Safavid Iran.

In 1626 Charles I sent a first embassy led by Dodmore Cotton to the court of Shah Abbas I in Isfahan to negotiate the opening of the silk trade.52 Two portraits in the Fath ’Ali Shah Room are a reminder of this early transitory diplomatic engagement: a print showing English traveller and adventurer Robert Shirley wearing his robe of honour received from Shah Abbas, and a seventeenth-century painted portrait of Thomas Herbert, courtier and historian to Charles I who was part of Cotton’s envoy.53

A more permanent British diplomatic presence in Iran started to take shape in the nineteenth century, when King George III appointed Sir Gore Ouseley as the first resident British ambassador to the court of Fath ’Ali Shah in 1810.54 On arrival in the new Qajar capital, Tehran, Ouseley established a base to encourage British diplomacy and new delegations began to arrive, often accompanied by artists. One of them was Robert Ker Porter who had the rare distinction of painting both George III and Fath ’Ali Shah. As depicted by Ker Porter, George III is represented in the display through a painting en grisaille.55 Although the two rulers never met in life and communicated only through diplomatic exchanges conveyed by their respective ambassadors, their portraits in the British residence in Tehran weave together the diplomatic story of Britain and Iran of the period.56

A final reminder of the diplomatic encounter that took place between Queen Victoria and Nasser al-din Shah in London in 1873 is suggested through an invisible axis that connects Hayter’s portrait of Victoria in the Dining Room to a painting by Nasser al-din Shah in the Fath ’Ali Shah Room (Fig. 13). Just like Hayter’s painting, that by the Shah features a Persian inscription, which translates as follows: ‘A view of the city of Venice in Italy. Painted in oil colours on canvas by me from a small watercolour picture. In the year 1274 [1857–58] at Tehran. Nasir ud din Shah Qajar.’57

Viewed together as a coherent display, these works begin to tell multiple stories of diplomatic engagements and exchanges, recreating a sense of the historical interactions between representatives and agents of both countries. While they evoke narratives of the past, displays are also about the present and the future. To balance and complement the historical hang, modern and contemporary works were introduced in the Study Room. Among them are a series of prints by Derek Hirst, titled Paradox (1975), that drew inspiration from the architectural motifs found in the interior of the celebrated Jameh Mosque of Isfahan.58 Also on display are the Round Dance series by Shirazeh Houshiary, an artist whose work combines elements derived from Iranian culture and Western art traditions. Her etchings intricately and densely overlay Islamic calligraphy on illegible abstraction to describe an indivisible universality. Each of the images are inspired by the poems of Jajal al-Din al-Rumi, the thirteenth-century poet, scholar, and mystic who influenced the spiritual philosophy of Sufism.59 Houshiary was born in Shiraz, Iran, in 1955 and moved to London in 1973, a migration of talent in itself a manifestation of soft power. Displaying her works in the same building as Hayter’s portrait sends a powerful message about changes in British society and its geopolitical role.

Each of the works selected for the newly curated display speak in a respectful way to a cultural encounter that extended long before and long after the reign of Queen Victoria. Her portrait is a relic of an imperial past, yet when placed within the wider context of an enduring political and diplomatic relationship, it still has value today. Portraits of powerful women remain uncommon in Iran, then as now.

Victoria has changed, and not just physically. Attacked as a symbol of imperial power, her restoration and return as part of a renewal of diplomatic ties carries a hopeful symbolism. Diplomacy is not merely transactional. It also hinges on personal relationships and trust between diplomats and their interlocutors. Art can speak directly to us to tell stories, to start conversations, and to build trust. Nobody reading this article would want Victoria’s portrait to be violently attacked as it was in 2011, and yet in the scars it has allowed new tales to be told (Fig. 14).

Notes

- Reports on the attack and its immediate aftermath, with photographs and video footage of the extent of the damage to the interior of the building and a number of the works of art were released by news agencies around the world. See Robin Pomeroy, ‘Iranian Protesters Storm British Diplomatic Compounds’, Reuters, 29 November 2011 <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-britain-embassy-idUSTRE7AS0X720111129>; ‘Iran Protesters Storm UK Embassy in Tehran’, BBC News, 29 November 2011 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-15936213>; and Robert F. Worth and Rick Gladstone, ‘Iranian Protesters Attack British Embassy’, New York Times, 29 November 2011 <https://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/30/world/middleeast/tehran-protesters-storm-british-embassy.html> [all accessed 27 November 2021]. [^]

- We thank our colleagues at the Government Art Collection and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport for all the support they showed us while we undertook this extensive research and curatorial project. Spanning from the sixteenth century through to the present day, the UK Government Art Collection is the most widely distributed collection of British art in the world and is viewed by thousands of visitors each year. For more information on the history and role of the Government Art Collection, see Penny Johnson and others, Art, Power, Diplomacy: Government Art Collection: The Untold Story (London: Scala, 2011). [^]

- The portrait of George V after Sir Samuel Luke Fildes was completely destroyed. The last visual record of this painting still intact is a press photograph showing it out of its frame and leaning upside down against the British Embassy compound wall <https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/976/mcs/media/images/57051000/jpg/_57051857_013417150-1.jpg> [accessed 27 November 2021]. [^]

- The image of the damaged portrait of Queen Victoria was shown on Newsnight, BBC2, 2 December 2011, 10.30pm. [^]

- We are grateful to Dominick Chilcott, Her Majesty’s Ambassador to Iran in 2011, for recounting his experience of the attack in an interview as part of episode 3 of A Meeting of Cultures podcast. This series presented by Dr Laura-Maria Popoviciu marks the new installation of works of art at the British ambassador’s residence in Tehran. The podcasts evoke the story of the long relationship between the two countries through works of art from the collection and through conversations with curators, academics, diplomats, and architects. The web page also includes three conservation videos of Qajar paintings which were part of the new display. Laura-Maria Popoviciu, A Meeting of Cultures, series of podcasts and videos, Government Art Collection, 2019 <https://artcollection.culture.gov.uk/stories/a-meeting-of-cultures/> [accessed 27 November 2021]. [^]

- We are grateful to Nicholas Hopton, Her Majesty’s Ambassador to Iran between 2017 and 2018, for his support in facilitating the repatriation of the artworks to the UK. [^]

- We thank Jim Dimond for his work in restoring the painting. [^]

- On the history of British-Iranian diplomatic relations since the late eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century, see Denis Wright, The English amongst the Persians during the Qajar Period, 1787–1921 (London: Heinemann, 1977); and Anglo-Iranian Relations since 1800, ed. by Vanessa Martin (London: Routledge, 2005). [^]

- Anny Shaw, ‘Queen Victoria and Fath-Ali Shah portraits torn apart in 2011 British Embassy attack, to go back on show in Tehran’, Art Newspaper, 29 November 2018 <https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2018/11/29/queen-victoria-and-fath-ali-shah-portraits-torn-apart-in-2011-british-embassy-attack-to-go-back-on-show-in-tehran> [accessed 27 November 2021]. [^]

- Jennifer Scott, The Royal Portrait: Image and Impact (London: Royal Collection Enterprises, 2010), p. 138. [^]

- London, National Portrait Gallery, Heinz Archive and Library, A. Hayter, ‘Diary of Sir George Hayter, 1st January 1838–21st June 1858’, transcript 9 August 1857, pp. 209–10, NPG106287, HAYTER (G). A2. [^]

- Queen Victoria’s Journal, 12 November 1847 and 20 March 1839 <www.queenvictoriasjournals.org> [accessed 27 November 2021]. [^]

- For a description of the coronation ceremony and the appearance of Queen Victoria on the day, see Aimeé Stagl and Günter Fahrnberger, ‘Queen Victoria — Icon of Victorian Age and Feminism’, International Journal of Advanced Multidisciplinary Research and Studies, 2016, 1–10. [^]

- On the question of royal image making and its purpose, see Scott; and David Howarth, Images of Rule: Art and Politics in the English Renaissance 1485–1649 (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997). Hayter’s state portrait of Queen Victoria was also engraved by royal engraver Henry Thomas Ryall and circulated worldwide to announce her reign. [^]

- Kew, National Archives, Records of the Lord Chamberlain and other officers of the Royal Household, LC 1/756, II, 5. [^]

- Queen Victoria commissioned from Hayter a version of the state portrait for the British Embassy in Paris in August 1840. The painting now on display in the British ambassador’s residence in Paris was the version originally sent to the British Embassy in Vienna, where it remained until 1946; it was only sent to Paris in 1982. It was at some stage cut down on all sides and is hence smaller than the original. Another version, originally sent to St Petersburg, is now in the British Embassy in Moscow. The version which arrived in Peking (Beijing) in July 1861 was destroyed by fire in 1967, when the chancellery and residence of the British chargé d’affaires burnt down. See Oliver Millar, The Victorian Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), I, 105–06. [^]

- For instance, Queen Victoria ensured that a copy of her state portrait by Hayter was sent to be displayed in the British Embassy in Paris and not Wilkie’s version of the portrait (Scott, p. 138). [^]

- For an account of the history of the British ambassador’s residence building in Tehran, see James Stourton, British Embassies: Their Diplomatic and Architectural History (London: Lincoln, 2017), pp. 88–103. [^]

- We are grateful to Sarah Piram, the Iran Heritage Foundation Curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, for her help in transcribing and translating the inscription. [^]

- See Sir Denis Wright, ‘Sir John Malcolm and the Order of the Lion and Sun’, Iran, 17 (1979), 135–41. For an example of the Order of the Lion and the Sun, see this insignia by Muhammad Ja’far from 1826–27 in the Victoria and Albert Museum <https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1270287/insignia-of-the-muhammad-jafar/> [accessed 27 November 2021]. [^]

- Britain and Iran, 1790–1980: Collected Essays of Sir Denis Wright, ed. by Sarah Searight (London: Iran Society, 2003), p. 15. [^]

- Christie, Manson & Woods, Catalogue of the Remaining Pictures and Original Sketches in Oil, Pen, and Chalk, and the Collection of Old Pictures & Engravings of the Late Sir George Hayter, M.a.s.l., Principal Painter in Ordinary to Her Majesty; Including Several Grand Finished Works, Many Portraits Made for the Picture of the House of Commons (London: [no. pub.], 1871). [^]

- See the Rodney Searight file in the Searight Archive, Prints, Drawings and Paintings Department, Victoria and Albert Museum, London. [^]

- We are grateful to Matthew Watson, museum access officer at Bolton Museum for sending us images of these sketches and for providing further information about the Hayter album in the collection. It is possible that this album was part of the objects sold at the artist’s studio sale in 1871. [^]

- Robert Ker Porter accompanied Sir Gore Ouseley, the first resident British ambassador, to Iran in 1811. As an artist to Ouseley’s embassy, Ker Porter made drawings and documented the journey. [^]

- Sir Robert Ker Porter, Travels in Georgia, Armenia and Persia, Ancient Babylonia […] during the years 1817, 1818, 1819 and 1820, 2 vols (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown 1821–22), I (1821), pp. 251–52; and ‘Diary of Sir George Hayter’, transcript 2 March 1854, p. 175. [^]

- Saith Satoor was involved in a misunderstanding when attending a meeting of the British and Foreign School Society at the Freemason’s Tavern with the Duke of Sussex, when he was mistaken as the Persian ambassador: ‘In the first place he is not the Persian Ambassador, in the second place he is not a Persian minister, and in the third place he is no more a Persian than is the Editor of the Literary Humbug, but an Armenian who came to England with the Persian Ambassador, but with whom he is not at present on terms of the best intimacy. He filled the honourable and high capacity of servant, for fourteen years, to Dr. Campbell, the Rev. Mr. Canning, Colonel D’Arcy, and to several other gentlemen.’ See ‘Humbug Extraordinary, or the Duke of Sussex Deceived’, Literary Humbug, 18 June 1823, p. 92, emphases in original. Satoor also acted as a translator for British artist William Page when he visited Turkey in the 1820s as part of the William Campbell/Lady Ruthven party. An 1821 watercolour by Page showing Saith Satoor dressed in a green Persian dress, with a Persian dagger and an Astrakhan cap was recorded with Guy Peppiatt Fine Art in 2019. See ‘Portrait of Saith Satoor Sadik Beg’, British Drawings and Watercolours 2019, catalogue (London: Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, 2019) <http://www.peppiattfineart.co.uk/cat/Peppiatt_Drawings_2019_catalogue.pdf> [accessed 27 November 2021] (item no. 32, p. 38). [^]

- London, National Art Library, Diploma translated into French, awarded to George Hayter by Abbas-Mirza, Prince of the Qajars, MSL/1979/7865/15. Authors’ translation from French. To this date, we have not been able to identify Hayter’s portrait of Abbas Mirza. [^]

- The self-portraits made in 1843 and 1863 are both held in private collections. [^]

- ‘Diary of Sir George Hayter’, transcript 30 September 1851, p. 4. The Persian ambassador also made an impromptu visit to his studio in 1851. [^]

- ‘Diary of Sir George Hayter’, transcript November 1852, p. 168. The same account states that two years later, a certain Mr Reed left London for Tehran, carrying with him Hayter’s portrait of the Shah. See transcript 25 March 1854, p. 176. [^]

- Robert Ker Porter also received this decoration from Fath ’Ali Shah. However, his achievements were recognized as part of a diplomatic mission: he was accompanying Sir Gore Ouseley’s convoy in an official capacity and documenting the journey. See R. D. Barnett, ‘Sir Robert Ker Porter — Regency Artist and Traveller’, Iran, 10 (1972), 19–24. [^]

- ‘Diary of Sir George Hayter’, transcript 19 April 1856, p. 198. Kostaki Musurus Paşa served as ambassador of the Ottoman Empire to London between 1851 and 1881. [^]

- ‘Diary of Sir George Hayter’, transcript 19 November 1852, p. 168. When Hayter became aware of the failed assassination attempt on Nasser al-din Shah in 1852, he called at the Persian Embassy in London to learn more about this incident for a sketch that he intended to make on it. Melkum Khan was said to have been ‘horror struck’ at Hayter’s idea and advised against Hayter making the sketch. However, Hayter, undeterred, completed the work, and it is listed in the Christie’s sale catalogue of Hayter’s possessions on his death. See ‘Diary of Sir George Hayter’, transcript 13 October 1852, p. 168; and Catalogue of the Remaining Pictures, lot 297. [^]

- During this period, Europe became increasingly aware of Iran through international exhibitions, including the Persian displays at the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in London in 1851. John Nash depicted Queen Victoria with Prince Albert standing outside the Persia pavilion in his print of the inauguration of the Great Exhibition. See ‘The Inauguration’, in Dickinson’s Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition, 2 vols (London: Dickinson, 1854), I, unpaginated. [^]

- See Jennifer M. Scarce, ‘Major General Sir Robert Murdoch Smith KCMG and Anglo-Iranian Relations in Art and Culture’, in Anglo-Iranian Relations, ed. by Martin, pp. 21–35. [^]

- See Hugh Arbuthnott, Terence Clark, and Richard Muir, British Missions around the Gulf, 1575–2005: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman (Folkestone: Global Oriental, 2008); and John Gurney, ‘Legations and Gardens, Sahibs and Their Subalterns’, Iran, 40 (2002), 203–32. [^]

- Isabella Bird, Journeys in Persia and Kurdistan, 2 vols (New York: Putnam’s Sons; London: Murray, 1891; repr. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), I, 188. [^]

- Moya Carey, ‘Master Builders: Owen Jones, Caspar Purdon Clarke and the Mirza Akbar Drawings’, in Persian Art: Collecting the Arts of Iran for the V&A (London: V&A Publishing, 2017), pp. 27–67. [^]

- To this day, the painting has been kept in its original frame. We thank Nao Ikeda for restoring the frame. [^]

- The Diary of H.M. The Shah of Persia during His Tour through Europe in A.D. 1873, ed. by J. W. Redhouse (London: Murray, 1874), pp. 143, 187. He would have encountered a similar sight in the garden of the British legation in Tehran: ‘The building opens by a verandah at the back on to a lovely garden, where swans float on brimming tanks of water and peacocks flash amid the flower-beds […]. The coolness and seclusion of the entire enclosure is one of the most agreeable and uncommon features in Teheran.’ See George N. Curzon, Persia and the Persian Question, 2 vols (London: Cass, 1966), I, 311. [^]

- John Plunkett, Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 10. [^]

- Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, 6 vols (London: Cassell, 1948–54), V: Closing the Ring (1952), p. 329. [^]

- Al Cimino, Roosevelt and Churchill: A Friendship that Saved the World (New York: Chartwell, 2018), p. 140. [^]

- Historical antipathy can also be revealed in unexpected ways. While most roads around the British Embassy compound are named after Persian poets, such as Ferdowsi (c. 935/940–1019/1026) or Hafez (1315–1390), one was provocatively renamed Bobby Sands in 1981 after the leader of an Irish Republican Army hunger strike, which resulted in the embassy deciding to relocate its entrance. Initially, the street was named after Winston Churchill. There is also a high wall on the opposite side of the street marking the edge of the compound of the Russian Embassy. The wall serves as another visual indicator and reminder of ‘the Great Game’ and the tensions between the political power blocs. See Firuz Kazemzadeh, Russia and Britain in Persia: Imperial Ambitions in Qajar Iran (London: Tauris, 2013). For a more complete history of the Persian Revolution, see E. G. Browne, The Persian Revolution of 1905–1909 (London: Cass, 1966). For a detailed chronology of the revolution, see Nicholas M. Nikazmerad, ‘A Chronological Survey of the Iranian Revolution’, Iranian Studies, 13 (1980), 327–68. See also, John C. Swan, ‘The Satanic Verses, the Fatwa, and Its Aftermath: A Review Article’, in Library Quarterly, 61 (1991), 429–43. [^]

- We thank Rob Macaire, Her Majesty’s Ambassador to Iran between 2018 and 2021, for all his support in reinstating the new display. [^]

- Soft power has been defined as the ability to influence the behaviour of others through attraction rather than coercion or payment. It is expressed through a country’s culture, its values, and international behaviour. Britain ranks consistently highly in soft power indices, despite the uncertainties of Brexit. In 2021 and 2020 the UK ranked third for soft power prowess. See Global Soft Power Index 2021 and 2020 <https://brandirectory.com/globalsoftpower/> [accessed 27 November 2021]. In Iran, however, despite efforts to implement this notion, soft power itself can be viewed with suspicion. See S. M. Mirmohammad Sadeghi and R. Hajimineh, ‘The Role of Iran’s “Soft Power” in Confronting Iranophobia’, MGIMO Review of International Relations, 12 (2019), 216–38 <https://doi.org/10.24833/2071-8160-2019-4-67-216-238>. [^]

- Photographs from the Tehran Conference album show Winston Churchill and his guests in the Dining Room on the occasion of his birthday. The portraits of the British royals, including that of Victoria, can be seen in the background. [^]

- These paintings were acquired by HM Government in 1926 from the collection of Count Thun, the previous owner of the British Embassy in Prague. We are grateful to Tim Stanley, senior curator in the Middle East Department of the Victoria and Albert Museum for signalling the research of Dr Iván Szántó (Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest) on Qajar paintings in Central-Eastern European collections and, in particular, his paper ‘Pearls of Persian Painting at Random Strung in Eastern Europe’, presented in 2018 at Musée Louvre-Lens as part of the conference ‘Révéler l’inédit: Regarder l’art Qajar au 21e siècle’. We thank Dr Szántó for providing further information on this topic and for making his research available to us. [^]

- Their subject matter is consistent with a large group of Iranian paintings showing women entertainers at the court. See Mounia Chekhab-Abudaya, Qajar Women: Images of Women in 19th-Century Iran (Milan: Silvana, 2016). Other examples in the Victoria and Albert Museum include paintings of women playing musical instruments, such as drums or tambourines, dancing, and holding wine decanters. See Sussan Babaie, ‘The Paintings that Turned Persian Art on Its Head in the 19th century’, Apollo, 2 June 2018 <https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-the-qajar-dynasty-turned-persian-art-on-its-head/> [accessed 27 November 2021]. [^]

- Ahmad’s painting of Fath ’Ali Shah is thought to have been a gift from the sitter to John Campbell, chargé d’affaires in Tehran between 1830 and 1835, and so the painting has an even longer association with the British mission than Victoria and predates the building in which it hangs. Fath ’Ali Shah was painted in 1832–33, just five years before Hayter’s prime portrait. For more information about Qajar royal paintings, see Royal Persian Paintings: The Qajar Epoch, 1785–1925, ed. by Layla S. Diba, with Maryam Ekhtiar (New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art in association with Tauris, 1998); and Gwenaëlle Fellinger and Carol Guillaume, L’Empire des roses: Chefs d’oeuvre de l’art persan du XIXe siècle (Lens: Louvre-Lens, 2018). [^]

- Sir Roger Stevens, ‘European Visitors to the Safavid Court’, Iranian Studies, 7 (1974), 421–57; and R. W. Ferrier, ‘The European Diplomacy of Shah Abbas I and the First Persian Embassy to England’, Iran, 11 (1973), 75–92. [^]

- The print of Shirley is after Sir Anthony Van Dyck’s portrait which is now in the National Trust Collection at Petworth House. Thomas Herbert was part of Cotton’s envoy and recounted his travel adventures in his journal, Some Yeares Travels into Divers Parts of Asia and Afrique which was published in London in 1638. The inscription in Welsh on Herbert’s portrait reads ‘Pawb Yn Yr Aver’. It represents the Herbert family motto and translates into English as ‘Each to their own custom’. It also appears on the title page of Herbert’s 1677 edition of Some Yeares Travels. See also G. Bernard Wood, ‘Cavalier of 17th-Century York’, Country Life, 29 November 1962, pp. 1359–61. [^]

- See James Morier, A Second Journey through Persia, Armenia, and Asia Minor, to Constantinople, between the Years 1810 and 1816 (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1818). [^]

- On 4 June 1799 the units of volunteers based in London were inspected by George III in Hyde Park as part of the King’s birthday celebrations. Cavalry and infantry corps were arranged on three sides of the park. The King entered the park gates at 9 a.m., accompanied by the Prince of Wales and the dukes of York, Kent, Cumberland, and Gloucester. The troops then manoeuvred past his majesty in line, under the direction of General Dundas. [^]

- In 1809 Persian ambassador Mirza Abul Hasan Khan Ilchi Shirazi set off for England to negotiate a treaty of alliance on behalf of Fath ’Ali Shah. See A Persian at the Court of King George 1809–10: The Journal of Mirza Abul Hassan Khan, ed. by Margaret Morris Cloake (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1988). [^]

- For a description of Nasser al-din Shah’s tour through Italy, see The Diary of H.M. The Shah of Persia pp. 295–362. Nasser al-din Shah’s fascination with photography is well known. He received two early photographic cameras from Queen Victoria and Tsar Nicholas I while he was the crown prince of Iran. He learned how to use these cameras and became an amateur photographer himself. See The Eye of the Shah: Qajar Court Photography and the Persian Past, ed. by Jennifer Y. Chi (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015). [^]

- Five screen prints from Derek Hirst’s Paradox series were selected for display in the Study Room. On Derek Hirst and his influences, see Robert Heller, Derek Hirst (London: Momentum, 2007). [^]

- Shirazeh Houshiary’s etchings from the Round Dance series made in 1992 were selected for the Study Room. See Shirazeh Houshiary, Dancing around My Ghost (London: Camden Arts Centre; Dublin: Douglas Hyde Gallery, 1993). [^]