This article explores the relationship between networks and infrastructure by considering the material and immaterial meanings of the word network in relation to the connective role of physical and socio-technical infrastructural systems. In doing so we follow the injunctions of Ruth Ahnert and others to move ‘the discourse and analysis of networks’ forward ‘through collaboration and exchange’ at the intersection of different kinds of knowledge.1 In order to keep cultural history closely involved in those interdisciplinary conversations and so as to take account of the ‘long lineage of technological advancements and thematic assessments’ that should inform research in the digital humanities, we take our bearings from debates about the term network that belong to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries themselves and use a single 1802 manuscript tour of Wales and Ireland to test our approach.2

Ahnert and others further remind us that ‘scholars from the arts and humanities […] have been writing about networks for centuries, albeit from the metaphorical perspective, examining communities of practitioners, the dissemination of ideas, or the relationships between certain texts, images, or artefacts’ (p. 7). Among those earlier scholars is Samuel Johnson, whose explanation of the word network was often cited in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as the very essence of a bad dictionary definition:

Ne′twork. n.s.[net and work.] Any thing reticulated or decussated, at equal distances, with interstices between the intersections.3

The description does indeed confuse and Johnson’s reliance on the words ‘reticulate’ and ‘decussate’ hardly clarifies things. But the definition also achieves a kind of technical clarity in its account of a word whose meaning is constituted by material acts of division, marking, crossing, tying, and intersecting. Henry Hitchings goes so far as to praise Dr Johnson for a description that aims at the ontological identity of the word network itself, ‘a definition’ that he says ‘has technical integrity rather than working by analogy’.4 Part of that integrity involves an awareness of the reliance of networks on infrastructure. In Inhuman Networks Grant Bollmer suggests Johnson’s definition has the merit of showing how ‘network’ referred to physical objects as well as to a dematerialized, metaphysical connectivity. Earlier examples make the case: Bollmer points out that in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century usage, networks (or net-works) was the name given to ropes for covering hot-air balloons as well as rigging on ships.5 And as Ahnert and others put it, networks are etymologically connected to the material world of labour and connect, in many languages, to ‘the material act of weaving nets’ (p. 16). As networks expand, evolve, and change, they pass through developing infrastructural arrangements that in turn facilitate new technologies. These interconnections both express and shape history. Networks, however, also exceed or defy infrastructure at various points, not least when aspects of the material world fail to align or diverge according to formal lines.

Mapping networks

The complexity of networks has required painstaking and innovative research dating back to the dawn of digital methods in the humanities and remains a core area of critical activity. Growing fields such as computational literary studies and its application of tools such as natural language processing — and a proliferating suite of packages in popular languages such as R and Python — can count and visualize the recurrence of words of place names in letters, works of fiction, or other corpora of useful literary data. Such packages have fed many of the fields adjacent to and feeding into network analysis.6 Corpus analytics provides unparalleled insight into the connections within literary texts and their visualization in mapping packages such as Leaflet and data visualization suites such as Palladio. The growth of affordances in linked open data through schemata such as the Resources Description Framework (RDF) makes it easier than ever to encode links between people, places, concepts, and objects. A growing proliferation of tools for understanding texts at a variety of scales and levels of granularity proves that the ‘mainstreaming’ of network analysis is well underway.7 As a result, it is now possible to build low-cost large-scale analyses of texts that push in new directions by focusing on content itself rather than on the need to develop tools or infrastructure to support the content. In a time when funders and institutions fetishize novelty and innovation, there is a danger of losing sight of what can be achieved via the application of existing tools at different scales and for a variety of smaller purposes.

Enter the open source Recogito annotation environment, an initiative of the Pelagios Network.8 The free platform is designed to allow a scholar or network of scholars to collaboratively import texts and images, identify and mark named entities within them, and export the data in an open and interoperable format. Because Recogito makes tasks that were formerly time-consuming — geolocating place names, annotating text, creating corpora, working from a central environment — relatively simple, it offers the opportunity to focus on new questions that can be asked of texts when they are marked up in a consistent, open, and reusable format. Pioneering initiatives in literary Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial humanities such as Mapping the Lakes at Lancaster University showed the world of nineteenth-century textual studies what was possible, but it both developed and relied upon methods that require specialist and labour-intensive digital and spatial humanities methods to gain maximum benefit.9 Recogito speeds up these processes and allows us to explore deeper and more ambitious questions through cumulative gains in digital humanities. Put simply, the more time that is spent on developing and testing tools, the less can be spent on the quantity of annotation types and items in a corpus. By accepting the interconnection and intermingling of networks and infrastructures, we are left free to imagine further explorations that capture a broader contextual set of linked open data.

Learning why an ever expanding corpus of descriptors is important has never been more vital. Seeing networks as purely social or purely mathematical and instead embracing a more-than-human approach such as Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network-Theory and its legacies provides many more candidates for annotation and thus scrutiny in the close and distant reading of digitally mediated critical editions.10 But how do time-poor annotators using the standards of the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) respond to such complexity? The greatest challenge of annotation — from marking up a digitized primary source in TEI or creating linked open data — is to ascertain which corpora, which items within that corpora, and which descriptors within those items should be given attention. Why? Limited resources provide the main reason. Working on a single document may allow for a forensic account of its contents — a genetic edition, for example, that tracks word choices and changes over time — but material is infinite and resources are finite. There are also limitations to the number of texts available to convert into an annotation-ready format such as an XML (eXtensible Markup Language) document. In an environment of scarcity, albeit one taking great leaps in efficiency due to tools such as Transkribus and other forms of AI-powered OCR (Optical Character Recognition) and machine learning, it is necessary to make decisions about markup tags: who, where, what, when? And what else? Every class of words made visible to machine reading by the digital editor is an investment in both human time and computer resources.

As a result the possibility that an entire vocabulary of descriptors is being missed must be considered. In the future machine learning will allow a great deal more nuanced and ad hoc distant and close reading methods, but that time has not yet come. Even if we reach a world of vastly improved access, it will become even more important to know which questions to ask. Delimiting access to annotated text due to limited annotation is one pitfall, but perhaps a greater risk is a future where this work is leapfrogged by developments in machine learning while scholarly questions lag behind. We argue that it is possible to use the complex interactions between infrastructures and networks to shape digital methods of text annotation. A consideration of the interrelated workings of network as crossing and joining means asking what else might be relevant to reading a text alone or as a corpus, closely or at a distance. This question is fundamental because it affects decisions that shape projects, dictates what is computable and what is available for analysis, and sets priorities for future studies of the long nineteenth century.

The same notion can be more broadly expanded to envisage a densely woven net that captures fine-grained agencies on a broad spectrum from the human to the non-human, including the power and agency of weather. As Christopher Donaldson, Ian Gregory, and Patricia Murrieta-Flores put it in their discussion of tourism literature of England’s Lake District, tourist texts, letters, and travelogues reveal ‘a new alertness to the physical, affective, and imaginative experience of the journeys recorded therein’.11 The Mapping the Lakes project that generated their article offers a complex representation of the words ascribed to popular tourist destinations within the region. As a case study it reminds us how much more exists within the net and the interaction between networks and infrastructures. As a deep map, Mapping the Lakes offers a superabundance of meaning and connection beyond its bounds.

Digital humanities, as Mapping the Lakes demonstrates, provides powerful tools for the exploration of the interrelationships of networks and infrastructure. It can trace networks as experienced and recorded while also measuring their physical realities. But the contents of the chosen Mapping the Lakes texts and their affective register also demonstrate the potential of marking up and comparing unexpected elements of a text corpus using literary and historical GIS methods.12 The result was attentiveness to the links between points on a tourist itinerary of the Lake District and the emotions evoked, including difference in word use across time, class, and culture. The project demonstrated that the quantitative application of details that might otherwise be seen as ephemeral could have a variety of applications for digital humanities methods. It offers opportunities for complementary case studies that can expand our knowledge of a networked past while opening digital humanities research to the history of infrastructural developments.

Among the successor initiatives of Mapping the Lakes is the AHRC-funded Curious Travellers project, a digital edition of previously unpublished tours of Wales and Scotland with some parts of lreland, undertaken in the period 1760 to 1830 by a wide range of travellers. Principal investigators Mary-Ann Constantine and Nigel Leask worked with researcher Elizabeth Edwards to create an XML corpus of letters and tours that they consistently marked up with a series of four indices consisting of controlled vocabularies: persons, places, books, and artworks.13 The function of this study was to reflect a ‘broader ferment of different ways of thinking about places and their human and natural histories’ at a time of critical change when familiar narratives of touristic travel were not solidified.14 The project provides detailed information across these four categories within a large corpus. However, the range of categories is necessarily limited by the scope of the work undertaken: it is better to know a great deal about the four most relevant categories of named entities within the corpus and focus on preparing previously unavailable texts for publication. The project has prepared for the future by allowing easy download of XML documents from the collection in anticipation of further interoperable use for the markup created by the project.

Questioning networks

Interoperability does not belong to the twenty-first century alone and nor does it remain distinct from interconnectivity. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century public works at sites such as docklands, ports, and post offices required connections between stage coaches, rail, and steam-powered vessels, expressed in culture in terms of what Ruth Livesey calls ‘a natural formal affinity’ between journeys, networks, and narratives.15 That affinity is explored in depth within Maria Edgeworth’s Harry and Lucy stories (1801–25), where two adolescent children seek out knowledge about the world in which they live, spurred on and often challenged by their parents. The context for Edgeworth’s educational writing is the brisk succession of technological innovations seen in the period between about 1780 and 1835, a revolution keenly observed and discussed by Edgeworth and her family in the Irish Midlands. The characters of Harry and Lucy are first found in Early Lessons (1801), emerged again in a continuation of Early Lessons in 1814, and made their final appearance in Harry and Lucy Concluded (1825). Their parents practise a mode of ‘gradual instruction’ while their father is ‘the most technical of all Edgeworth’s pedagogues’, regularly talking to the children about steam, manufacturing, and electricity.16 To narrate the sequence of Harry and Lucy stories in terms of the transport revolution that so often occupies the attention of the child characters, the books begin just before Thomas Telford’s extensive modernization of the road network from 1808, continue into the era of the arrival of steam-powered sea travel in the early 1820s, and conclude before the advent of the railways in the 1830s. The educational model is observational, participative, and collaborative, allowing for tensions, disagreements, and discussion. As the children grow older and the stories progress, their respective genders start to make a difference. Still, they share qualities of curiosity and an endless appetite for knowledge, whether in the form of experiments, conversations, drawings, or books. They probe topics of shared interest together and, through doing so, discover difficulties arising from the question of what interconnectedness might mean, including a playful meta-discussion of the meanings of connectivity in its material and immaterial dimensions.

At the start of the third volume of Harry and Lucy Concluded, the adolescents find themselves by the sea near Plymouth in England ‘with but few books’ to occupy their time. They are astonished and absorbed by ‘the sea! the sea!’ and Harry starts to wonder about the prospects of crossing the sea by steam-powered vessel. The children occupy themselves with coastal pursuits — Harry wants to build a bridge, cut a canal, and create a lock by the seashore while Lucy collects and identifies seashells.17 Harry’s infrastructural experiments are presented in detail. He wishes to ford a stream with a ‘real, substantial arched bridge’, an object that will be of ‘public and private benefit’ (III, 79, emphasis in original). With help from a mason’s apprentice, he measures lengths, lifts stones, and calculates curves. Meanwhile, rain comes and the children retreat indoors. There, they find a copy of Samuel Johnson’s dictionary — ‘the little octavo Johnson, in which there are only the meanings and the derivations of the words’ — and fall upon it for entertainment (III, 95).

For Harry and Lucy this begins an extensive lexicographical discussion that focuses on the meaning of the word network, the difficult definition offered by Johnson with which we began. When Harry and Lucy turn to Johnson’s dictionary, the first word they consult is darn, ‘a woman’s word’ according to Harry who asks his sister if she ‘can explain the meaning as well as it is explained here by a man’. Lucy, ‘her colour rising at each ineffectual trial’ fails to produce anything close to Johnson’s crisp clear definition of the verb to darn: ‘To mend holes by imitating the texture of the stuff.’ Next comes network. The ensuing discussion, which turns on the meanings of that term, allows Lucy the upper hand, a ‘revenge’ afforded by Johnson’s abstruse definition (III, 95).

Puzzling over Johnson, the confused children turn to the definition of the Latinate word decussate, which, they learn, means ‘to intersect at acute angles’; an action that Harry compares to the making of a net, where ‘each mesh or stitch is intersected, is it not? at acute angles’. Lucy disagrees with this account, contending that ‘to intersect, means to cut in two, does not it? and the mesh of the net, instead of being cut in two, is joined at the corners.’ She draws on the transitive meaning of intersection as crossing, as in the OED definition of intersect: ‘To divide (something) in two by passing through or lying across it; to cross.’ Harry, however, turns to geometry to support his understanding of intersection as joining, also found in the OED definition: ‘To pass through or across (a line or surface), so as to lie on both sides of it with one point (or line) in common.’ Johnson’s dictionary confirms that they are both right, ‘for there are two verbs to intersect’. Harry continues by explaining that ‘one is a verb active, meaning “to cut, to divide each other”’, while ‘the second is a verb neuter, and means what I told you’, and so is defined as ‘to meet and cross each other; as in your net the threads do meet and cross at the angles’ (III, 95–97, emphasis in original).

As the children work through a sequence of words connected to network they return the reader to a meaning that is something very like darning: cutting up and joining ‘stuff’ together, a kind of mending that is close to ‘women’s work’. The primary OED definition of network summarizes Harry and Lucy’s findings very well: ‘Work (esp. manufactured work) in which threads, wires, etc., are crossed or interlaced in the fashion of a net; frequently applied to light fabric made of threads intersecting in this way.’

The examples given in the book often arrive at such moments of clarity via mistakes and misdirection. When the rain stops, Harry discovers that his bridge has entirely disappeared, swept away by the rain-swollen stream: ‘oh! disappointment extreme! oh! melancholy sight’ (III, 102). Networks, it seems, belong indoors within the realm of ideas and discussion where they are isolated from the kinds of variables that might create frictions or disruption. Infrastructural projects, on the other hand, are tangible, if threatened, outdoor structures. In this case Harry’s errors mean that he makes a better bridge in the end, one that can withstand the effects of weather. First though, the bridge-building project has to pass through an abstract discussion of the meaning of the term network, as if the latter concept were a player in the unfolding infrastructural drama.

Harry and Lucy’s efforts to define network, framed as they are by an infrastructural project requiring tools, men, and expertise, illustrate the porous relationship between infrastructures and networks. Edgeworth asks readers to stop and consider the mutually constitutive relationship between these concepts, one aimed at practical improvements and with a material dimension and the other related to the immaterial realm of ideas. In the example we have drawn from Edgeworth, infrastructure itself belongs to a network of socio-technological arrangements between technologies and their users. Harry’s bridge-building project is motivated by his desire to spare his mother’s feet from getting wet and indirectly leads him to become entangled in an argument with his sister about etymology; such affective ties themselves testify to a social network.

The example belongs to the realm of fiction, in the case of Edgeworth a kind of imaginative writing aimed at children that stays close to the material realities and emerging technical innovations of a changing world. Harry’s bridge and Lucy’s seashell collection take their place among a wider network of examples and experiments that make up a set of stories intended to ‘exercise the powers of attention, observation, reasoning, and invention’ (I, p. ix). The approach combines literature and science and works via a ‘consonance’ between Edgeworth’s ‘compositional method and the book’s pedagogical objective: the characters’ cognitive development […] conforms to […] the book’s episodes, which examine and analyze a series of scientific and technological inventions’.18

As the infrastructures of the Industrial Revolution developed, so too did the narrative forms needed to express the connections that they made possible. But the many literary visions of steam — ‘this abridger of time and space’ — imagined by writers including Edgeworth, Walter Scott, and Percy Bysshe Shelley run counter to a history of technology approach where progress can be seen to be slow and incremental, the product of ‘long term and slowly rising trends’.19 Steam first arrived on the scene when James Watt (a friend of the Edgeworth family) patented the steam engine in 1784. Despite what Jon Mee describes as ‘a tendency to treat Watt’s engine as having had an immediate effect’, it was slow to make its presence felt. For the cotton industry, for example, steam did not become the dominant power source until the 1830s and steam-powered printing presses only become common in the same decade. As Mee argues, the ‘uneven process of industrialization’ has consequences for contemporary scholarly practices including debates about literary and cultural periodization (p. 229). That early uneven history of the machine age can also inform our understanding of machine-assisted processes of cultural history in the digital humanities. In that spirit of incremental rather than disruptive developments, we continue here with a discussion of the analysis and visualization of Mary Anne Eade’s ‘Journal of a Tour from Clapton through North Wales to Ireland’ (1802) in which we explore the co-dependence of network and infrastructure in the context of small-scale and low-cost research and practice.

Touring networks

In one understanding, literature itself exists as a dematerialized form of connectivity; a system of interconnected immaterial ideas and concepts that also relies on a publishing infrastructure built for the movement and circulation of books. The challenge posed by the example that Edgeworth develops within the Harry and Lucy books is amplified in the case of travel literature, a type of non-fictional writing that similarly exists at the intersection of material and immaterial meanings. Travel literature might be thought of as a network of texts, private and public, that draws meaning from a collection of features including topography, transport, climate, culture, and communication. Within nineteenth-century travelogues and letters, enthusiastic observers (including Edgeworth and her family as well as Mary Anne Eade) routinely describe new roads, railways, bridges, and piers even as they avail of social networks that join up experiences across time and space.

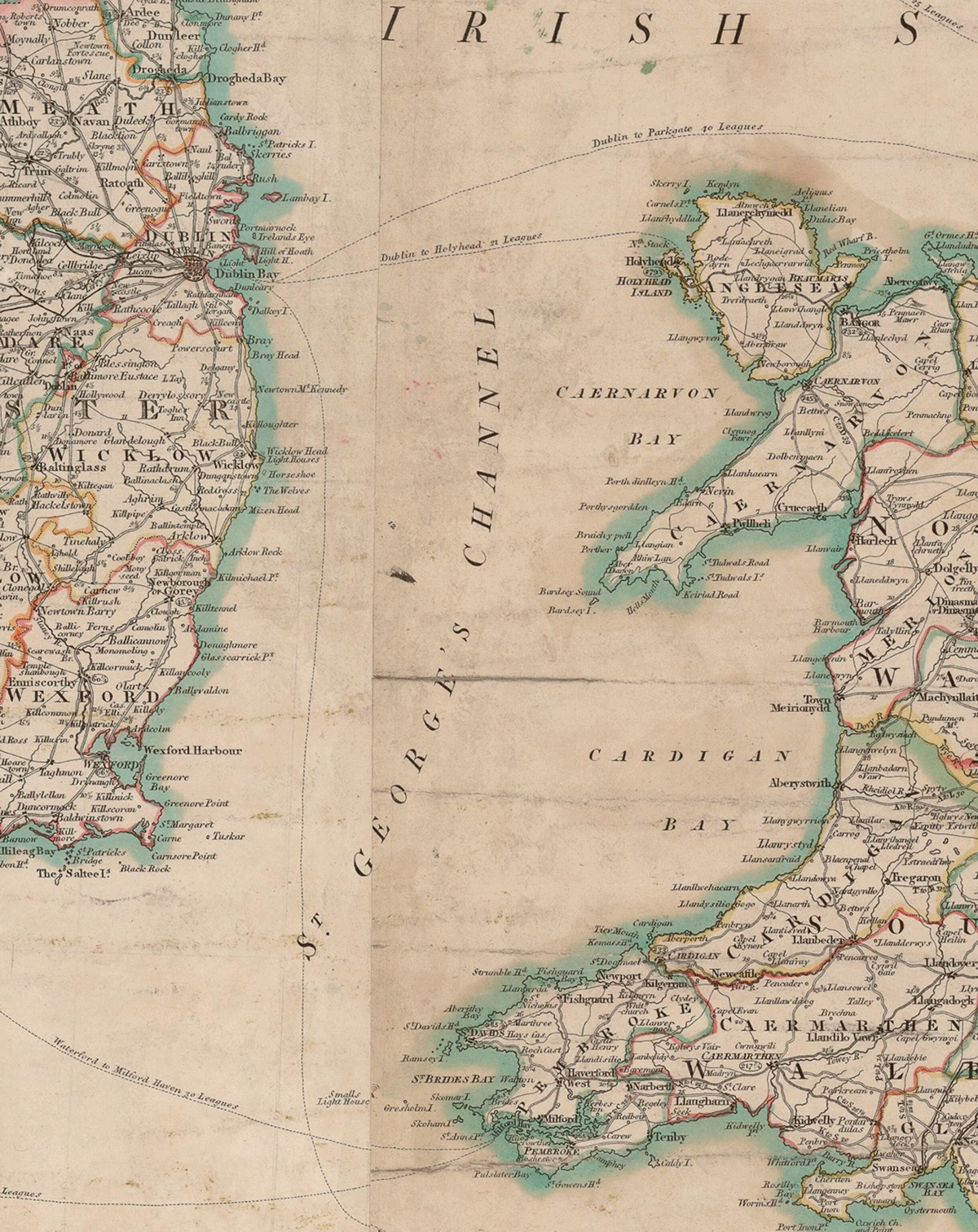

It is at this point that our case study begins, with a Curious Travellers text that includes an XML document containing the digitized National Library of Wales edition of Eade’s ‘Journal of a Tour from Clapton through North Wales to Ireland’.20 Eade’s journal records a journey that she took in the spring of 1802 in the company of her husband William Eade. They left Clapton in North London on 14 May 1802 and travelled through the English Midlands, into North Wales, Dublin, and County Wicklow before returning to London on 19 June (Fig. 1). She was one of many travellers who undertook a journey to the peripheral parts of the newly United Kingdom in the early years of the nineteenth century, partly motivated by the difficulty of journeying to Continental Europe during the long war with France. In August of the same year, Dorothy Wordsworth journeyed to the Highlands with her brother William and their friend Coleridge and she also kept a journal, not published until 1874. Mary Anne Eade’s tour, which remained unpublished until the Curious Travellers project, was written for the amusement of a younger sister left at home, who had herself produced an earlier tour of South Wales. The elder sister imagines the text as ‘a long imaginary conversation’ with her sibling. A short preface by her husband, dated March 1803, reveals that Eade (b. 1778) died less than a year after the completion of her tour. In Elizabeth Edwards’s description, the tour is ‘not just an extended postcard, then, but also a form of gift exchange’: testament to an affective network that found expression on the infrastructure that joined Ireland to Britain by road and sea.21

Fairburn’s Map of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (detail), 1802, BnF Gallica <https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53102715g>.

The tour can be considered as part of what Seán Hewitt and Anna Pilz describe as an ‘archipelagic archive’, encompassing the letters, ideas, technologies, and infrastructures of an interconnected empire, including biodiverse ecologies and journeys across water.22 Although Eade describes herself as not ‘a thorough traveller yet’, she is a keen observer with a brisk and lively writing style (f. 57v). Her unpublished private journal illustrates the paradox of letter writing as described by Isobel Armstrong: personal communications in which a literary understanding of space and place are ‘grounded in a common externality’. Armstrong describes this in terms of ‘the impossibility of thinking space away, and the infinitude of a plurality of spaces’.23 Space is realized in language and represents lived experience but is also ordered by a spatio-temporal reality that can be measured. This concrete existence for a travel network traversed by the letter writer sits alongside the role of network as an abstraction of space. Although network and infrastructure begin to diverge at this point, it is also impossible to hold networked space, understood according to formal principles, apart from experiences endured on the road or at sea.

Much of Eade’s attention is focused on the emerging industrial landscapes of the Midlands and North-West, so that space unfolds as infrastructure. She experiences time as ‘galloping’ along and is happy to dispense with particular places in favour of progress on the road: ‘Nothing of consequence occurred between Aylesbury and Buckingham’ (f. 7r). Even the famed beauties of Stowe gardens are registered in the mode of nothingness: ‘to nature they were indebted for nothing but space’ (f. 7v). In Warwick she finds the ‘the country for the most part flat & insipid’ (f. 11v). Arriving in North Wales, though, the couple are entranced by the ‘immense aqueduct which is building over the Vale of Llangollen from the Ellesmere canal, when compleat [sic] it will be a very noble work, at present it is in a very unfinished state’ (f. 21r). And in Birmingham she and her husband availed of their associational network to make connections and facilitate access to parts of a city that they experienced as one of the great spectacles of the Industrial Revolution:

William was acquainted with a young merchant here, of the name of Hunt; who came to us the moment he heard of our arrival, & with the greatest kindness & attention gave up the whole day to shewing [sic] us the curiosities of the town. (f. 14r)

The reference is to Harry Hunt, a Birmingham businessman with whose mother and aunt the Eades took tea. In Birmingham the pair are curious to see the latest technologies and eager to describe them. In Edgeworth’s text Lucy describes Birmingham as ‘the great toy-shop of Europe’ and longs to visit the ‘grand works’ of Matthew Boulton (1728–1809), the Birmingham-based engineer, manufacturer, and entrepreneur who worked on a steam engine patent.

For Mary Anne Eade Birmingham is at once ‘a vile dirty place’ and a compelling spectacle. When she and her husband visit an ironworks, her language moves into a fluent rendition of the register of the sublime:

The sight of them was truly astonishing, but I must own they filled me with as much terror as wonder: the deafening noise occasioned by the stupendous wheels, which worked the still more formidable hammers, the bars of red-hot iron which the men were continuously running to and fro with in all directions, & the innumerable sparks that flew all round, made the scene perfectly horrific. (f. 16v)

As well as watching steel being cast, the Eades visited the iron bridge built by Abraham Darby and completed in 1779 to cross the River Severn, the first bridge to be made out of cast iron. En route to Shrewsbury, William Eade descended a coal pit and saw the newer iron bridge at Coalbrookdale. In the cauldron of the Industrial Revolution, the Eades saw the land being remade as coal is pulled from the earth, conveyed along the canal arteries of England, fuelling a furious growth of activity. The crucible of this change is exemplified by the mine, the bridge, the traveller, and the ideas passing between them along the associational networks that shaped the Industrial Revolution.

Building networks

At this point, the connection between interconnection, infrastructure, and networks on one hand and annotations and linked open data on the other begins to emerge. Capturing a snapshot in time taken amid rapid interrelated social and technological change requires an understanding that a wide variety of words, encompassing a range of definitions. In a perfect world we would have all the information available at our fingertips. But without machine learning, material that is not annotated is not machine readable and thus not computable without the kind of extensive corpus analytics that are beyond the scope of many scholars. Cumulative, collaborative, linked and open data connecting clean and digitized texts such as the Curious Travellers Eade edition provide us with the opportunity to build on the work of predecessors and continue to deepen the links between texts. In the case of Eade’s tour, we use weather — that elemental and enduring challenge to infrastructural rationality — as an example. As Karin Koehler puts it, ‘infrastructures — promised or realized — often support narratives through which dominant political formations perpetuate and renew themselves, but they can also facilitate alternative visions.’24

Investigating the network and infrastructure of Eade’s journal was conducted by annotating the XML data using Recogito. This allowed people, places, weather, and time to be marked up and a visualization of the journey to be created.25 To begin this process, it was important to consider the following: What data are available? Where can they be acquired? How many sources are available? In short, by reducing the time taken to annotate the texts, the task becomes more oriented on the logistics of corpus making. Being able to take advantage of the efficiencies inherent in Recogito — low barrier to take-up, collaborative tools, connection to existing resources such as georeferenced gazetteers — allows new questions to be developed. By reducing the time required to annotate texts, it is possible to allocate time and labour to the digitization and preparation of the corpus without sacrificing the depth of annotation. When time is limited, economies must be made. As automation and open resources open up new opportunities, time can be strategically used to achieve more than would otherwise be affordable.

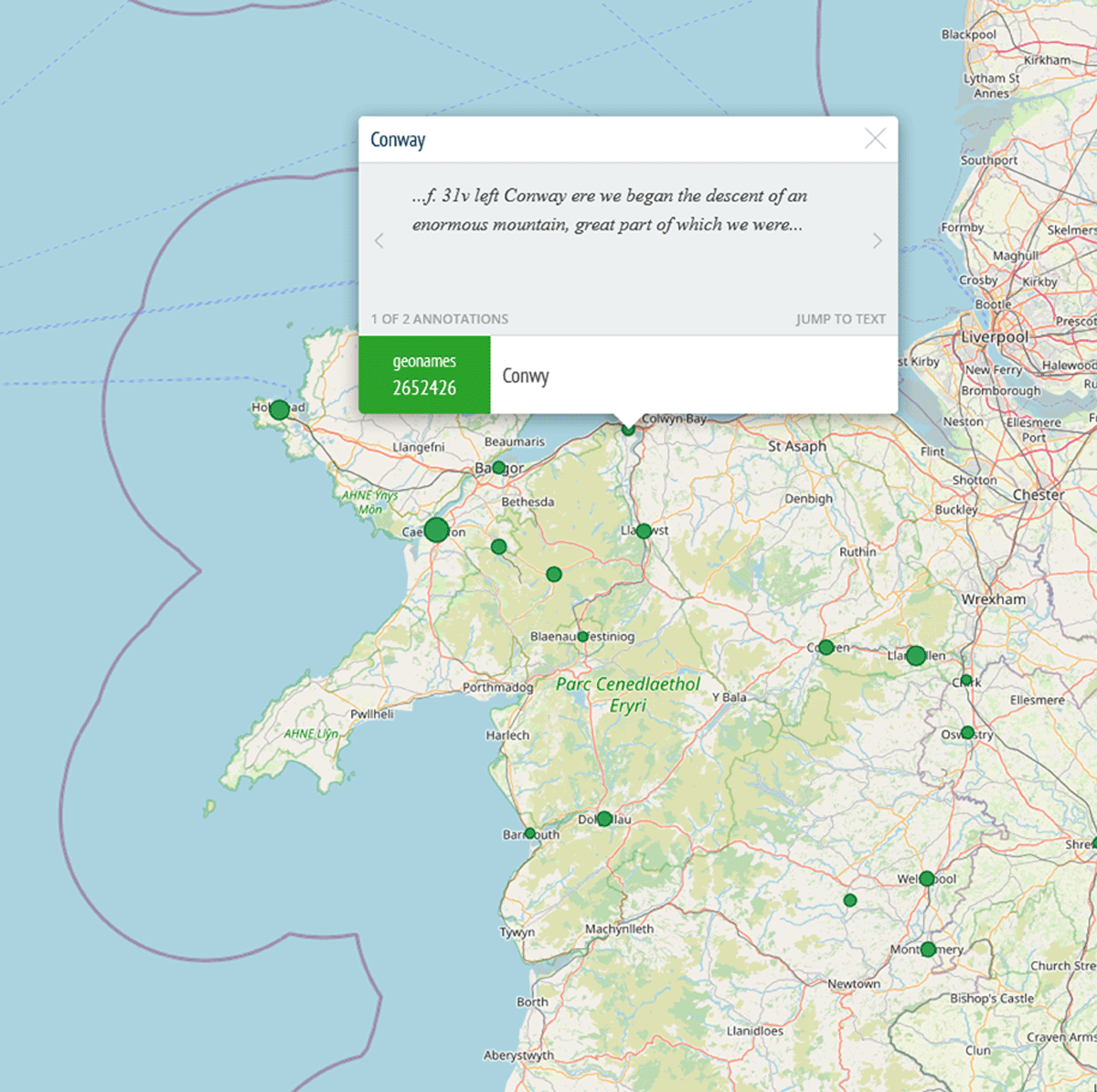

To begin the process of finding the network in Eade’s journal, people and places were identified and tagged (Fig. 2). These initial simple parameters gave a base of information and initial structure which could then be explored further. Following definition of these initial parameters of names and places, additional data points could then be investigated, including weather descriptions and timestamps. These offered a richer annotation structure that could be marked up within Recogito and allowed further exploration of the infrastructural details.

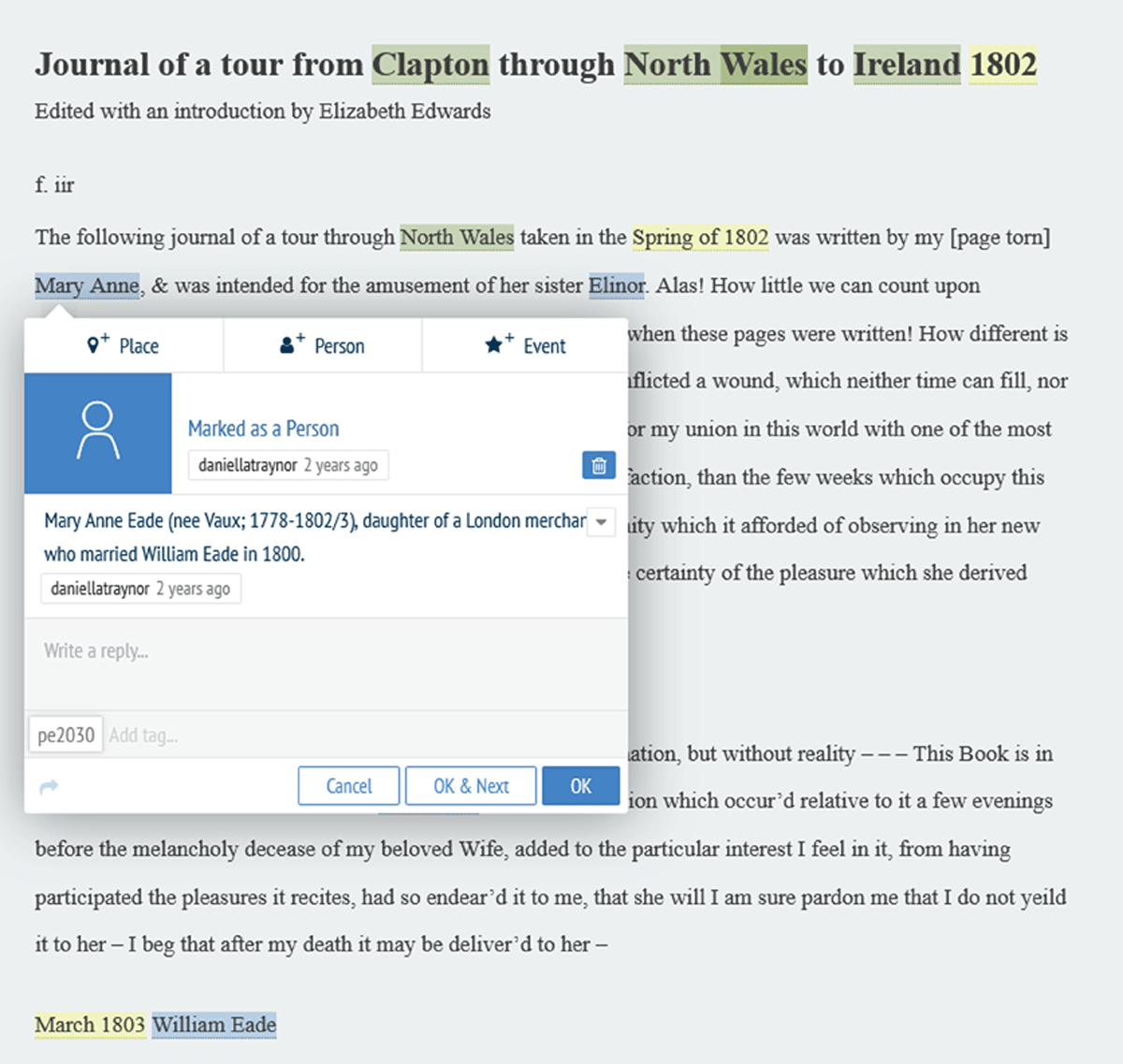

Recogito has a built-in annotation assistance process that allows for the recognition of marked-up strings and the option to apply that rule throughout the text. As each of the above parameters were defined, manual confirmation was used to minimize errors. The initial stage of the process was to identify all the various place names within the journal, tagging them accordingly and confirming the location. Recogito uses a variety of gazetteers for searching historic places and HistoGIS, Pleiades, and GeoNames were used to map the journey. Annotating the places and geotagging the locations created a rich visualization. Another essential part of the annotation process was the accurate marking up of people’s names. These were annotated, and a comment was made about the person from the Curious Travellers database of persons, which lists TEI persName attributes for each individual and a TEI note field containing biographical information (Fig. 3). The person was also tagged using their XML ID from the dataset. This began the process of building out the network and showing the interconnectedness of the people mentioned in Eade’s journal.

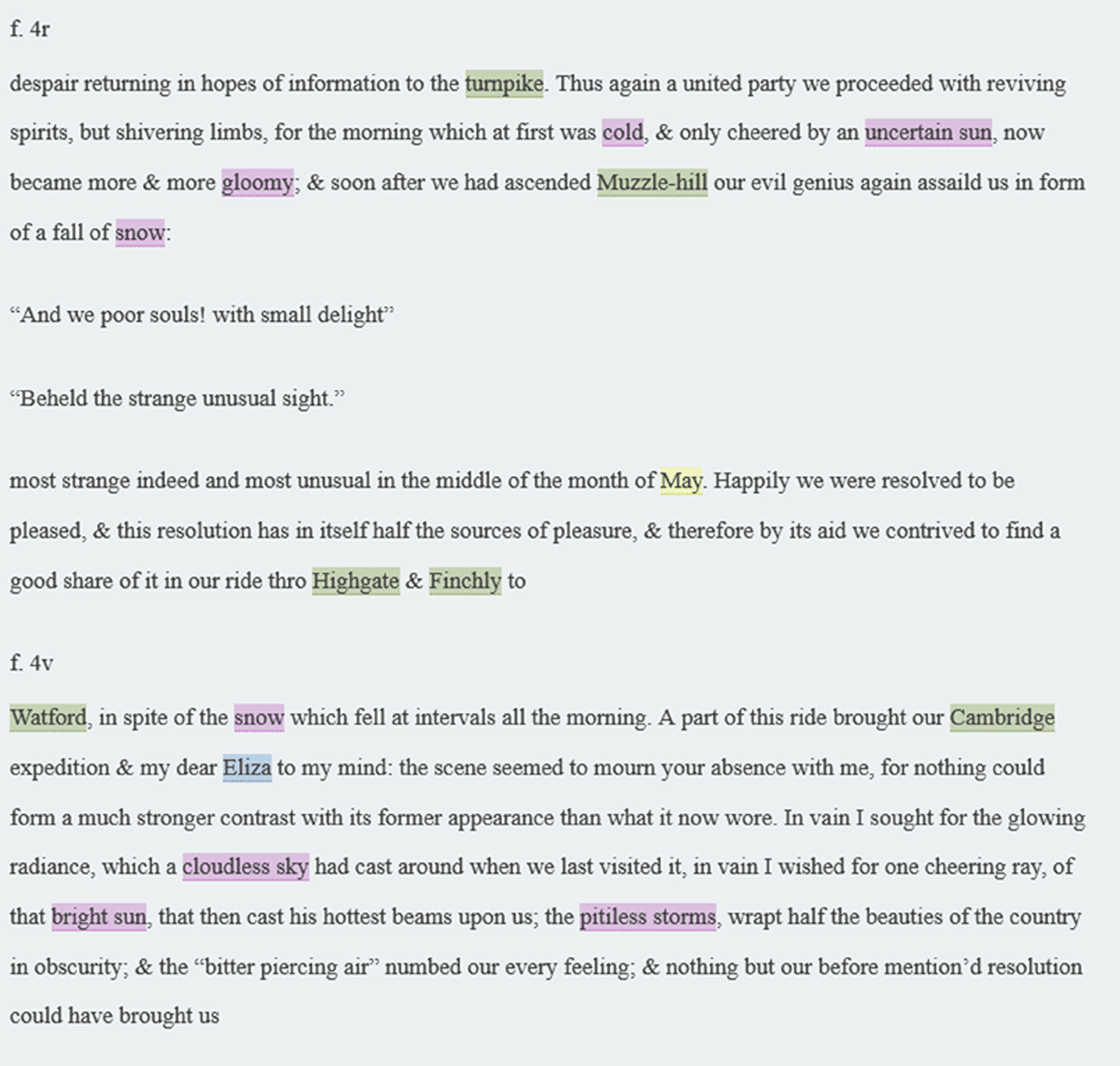

A sample of the annotation of these characters can be seen in Figure 3. Once this initial process was completed, further annotations identified weather and time frames mentioned in the journal. Weather was marked as an event and tagged with either adjWeather being an adjective for the weather, dynamicWeather for a current condition happening at that time, or staticWeather for general terms for the weather condition along the journey (Fig. 4). Figure 4 shows an example of the different types of weather described. Here ‘cold’ is an adjective describing the weather and tagged adjWeather, ‘uncertain sun’ as staticWeather, and finally, ‘snow’ which is tagged dynamicWeather. This gave the ability to distinguish between the various types of weather, adding depth to the markup and helping us work towards a fuller realization of the conditions experienced by Eade, including instances of proximity between weather descriptions and infrastructure. Weather conditions shaped the journey in material ways, as when the Eades arrive at the Menai Straits. Because the wind is favourable, they put off their planned visit to the Parys copper mines and press on for Anglesey, where information garnered en route allowed them to make a timely Irish Sea crossing. Research at scale is needed to establish the value of tracking highly specific weather vocabulary in a tour such as this one but the approach might in future be mapped onto the growth of quantitative weather methods across the nineteenth century.26

Limitations

The annotation of Eade’s journal offers insight into the connections and network found within the text. But the tour opens on absence and loss, as the couple say goodbye to their beloved son. They go on to lose their servant on the road, at which point the narrative expresses an uneasy blend of anxiety and comedy. Such affective registers are a challenge to annotation while relationships or people that are described in casual language or suggestive speech (rather than directly named) are also a challenge to digital methods. The role of their servant, Benjamin, remains obscure. Eade’s child was often referred to as her ‘darling boy’ or other variations of the same. A working knowledge of interpersonal relationships is needed and this process could not be automated. Infrastructure can also afford intimacies, as when Eade greets a rugged and exposed headland along which all travellers to Holyhead had to pass as ‘my old friend Penmaen Mawr’ (f. 50v). The crossing so fondly addressed by Eade was soon to be superseded by a new line of tarmacadamed road engineered by Telford, running along the base of the mountain.

A further limitation that we experienced in using Recogito for network annotation was that misspelled place names or ambiguous descriptions of places were difficult to tag geographically. Places that were mentioned but not passed through had also to be included in line with best annotation practice and following the criteria for the initial parameters. There is currently no way to adapt the visualization to differentiate between these two types of place names and adding this feature could be beneficial for future annotation processes of the same type. Equally, place names such as ‘Ireland’ or ‘Wales’ made the visualization of the data complex. In the tour Wales is often realized via the experience of specific sites and sounds. The Eades hear the harp being played at Oswestry as they prepare to leave England and go on to imagine the country that lies before them in highly generalized terms: ‘Wales that land of wonders I had so long wished without hope to contemplate, was actually within a few miles of us’ (f. 19v). Such descriptions are challenging, but further work with other annotated texts will enable improved visualizations.

Another Lancaster-based project, Chronotopic Cartographies, suggests that the spaces of literary texts can be analysed, visualized, and mapped with care and attention to their existence in real-world spaces and symbolic and figurative spaces, oscillating between references to real-world places and dreams, fantasies, or unreal episodes.27 Project categories include spaces of exile (places which no longer exist or cannot be returned to), nested worlds (integrated real and fictional worlds), and indefinite spaces (topographic elements deemed real but not place-specific). Only by seeing imagination and observation or uncertain and concrete categories as part of a chronotope — a unique configuration of time and space within a given narrative — can we apprehend travelogues more fully.28 A further challenge is found in the travellers’ reliance on informal networks of knowledge that are nearly impossible to capture or recreate. When the Eades cross Anglesey en route to the port at Holyhead, they learn from fellow passengers that ‘no pacquet leaves the Head on Tuesdays a circumstance of which we were before ignorant’. They make haste and reach Holyhead ‘a distance of three & twenty miles in three hours & a half’ (f. 34v). Here, ‘the Head’ serves as a helpful example of a place name disguised as a body part in a way that raises problems for machine-assisted reading.

Despite these difficulties, the ability to add a rich data visualization to Eade’s journal creates its own network of understanding. As we annotate and mark up nineteenth-century letters and accounts of travel and must choose which items are worthy of being included in the necessarily limited categories that enable machine-assisted reading and network analysis, we must recognize that proper nouns are not enough. Infrastructure is always social, responding to and shaping social attitudes in a rapidly changing world. As Tim Edensor, Kaya Barry, and Maria Borovnik put it, ‘in carrying out everyday tasks and ordinary practices, people habitually sense place and move through it, for the most part, without thinking, while possessing a competence borne of repeated practice’; and we share ‘weather-worlds’ in which ‘we perform everyday habits that respond to regular patterns of rain, cold and heat, often unreflexively managing daily routines that accommodate the conditions through which we move, work and play’.29 The categories of who, where, and when do not tell the whole story of a network or an infrastructure. To understand the complexities of a network, metadata of travel such as weather set the conditions for life-worlds that foster and respond to emotion, imagination, social ties, and other logistics of travel. Small human decisions such as when to stop for the night and when to rest, or human frailties such as seasickness or illness flow along lines laid down by infrastructure. These are qualities that are well captured in travel texts such as Eade’s — as when she observes that a rainy ride to Oswestry would not be possible without the protection of the ‘oil silk’ that she wears — but can be difficult to realize within current digital descriptors. The role of observation and curiosity can also take in environmental forms of noticing as when some recent rain (tagged as weather) releases ‘fragrant perfumes’ (f. 47v).

But Eade’s encounters on the road also yield forms of incomprehension and inattention to linguistic difference: Eade’s North Wales is peopled by ‘urchins’ who only use English when they ask for money. Researchers too ask for money as we develop new questions and build archives and corpora. This article has sought to show how new interventions can be made using existing tools but investment is needed in order to build a corpus of texts. Following on from Andrew Prescott’s suggestion that researchers benefit by connecting the history of the Industrial Revolution to contemporary challenges in digital humanities, we have proposed an understanding of DH itself ‘as a process of incremental development’ within small-scale and low-cost research and practice across scholarly networks.30 Like Harry and Lucy, we have approached the task by working with the tools at hand and shown how scholars, infrastructure, and research aids can mutually shape one another, albeit in uneven ways. Cultural texts and our curiosity about them can drive computer-guided humanistic methods as we ask questions and poke holes in the net.

Notes

- Ruth Ahnert and others, ‘Introduction: The Network Turn’, in The Network Turn: Changing Perspectives in the Humanities, ed. by Ruth Ahnert and others (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), pp. 1–9 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781108866804> (p. 6). [^]

- Margaret Kelleher and James O’Sullivan, ‘Introduction’, in Technology in Irish Literature and Culture, ed. by Margaret Kelleher and James O’Sullivan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), pp. 1–7 (p. 7). [^]

- ‘Ne′twork. n.s.’, in Johnson’s Dictionary Online, ed. by Beth Rapp Young and others, 2021 <https://perma.cc/VS6K-A2BN> [accessed 14 September 2023]. [^]

- Henry Hitchings, Dr Johnson’s Dictionary: The Extraordinary Story of the Book that Defined the World (London: Murray, 2006). Google ebook. [^]

- Grant Bollmer, Inhuman Networks: Social Media and the Archaeology of Connection (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), pp. 30–31. [^]

- See, for example, the work of the CLS Infra consortium in Europe to lift the profile of computational literary studies in the digital humanities by providing training schools, fellowships, and resources to allow individual researchers to make use of available tools. [^]

- When the state of network studies in digital humanities was surveyed in 2017, it was hoped that new strategies would emerge for mainstreaming network analysis in DH. See Micki Kaufman and others, ‘Visualizing Futures of Networks in Digital Humanities Research’, ADHO Proceedings Paper, 2017 <https://dh2017.adho.org/abstracts/428/428.pdf> (p. 2). [^]

- The annotation discussed in this article can be accessed at <https://recogito.pelagios.org/document/4zjsoflcjkqxbe> [accessed 15 February 2023], archived at <https://perma.cc/RSW6-XH9H> (NB text only, linked data not archived). [^]

- See, in particular, ‘Aims & Objectives’ <https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/mappingthelakes/GIS%20Aims.htm> [accessed 24 February 2023], archived at <https://perma.cc/DRP9-YRDU>. [^]

- Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). [^]

- Christopher Donaldson, Ian N. Gregory, and Patricia Murrieta-Flores, ‘Mapping “Wordsworthshire”: A GIS Study of Literary Tourism in Victorian Lakeland’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 20 (2015), 287–307 (p. 307). [^]

- See also, Patricia Murrieta-Flores, Christopher Donaldson, and Ian Gregory, ‘GIS and Literary History: Advancing Digital Humanities Research through the Spatial Analysis of Historical Travel Writing and Topographical Literature’, Digital Humanities Quarterly, 11.1 (2017) <http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/11/1/000283/000283.html#> [accessed 1 October 2023]; and Ian Gregory and others, ‘Geoparsing, GIS, and Textual Analysis: Current Developments in Spatial Humanities Research’, International Journal of Humanities and Arts Computing, 9 (2015), 1–14. [^]

- List of Letters and Tours, Curious Travellers Digital Editions <https://editions.curioustravellers.ac.uk/> [accessed 22 February, 2023]. [^]

- Alex Deans and Nigel Leask, ‘Curious Travellers: Thomas Pennant and the Welsh and Scottish Tour (1760–1820)’, Studies in Scottish Literature, 42 (2016), 164–72 <https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2127&context=ssl> [accessed 3 October 2023 ] (p. 171). [^]

- Ruth Livesey, Writing the Stage Coach Nation: Locality on the Move in Nineteenth-Century British Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 8. [^]

- Aileen Douglas, ‘Time and the Child: The Case of Maria Edgeworth’s Early Lessons’, in Children’s Literature Collections: Approaches to Research, ed. by Keith O’Sullivan and Pádraic Whyte (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 91–105 (p. 94). [^]

- Maria Edgeworth, Harry and Lucy Concluded: Being the Last Part of Early Lessons, 4 vols (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1825), III, 5, 15. [^]

- Dahlia Porter, Science, Form and the Problem of Induction in British Romanticism, Cambridge Studies in Romanticism, 114 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), p. 187. [^]

- Edgeworth, II, 336; Jon Mee, ‘“All that the most romantic imagination could have previously conceived”: Writing an Industrial Revolution 1795 to 1835’, Studies in Romanticism, 61 (2022), 229–54 (p. 231). [^]

- ‘Journal of a Tour from Clapton through North Wales to Ireland’, ed. and intro. by Elizabeth Edwards, in Curious Travellers Digital Editions <https://editions.curioustravellers.ac.uk/doc/0013> [accessed 1 October 2023], archived at <https://perma.cc/8MT8-4STL>. Further references to this edition are given after quotations in the text by folio number (f), recto (r) or verso (v). [^]

- Elizabeth Edwards, Editor’s Introduction, ‘Journal of a Tour’. [^]

- Seán Hewitt and Anna Pilz, ‘Ecologies of the Atlantic Archipelago’, Nineteenth-Century Contexts, 43 (2021), 259–71 (p. 259). [^]

- Isobel Armstrong, ‘Theories of Space and the Nineteenth-Century Novel’, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 17 (2013) <https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.671>. [^]

- Karin Koehler, ‘A Tale of Two Bridges: The Poetry and Politics of Infrastructure in Nineteenth-Century Wales’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 26 (2021), 499–518 (p. 518). [^]

- For more on descriptions of weather, see Marta Werner, ‘The Weather (of) Documents’, ESQ: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture, 62 (2016), 480–529; and Weather, Climate, and the Geographical Imagination: Placing Atmospheric Knowledges, ed. by Martin Mahony and Samuel Randalls (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020). [^]

- Jan Golinski, British Weather and the Climate of Enlightenment (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pp. 6–7. [^]

- See Sally Bushell, Reading and Mapping Fiction: Spatialising the Literary Text (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020). [^]

- See M. M. Bakhtin, The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. by Michael Holquist, trans. by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), pp. 84–258. The concept has been extensively debated since and much used in nineteenth-century literary studies. For a recent summary of the concept and the literature, see Anne De Fina, ‘The Chronotope’, in Handbook of Pragmatics: 25th Annual Instalment, ed. by Frank Brisard and others (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing, 2022), pp. 49–65. [^]

- Tim Edensor, Kaya Barry, and Maria Borovnik, ‘Introduction: Placing Weather’, in Weather: Spaces, Mobilities and Affects, ed. by Kaya Barry, Maria Borovnik, and Tim Edensor (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021), pp. 1–22 (p. 2). [^]

- Andrew Prescott, ‘Made in Sheffield: Industrial Perspectives on the Digital Humanities’, in Proceedings of the Digital Humanities Congress 2012 <https://www.dhi.ac.uk/books/dhc2012/made-in-sheffield/> [accessed 1 October 2023], archived at <https://perma.cc/5R2J-ZYQE>. [^]