The discrepancy is glaring. Surely, not even the most protracted version of the ‘long nineteenth century’ would stretch into the middle of the twentieth? And yet, the spectre of the Victorians, their ghostly, imagined forms and objects, was a powerful cultural presence in Britain at the end of the Second World War and its immediate aftermath. The Victorian age haunted post-war Britain in diverse ways; everywhere there were physical and material traces of homelessness, ruins, and poverty that belonged very decisively in the present but recalled the nineteenth-century past.

In the years following the end of the war, Britain faced an unprecedented task of post-war recovery and reconstruction. While this did not necessarily involve an aesthetics of modernization and the new, it is nevertheless the case that post-war planners imagined the future as a definitive and streamlined break with the look and values of the historical past; a symbolic step away from the darkness of the nineteenth century into the light and hope of the second half of the twentieth. Post-war Britain was surrounded by remnants of Victorianism and it was the role of modern planning to erase the visible signs of this decaying and corrupt past.

This attitude was most clearly articulated in William Beveridge’s proposed reforms to the existing system of philanthropic social welfare. The scheme, which was set out in Beveridge’s 1942 report titled ‘Social Insurance and Allied Services’, aimed to remedy social inequalities by introducing a comprehensive policy of social change and, most notably, a free national health service that would eradicate the five great evils that obstructed the road to progress and reconstruction: ‘want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness’.1 These are Victorian evils, materialized in the forms of the workhouse and the slum. The post-war narrative was a break with these Victorian values and the re-emergence of the nation as reconstructed and modern.

While a historical break or rupture appears to suggest an absolute termination of that which has come before, in fact, the image of the past, and especially of the recent past, becomes increasingly significant as that which must be rejected or repudiated in order to create the modern, the new society. Rather than an absence of the nineteenth century in post-war Britain, therefore, the Victorian is everywhere present and social and cultural continuities are emphatic. Cultural historian Frank Mort has described post-war Victorianism as

an eclectic and accretive version of the nineteenth-century past that was sufficiently composite to include images and environments from the Edwardian period as well. […] Such uses of history were not simply residual; the past was understood to be an active presence in the development of contemporary social and sexual relationships.2

Significantly, Mort refers specifically to the active role of the Victorian in defining post-war social and sexual identities. Not simply a deadened trace, Victorianism assumes different meanings and associations and actively participates in the creation of modern gender and sexual identities.

There is a deep ambivalence in post-war responses to the society and culture of Victorian Britain. At once a relic of physical, psychological, and social injustice that must be swept away by late twentieth-century modernization, it also generated its own distinctive fascination and beauty; its intensely experienced attractions, as well as its abominations. What follows is a consideration of the power of Victorian beauty in the decade following the end of the Second World War, from roughly 1945 to 1955. It does not examine the complex philosophies of Victorian aesthetics — this has been and should be left to others.3 Rather, it is an attempt to understand what Victorian beauty meant to Britain in the post-war years and what work Victorianism did for the nation in this period of recovery and redefinition. Taking its cue from a British period melodrama, made in 1945 and set in the late nineteenth century, it goes on to discuss post-war femininity and Victorian masquerade and other instances of the irresistible fascination of Victorian material culture. Dust and superstition; repression and sensuality; outmoded and time-honoured: the Victorian past was a beautiful, perplexing puzzle to the post-war present.

My title suggests two distinct periodizations — the Victorian and at the end of the Second World War — both of which can be and have been debated, accepted, and contested. It is, nevertheless, worth thinking about just how messy and porous these historical categories can be. Consider, for instance, someone born in 1875. At the end of the war, they would be seventy years of age and would have lived through the reigns of Victoria, Edward VII, George V, Edward VIII, and George VI, as well as two world wars. Is this person a Victorian, an Edwardian, or a new Elizabethan? Historical periodization does not sit comfortably with generational change and continuity, and cannot account for the experience of the present through memories of the historical past. I am reminded of the character of Mrs Wilberforce in The Ladykillers, a brilliant Ealing comedy, made in 1955 and directed by Alexander Mackendrick. Mrs Wilberforce is an elderly widow, who lives in a rickety house, next to King’s Cross station. The house and its owner are relics of past times; the rooms are cluttered with Victorian gewgaws and the tiny Mrs Wilberforce appears to have stepped out of the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. The plot follows a gang of criminals, posing as a string quartet, who rent rooms in her house in order to plan a robbery. They pull off the heist but are eventually thwarted by Mrs Wilberforce who ends up with the money. Mrs Wilberforce is played by the British actress, Katie Johnson (Fig. 1). Johnson was born in Sussex in 1878 and began her stage career in 1894; her first film role was in 1932 and she was seventy-seven when she starred in The Ladykillers. Katie Johnson/Mrs Wilberforce are post-war Victorians, embodiments of the extended reach of the nineteenth century into the social and cultural life of post-war Britain.

Ealing Studios suggested drawing on nostalgia for the Victorian age in the marketing of another of its films, a historical melodrama called Pink String and Sealing Wax (UK; dir. Robert Hamer), made just at the end of the war, in 1945, and set in Brighton in the 1880s. In its pressbook, produced to promote the film and to suggest commercial tie-ins for cinemas, it considered the appeal of the central characters to modern audiences:

To those of us who can remember the ending of the nineteenth century there is something penetratingly nostalgic about the life of the Sutton family. […] The streamlined twentieth century is exchanged for the lethargic top-heavy nineteenth.

Yesterday is today in embryo. The problems of the Sutton family, domestic life and young lives, are the problems of to-day.

There is, too, something grim about that period of luxury and poor sanitation, gaslight and horse-drawn carriages, something that makes Googie Withers’s clever portrayal of the flashy murderess […] more convincingly realistic than it would be in any other period.4

The pressbook makes a botch of defining the appeal of the film, suggesting that its Victorian setting is both nostalgic and convincingly realistic, different from and yet essentially connected to the contemporary moment. Quickly, it resorts to a mythical lexicon of Victorianism: poverty, gaslight, and dangerous women.

Googie Withers’s arresting portrayal of the ‘flashy murderess’ is at the dramatic heart of the film. A production still shows her in full length; the face and hair of a 1940s pin-up on the body of a late nineteenth-century mannequin. This is Victorian beauty, styled for 1945. Standing on a street corner, illuminated by the gaslight, she is bold, ornamental, daring. She recalls the Victorian period, while also clearly belonging to the end of the war. This is not a question of authenticity, of weighing up the period accuracy of her costume and appearance, but of understanding how one historical moment is imbricated in another, how an evocation of the Victorian works for British culture at this pivotal moment at the end of the war.

The film is based on a play of the same title by Roland Pertwee, which had its premiere at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London in September 1943.5 Made in the studio, during wartime, the film has a limited number of locations: a chemist’s shop; a Victorian parlour; a pub; and the streets immediately around these interiors. The drama is built on the clash of two Victorian worlds: a middle-class family, the Suttons, ruled by its unyielding paterfamilias, and the seedy underworld of a pub, inhabited by a drunken landlord and his beautiful wife, Pearl (Googie Withers). The film opens with a report on a murder trial in which the female defendant has been found guilty and sentenced to hang, largely on the evidence of Mr Sutton, a pharmacist and public analyst. We then see Sutton’s rigid and cruel behaviour to his children: refusing to allow David, his oldest son, to marry his sweetheart; denying his daughter a longed-for singing career; and telling his youngest girl that the guinea pigs that he has brought into the house are not a present but intended for his laboratory experiments.

Heartbroken and angry, David leaves the house and visits a pub, the Dolphin, on the Brighton seafront, run by a violent landlord and his wife, Pearl, who is having an affair with the local petty crook, Dan. David quickly becomes infatuated with Pearl and when he finds her with a cut hand, the result of a blow from her husband, he takes her to his father’s pharmacy to dress the wound (Fig. 2). Seeking to impress her, he shows her the poisons on the shelves, including strychnine, which he tells her produces the same symptoms as lockjaw. Pearl steals some of the strychnine and uses it to poison her husband, whose death is attributed to lockjaw. Pearl’s hopes of being with Dan are dashed, however, when her husband’s body is exhumed. Realizing that Mr Sutton will be called upon to examine the body, she tries to blackmail him by telling him about David and how she obtained the strychnine. Sutton defies Pearl and, rejected by Dan and certain of her fate, she throws herself into the sea. The Sutton children are reconciled with their father, who allows them to realize their ambitions.

British costume dramas of the 1940s and 1950s are most closely associated with two studios, Gainsborough and Ealing. But whereas Gainsborough period films created a lavish, baroque aesthetic and drew on ‘an extravagant and excessive visual language which went against the grain of British restrained realism’, Ealing histories were more concerned with moral respectability and with ensuring that bad characters received appropriate punishment.6 Both studios, however, albeit to varying degrees, drew on costume design, lighting, and narrative to construct an eroticized display of female sexuality. Film historian Sue Harper has argued that although there was some concern regarding the sensuality of these films, female audiences were particularly drawn to the historical genre, with its emphasis on clothing, hairstyles, jewellery, and make-up (see Fig. 2). As one young hairdresser explained in 1948:

I soon found out I enjoyed historical films, though I believe that the lovely costumes had a great deal to do with it, for I can often remember the times when I would come home and dream that I was the lovely heroine in a beautiful blue crinoline with a feather in my hair. I used to pray so hard for that crinoline.7

This simple observation makes plain the function of costume and the appeal of the female figures. While costume gives a sense of historical period and surface accuracy, it is far more important as a bearer of fantasy. The young woman is drawn to the costumes as a fabrication that triggers in her a dream of assuming the same look, of also dressing up. Clothes rationing had been introduced in June 1941 and ended in 1949, although the Utility clothing scheme, which regulated the amount of material and labour used in the production of clothing, continued until 1952. Little wonder, then, that in the years around 1948, the ‘lovely costumes’ and heroines in British costume dramas, the frills, bustles, lace, ringlets, bracelets, and chokers were the focus for female audiences.8

Pearl’s look is critical to the effect and affect of Pink String and Sealing Wax and it was used in all the promotional material. Before she has appeared on stage, she is described by one character in the play as ‘little better than a common prostitute’ and when she enters, the stage directions state: ‘She is a grammatically common, over-sexed young savage […] her obvious physical charms are marred by an incipient black eye.’9 The film tones this down a bit, with the script advising: ‘[Hers] is a hard loveliness, and the essential coarseness of her nature is always in danger of breaking through.’ Throughout, there is an oscillation between Pearl’s loveliness and her immorality that plays across the film and its marketing.

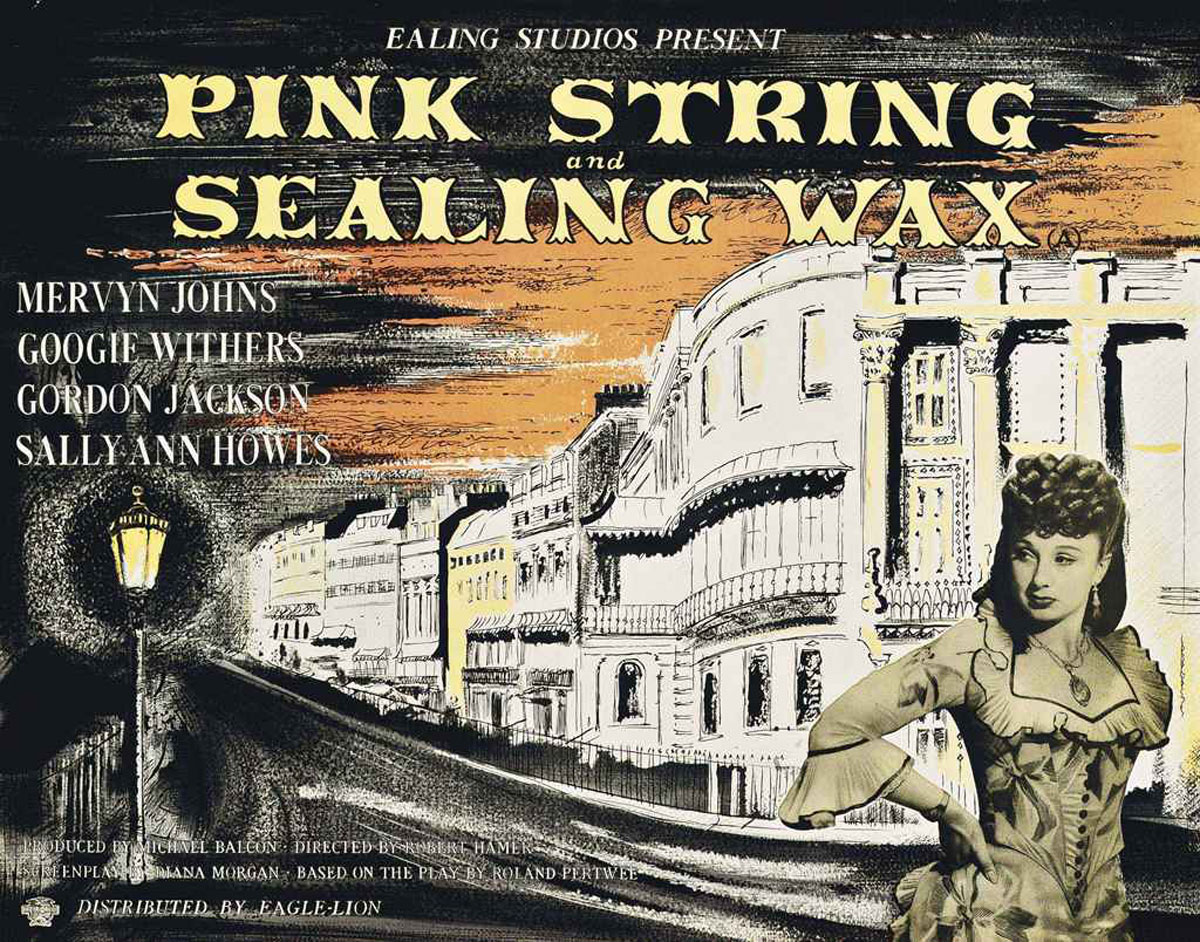

Ealing Studios was famous in the 1940s and 1950s for the artistic quality of its film posters. Whereas other studios were criticized for the tawdriness of their advertising materials, Ealing was praised for its employment of contemporary artists and designers, such as Edward Ardizzone, John Minton, and John Piper.10 Piper worked on one of the posters for Pink String and Sealing Wax (Fig. 3), a collage design in which a photographic still of Googie Withers as Pearl is placed in front of Piper’s aquatint of a Regency Brighton terrace. Piper’s print had first been published in 1939, in a collection of Brighton aquatints, introduced by Lord Alfred Douglas. Douglas writes as a Victorian, looking back fifty years and reminiscing about his childhood in Brighton: ‘I had forgotten all of this till I saw Mr Piper’s aquatints and discovered that the Brighton of my youth is still in existence, and that nearly all the old landmarks remain exactly as they were.’11 Douglas draws the twentieth century back to the 1880s and 1890s, to the Queensberry Rules and late Victorian morality. Everywhere, in wartime and post-war Britain, modernity stumbles over the images and remains of the nineteenth century. The atmosphere of the poster is enhanced with a darker sky and the addition of the large gaslight on the left. Googie Withers stands with her hands on her hips, looking to her right. It is an assertive pose and look, evoking the beauty and hardness of the film character, the sensuality of the performance that will drive the narrative.

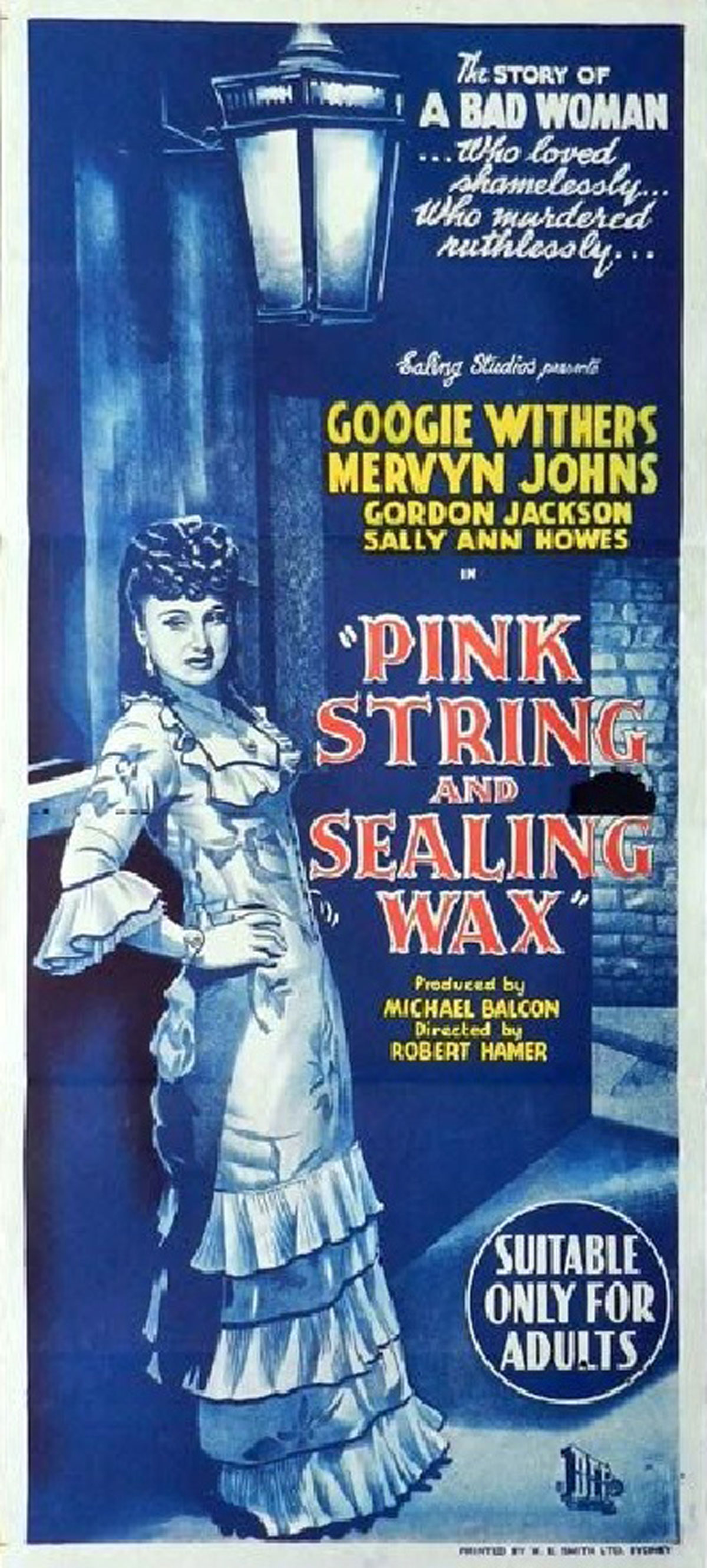

In a second poster Withers is fully transformed into a 1940s, Victorian femme fatale. In a broader and more sensational pictorial style, she is shown full length, as in the production still, outside the Dolphin pub, with plot taglines: ‘The story of a bad woman…Who loved shamelessly…Who murdered ruthlessly…SUITABLE ONLY FOR ADULTS’ (Fig. 4).12 In this poster Pink String and Sealing Wax becomes a Victorian film noir, with Pearl presented as a classic femme fatale. In her study of women in British films of the 1950s, Melanie Bell refers to ‘a specifically British variant of the femme fatale’, formulated around two key themes, ‘domesticity and sexuality’. Moreover, she identifies the poisoning wife as a particular variant of the dangerous woman.13 The character of Pearl adheres to this type, drawing on a long history of late nineteenth-century femmes fatales and its modifications within film culture. Pearl is a compelling combination of Gothic noir, dangerous sexuality, and historical merchandising.

Pearl refuses the role of obedient wife and, motivated by her desire for Dan, she exploits David in order to murder her husband. She threatens to destroy two homes, although both are already flawed: her own is already ruined by her husband’s drunken violence and her infidelity, and the Suttons’ is crushed by the repressive authority of the father. Like all femmes fatales, in the long history of the type, Pearl is manipulative, sexually active, beautiful, and dangerous, but she is in thrall to and weakened by her lover and her power is, therefore, equivocal and retribution inevitable.14 In a penultimate scene, perhaps the most powerful in the film, a long forward tracking shot follows the defeated Pearl from the pub, out into the street to the seafront, where she stands for a moment before throwing herself over the railing.15 While the suicide is a familiar, even hackneyed ending for the fallen woman, this lingering shot and Pearl’s glamorous attraction leaves the audience with a sense of loss at the death of the film’s most charismatic character.

Pearl’s filmic presence is a product of the bold and assured performance by Googie Withers, an actress who has been described as ‘perhaps the strongest, most commanding actress British films ever produced’.16 Withers was born in India in 1917, the daughter of an English naval captain and a Dutch-French mother. She left India at the age of seven and was educated in England and trained as a dancer, moving from roles in stage musical comedies to her first film role in 1935. During the war years she played more serious film roles and in 1945 made two films, including Pink String and Sealing Wax, for the Ealing director Robert Hamer, with a third, It Always Rains on Sunday, in 1947. Withers’s roles had substance, or at least, she gave them substance: women with histories and experience; women who were sexual and dangerous. She later stated that Pearl was her favourite role, in part because of the Victorian wardrobe she wore as the character.17

Withers and Victorian paraphernalia were the two greatest selling points of the film. The Ealing Studios pressbook reproduced publicity shots of Pearl (Fig. 5) and advised: ‘The Victorian period of the film is a primary angle on all exploitation matter’, suggesting link-ups with outfitters, jewellers, and stationers and also coming up with the idea that if there were any newspaper reports of murder or poisoning, they could be displayed in cinema foyers, ‘providing a link between local incident and the film’.18 At the same time that the studio concluded ‘NEVER TRUST A WOMAN’, it relished ‘the animal cunning of a woman: flashy, vamping, sex-appeal’. Reviews also focused on Withers, with the Sunday Graphic admiring her ‘bold, beautiful and wicked’ looks.19 Victorianism enabled a particular form of female sexuality, one masquerading in nineteenth-century costume, playing at being in the past, while exploring the gender issues of the present.

Pink String and Sealing Wax was released shortly after the end of the war and while its promoters encouraged links between the past of the film and the present, its Victorian interiors and costumes and its brazen leading lady made it a perfect escape from the task of post-war recovery. In the years immediately following 1945, Victorianism became increasingly visible in British visual culture, although always with a hard and dark edge to its beauty. The Festival of Britain in 1951 — a celebration of the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition — provided a focus for this attraction, with nineteenth-century elements peppered throughout the festival site and affiliated events. Artist, writer, and curator Barbara Jones celebrated the British vernacular arts in her exhibition ‘Black Eyes and Lemonade’ (London, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1951), displaying a gallimaufry of old and contemporary objects and their blend of ‘vigour and humour […] horror and realism’.20

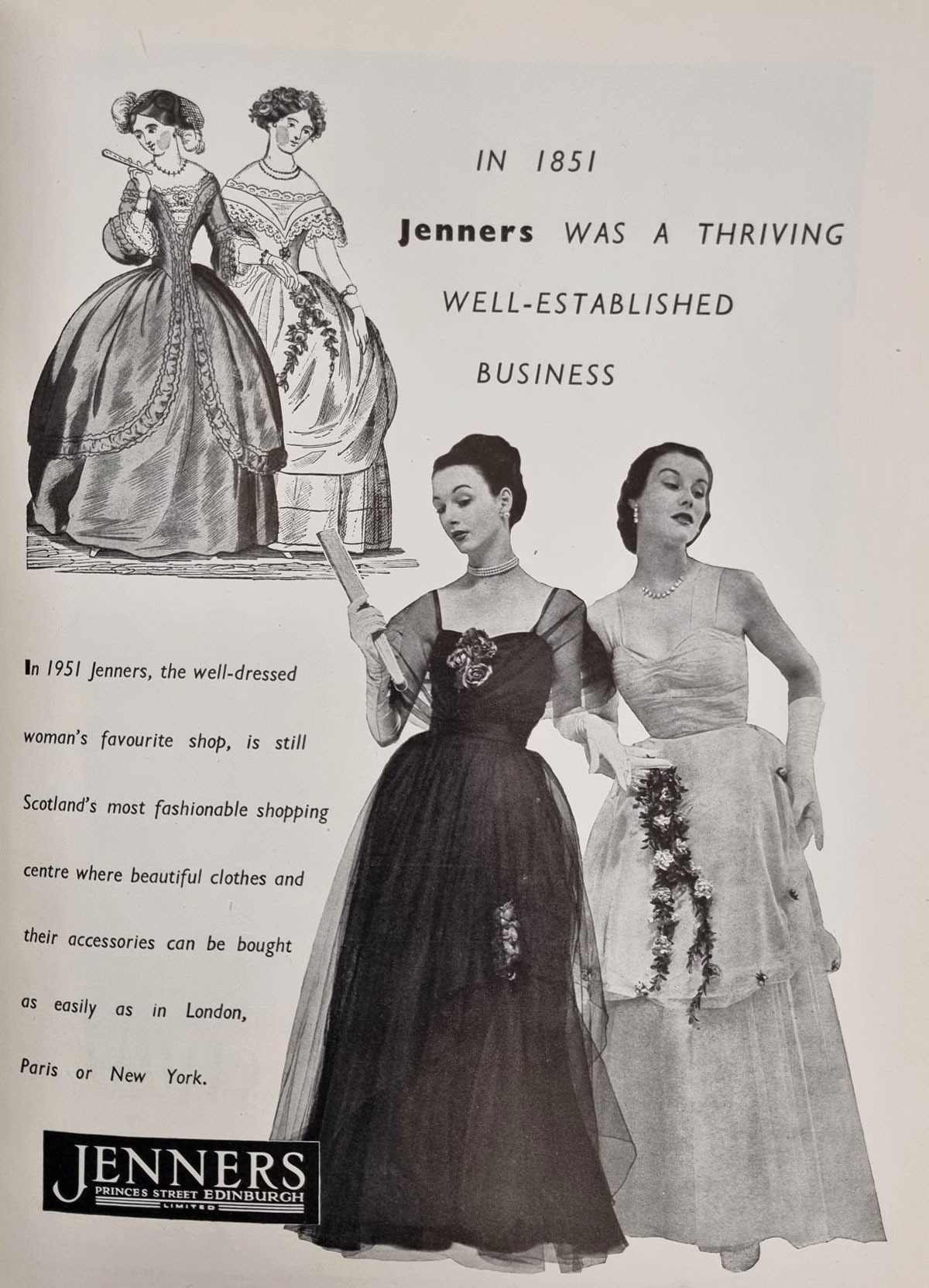

The festival events of 1951 deliberately recalled the times of 1851, with exhibitions of Victorian art, such as ‘East End 1851’, at the Whitechapel in the summer, followed by ‘Paintings by William Powell Frith’.21 In his introduction to the Frith exhibition catalogue, the curator James Laver noted: ‘now that the Victorian Period has outlived the indifference of the Edwardians and the contempt of the nineteen-twenties, we find ourselves looking at his pictures with a new interest.’22 Strong attendance numbers at the exhibition were put down by the gallery to ‘this time when Victorian achievements and values are being re-examined’.23 Businesses also picked up on this renewed interest in the Victorians, with companies such as Aquascutum bringing out its ‘Centenary collection’, and other fashion retailers drawing the connections between beauty in 1851 and 1951 (Figs. 6, 7).

The theme of sexual and moral hypocrisy runs like a current through all post-war Victorianism. Always a favoured trope within twentieth-century neo-Victorianism, this has never curbed the taste for the nineteenth century and appears, instead, to have sustained it. In his introduction to Victorian architecture, published in 1948, Hugh Casson described ‘this truly fabulous age’ as a facade, as ‘fragile and treacherous as stucco’, and in 1953 Vera Brittain claimed that ‘human society has gone forward since it stepped into daylight from the foetid atmosphere of Victorian hypocrisy’.24 Victorian Britain had a job to do in the post-war years; whether it was to be the fetid, corrupting world from which the nation stepped into the enlightenment of modernity, or the locus of sensual style and fantasy, it was always the launch for the now, the way in which the present defined itself. Pearl is a cipher for this multivalent fantasy of Victorian beauty, a figure who reinvents the Victorian past for the post-war nation and looks forward to the discourses around gender and sexuality of the second half of the twentieth century. We might now imagine a different ending, in which Pearl walks away from the seafront and continues to trouble with her ‘hard loveliness’.

Notes

- Beveridge referred to these as the ‘five giants on the road of reconstruction’. See Sir William Beveridge Foundation <https://beveridgefoundation.org/sir-william-beveridge/> [accessed 26 October 2022]. [^]

- Frank Mort, ‘Scandalous Events: Metropolitan Culture and Moral Change in Post-Second World War London’, Representations, 93 (2006), 106–37 (p. 123). See also, Mort, ‘Modernity and Gaslight: Victorian London in the 1950s and 1960s’, in The New Blackwell Companion to the City, ed. by Gary Bridge and Sophie Watson (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011), pp. 431–41; and Mica Nava and Alan O’Shea, ‘Introduction’, in Modern Times: Reflections on a Century of English Modernity, ed. by Mica Nava and Alan O’Shea (London: Routledge, 1996), pp. 1–6. [^]

- See, for example, Hilary Fraser, Beauty and Belief: Aesthetics and Religion in Victorian Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); Elizabeth Prettejohn, Art for Art’s Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting (London: Yale University Press, 2007); and recently, Jonah Siegel, ‘Beauty’, Victorian Literature and Culture, 48 (2020), 745–71. [^]

- London, BFI National Archive, Pressbooks Collection, Pink String and Sealing Wax, small pressbook, unpaginated, PBS 41317. [^]

- Roland Pertwee, Pink String and Sealing Wax: A Play in 3 Acts (London: English Theatre Guild, 1945). The title refers to the way that chemists secure parcels for their customers. [^]

- On Gainsborough costume dramas, see Pam Cook, Fashioning the Nation: Costume and Identity in British Cinema (London: British Film Institute, 1996), p. 17; on Ealing histories, see Sue Harper, Picturing the Past: The Rise and Fall of the British Costume Film (London: British Film Institute, 1994), p. 112. [^]

- Quoted in Harper, p. 140. On female audiences and costume dramas, see also, Cook, p. 77. [^]

- On the use of costume to ‘signal’ a specific period rather than as historically accurate, see Anne Hollander, ‘The “Gatsby Look” and Other Costume Movie Blunders’, New York, 27 May 1974, pp. 54–55, 58, 62. [^]

- Pertwee, pp. 26, 34. Script advice cited in Harper, p. 112. [^]

- For contemporary discussions of film posters and praise for Ealing designs, see Jack Beddington, ‘Can Film Posters Be Improved?’, Penrose Annual: A Review of the Graphic Arts, 43 (1949), 50–51; Osbert Lancaster, ‘Ealing Studio Posters’, Architectural Review, 105 (1949), p. 88. See also Nathalie Morris, ‘Selling Ealing’, in Ealing Revisited, ed. by Mark Duguid and others (London: Palgrave Macmillan on behalf of the British Film Institute, 2012), pp. 91–100. [^]

- John Piper, Brighton Aquatints: Twelve Original Aquatints of Modern Brighton with Short Descriptions by the Artist and an Introduction by Lord Alfred Douglas (London: Duckworth, 1939), unpaginated. The print used in the Ealing poster is of Kemptown. [^]

- X-certificates were introduced in 1951. [^]

- Melanie Bell, Femininity in the Frame: Women and 1950s British Popular Cinema (London: Tauris, 2010), p. 44; and on the poisoning wife, p. 45. [^]

- On the Victorian femme fatale, see Bram Dijkstra, Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986); and Rebecca Stott, The Fabrication of the Late-Victorian Femme Fatale: Kiss of Death (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1992). The literature on the femme fatale in film is extensive. See, for example, Shades of Noir: A Reader, ed. by Joan Copjec (London: Verso, 1993); and E. Ann Kaplan, Women in Film Noir, new edn (London: British Film Institute, 1998). [^]

- On this shot, see Brian McFarlane, ‘Ingénues, Lovers, Wives and Mothers: The 1940s Career Trajectories of Googie Withers and Phyllis Calvert’, in British Women’s Cinema, ed. by Melanie Bell and Melanie Williams (London: Routledge, 2010), pp. 62–76 (p. 65); and Melanie Williams, ‘A Feminine Touch?: Ealing’s Women’, in Ealing Revisited, ed. by Duguid and others, pp. 185–94 (p. 187). [^]

- Brian McFarlane, ‘Pink String and Sealing Wax’, in The Cinema of Britain and Ireland: 24 Frames, ed. by Brian McFarlane (London: Wallflower, 2005), pp. 53–64 (p. 56). See also, Brian McFarlane, Double-Act: The Remarkable Lives and Careers of Googie Withers and John McCallum (Monash: Monash University Publishing, 2015); and John McCallum, Life with Googie (London: Heinemann, 1979). [^]

- See McFarlane, Double-Act, p. 22. The costume design for Pink String and Sealing Wax is generally attributed to Bianca Mosca, although the credits only mention her in connection with the dresses of two other female characters. Marion Horn was the wardrobe supervisor. [^]

- Pink String and Sealing Wax, small pressbook, unpaginated. [^]

- Cited in Pink String and Sealing Wax, Press Cuttings, BFI Collections. See also, Evening Standard, 30 November 1945. [^]

- Barbara Jones, ‘Introduction’, in Black Eyes and Lemonade: A Festival of Britain Exhibition of Popular and Traditional Art (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1951), pp. 5, 7. [^]

- ‘East End 1851’, A Festival of Britain Exhibition by Arrangement with the Arts Council, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 2 May–30 June 1951; ‘A Festival of Britain Exhibition of Paintings by William Powell Frith R.A. 1819–1909’, Harrogate Corporation Art Gallery and Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 7 July–30 September 1951. [^]

- James Laver, ‘Foreword’, in Paintings by William Powell Frith (London: Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1951), unpaginated. [^]

- London, Whitechapel Gallery Archive, ‘Whitechapel Art Gallery Report 1951–52’, WAG/PUB/5/1/ Guardbook 4/49–9/51. [^]

- Hugh Casson, An Introduction to Victorian Architecture (London: Art and Technics, 1948), p. 5; Vera Brittain, Lady into Woman: A History of Women from Victoria to Elizabeth II (London: Dakers, 1953), p. 160. [^]