Introduction

There are over sixteen thousand grade-listed churches in England and almost every building is unique.1 Over the centuries people have left the marks of their trade in these places, as well as marks of tribute to people and events of the past. Churches embody a rich history, some of which is revealed through the architectural achievements and artistic creativity of craftsmen and craftswomen, seen in the clustered shafts and narrow piers, the decorated capitals, perpendicular traceries, or the colourful stained glass windows. Most of these embellishments were created by professionals formally trained in their crafts. However, a small but nonetheless important contribution was made by individuals who had no previous practical experience of ever having designed or made large-scale architectural objects. Often misconstrued or belittled as ‘mere amateurs’, these untrained men and women were in fact able to create some extraordinary pieces of work. This article will demonstrate some of the achievements this diverse fringe group of amateurs made towards the decorative built ecclesiastical environment in Anglican churches in the nineteenth century, focusing particularly on stained glass windows. It will touch upon the personal endeavours of amateurs, their largely forgotten personal stories, and the legacy they have left behind.

One reason that this matters is that the subject of amateur art and architectural handicrafts in places of worship has not really attracted much attention among social and architectural historians. Early architectural publications such as Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series, which surveyed vast quantities of Anglican churches, are very light on details about the contributions of amateurs and, in many cases, fail to mention this work at all. More recent revised editions, however, are aiming to close this knowledge gap by providing more details about the individual designers and craftspeople and their decorative work. Scholarly essays such as ‘Fashioning Church Interiors: The Importance of Female Amateur Designers’ by Jim Cheshire, which discussed amateur stained glass work by Mary Ellin Miles (1819–1884), or ‘Women and Church Art’ by Lynne Walker, which provided a cross section of amateur artists and their work, including Edith Daubeny’s production of decorative tiles, have certainly helped to challenge the stereotypical assumption that amateurs were eccentric hobbyists or bored middle-class housewives.2 As we shall see, there were a variety of motives for creating amateur stained glass.

Nevertheless, although the last thirty years has seen a steady stream of scholarly literature discussing nineteenth-century ecclesiastical stained glass, the discourse predominantly focuses on material developments, a particular glazing scheme, or any one of the dozens of professional workshops, such as Hardman of Birmingham or the studio of Charles Eamer Kempe.3 Well-known designers such as Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898), who designed for Morris & Co., as well as prolific church architects who demonstrated an interest in stained glass, such as William Burges (1827–1881), also play a great part in the historiography of nineteenth-century ecclesiastical stained glass.4 However, unsurprisingly, little attention, if any, has been directed to the many individual craftsmen who worked in these large workshops and studios, and this can also be said for the small but not insignificant proportion of amateurs, both men and women. These amateurs were untrained non-professionals who designed, and sometimes painted and glazed, their own stained glass windows at their own cost and with little or no help.

It is worth underlining, however, that the notion of the ‘amateur’ was culturally as much as economically determined. While recent research in art history recognizes the different motives of amateur and professional artists, it has also tried to unpick the loaded discourses that placed such a wide gulf between these categories. In a world in which professional, remunerative work was gendered as masculine, and women’s spheres were portrayed as havens from the taint of an ungodly world and the rigours of the capitalistic workplace, contemporaries tended to assume that female artistic creativity was necessarily ‘amateur’, both in its quality and in people’s motivations for pursuing it.5 Put another way, artistic endeavour was fine so long as it was ‘complementary’ to women’s other ‘natural’ domestic duties. There were, then, high hurdles for women to jump if they wished to follow artistic careers. At the same time, however, what defined a ‘profession’ remained fluid and contested, and not only for women. Before the nineteenth century there was a general consensus that ‘the professions’ referred to medicine, religion, and the law, but with the growth of new industries came new spheres of expertise whose practitioners vied for social (and financial) recognition, defining themselves as against their supposedly underqualified or underskilled counterparts.6 Yet not everyone rejoiced in the brisk competence of go-ahead industrial managerialism. William Morris, most famously, championed craft production against mass culture and crass professionalism, but there were also demarcation disputes about what constituted ‘art’ and ‘industry’.7 Amid fears that individual genius was being drowned in a wave of gimcrack imitations, ‘amateur’ could have highly positive connotations, especially when it was construed in terms of personal faith, individual expression, love of art for its own sake, and so on.

As Stephen Knott has recognized, nineteenth-century amateurs have made an important contribution to the material culture of the modern world. He argues that ‘amateur craft […] remains the freest, most autonomous form of making, within structures of Western capitalism at least’.8 Although extant scholarship acknowledges the more localized production of handicrafts in places of Christian worship and hypothesizes about the iconography and its interpretation (particularly when discussing memorial windows), scholars have habitually overlooked amateurs’ inspiration, motivation, and the thought process leading up to the design and the subsequent manufacture of the object. Furthermore, many of the published scholarly resources discussing stained glass seldom examine the objects from a craftsperson’s perspective. It requires a tacit knowledge gained over years working with the material to suggest and make judgements about how many of the unorthodox amateur windows were designed and made, as shall be seen in this article.

While there is much we still do not know about many of the men and women artisans involved in amateur phenomena, it is clear that these serious novice crafters can by no means be categorized as cases of aristocratic eccentricity or isolated feminine seclusion. Quite the opposite is true. The more we find out about individuals who fully immersed themselves in the craft, the more we realize that similar traits were shared by both male and female amateurs, although it appears that the majority of amateurs belonged to the upper classes of society who had sufficient funds to support their endeavours and the luxury of managing their own leisure time. This was a criticism of the nineteenth-century art critic, writer, and artist Harry Quilter (1851–1907), who, in his 1886 essay ‘The Amateur’, protested at how often the upper and middle classes ‘drift […] into some nasty pursuit’, ‘in the endeavour to justify to themselves their own existence’.9 Many amateurs were individuals with strong characters, who had great vision and were determined to succeed in their adventurous endeavours. Significantly, almost all had a close connection to the church in which their work is to be found and a strong Christian faith, which gave them confidence, mental strength, and spiritual guidance.

During more than thirty years working as a stained glass conservator, examining amateur stained glass at close quarters, my research into amateur phenomena has gathered sufficient evidence to suggest that the activity of ‘novices’ producing religious-motivated architectural arts and crafts to embellish a place of worship was not as uncommon as one might at first think. While there is some recognition of individuals having designed or perhaps made one or two objects for a particular place of worship, the overall contribution that non-professional artisans have made towards architectural religious work during the nineteenth century is, on the whole, not yet fully understood. Neither is the effort and determination by which amateurs created highly personalized religious architectural objects. Subconsciously, by creating these items following a head, heart, and hand approach, amateurs were not only directly engaging with their craft but also, more importantly, making a strong statement about their faith, leaving traces that scholars have been slow to investigate, where indeed they have recognized their work at all. This article seeks to remedy that neglect.

Identifying amateur stained glass

In order to measure the extent of amateur activity I have carried out extensive fieldwork, together with spending time in archives and searching through contemporary periodicals such as the Ecclesiologist and the Builder. Creating a comprehensive database together with a location map and several charts, I was able to compare and evaluate all the gathered data to see how widespread the amateur movement actually was and when the trend peaked. Although international colleagues in France, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland were able to point to a few examples, my research highlighted that the amateur phenomenon was quintessentially a British trend. Within England, most of the amateur activity occurred in rural rather than urban areas, and geographically the activities were reasonably wide and evenly spread.

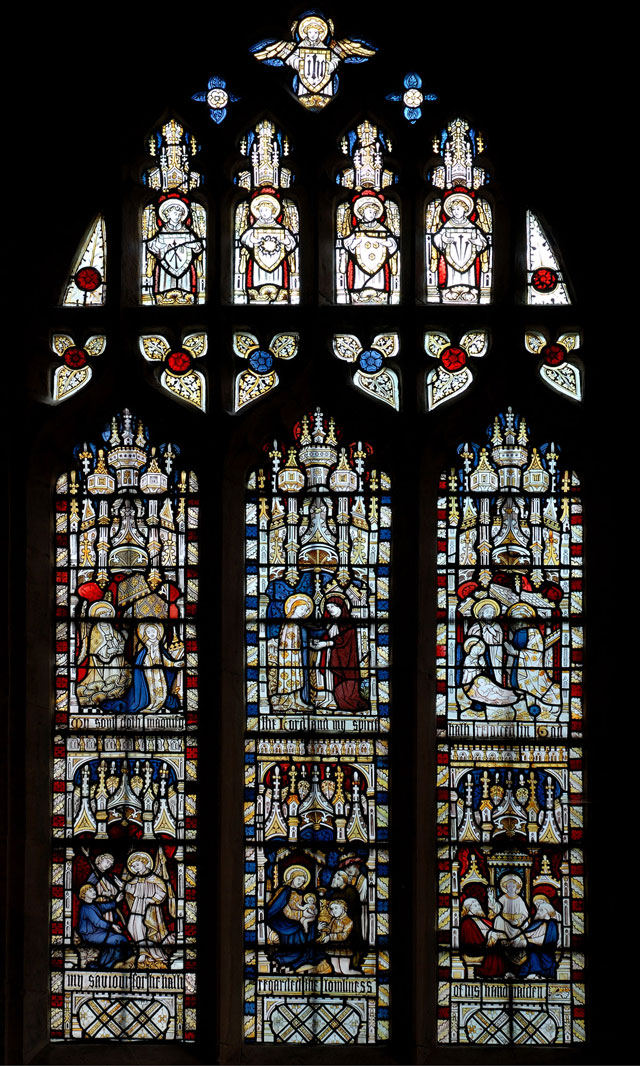

Out of all of the 151 amateurs discovered who produced ecclesiastical crafts during the whole of the nineteenth century, stained glass was by far the most common medium, with forty-two men and forty-two women being equally engaged in the craft.10 Other arts and crafts produced by amateurs primarily for places of Christian worship, especially within Anglican churches and cathedrals, included fixed architectural decoration within ecclesiastical contexts, whether surface decoration such as wall paintings, wood carving on pew ends, stone carving, mosaic, or inlays. Some amateurs only produced one window but others, such as the Sutton brothers, had a more prolific output of over twenty-five full-size lancet windows, including a large five-light west window for Lincoln Cathedral. Another such example is the work of Mrs Letitia Neale Lea (1829–1877), who between 1857 and 1858 painted twenty clerestory windows for St Peter’s, Bournemouth. Together with a group of like-minded women contemporaries, Lea also produced a large five-light window for Surry Hills Church, New South Wales, Australia between June 1857 and July 1858.

Although there are a few amateur windows recorded as having been made during the very early part of the nineteenth century, the research shows that the general trend for amateur stained glass really began quite suddenly in the 1830s and rose steadily during the 1850s, reaching its peak in the 1860s. It is perhaps no coincidence that the rise of the amateur movement occurs almost in parallel with the Gothic Revival influenced by both Tractarian and Ecclesiological ideologies. Government legislation — in particular, the Church Building Acts of 1818 and 1824 — led to hundreds of new Anglican churches being built, which peaked in 1860. Just over one thousand places of worship were consecrated in that year alone. In this era of new church building, the popularity of furnishing church windows with stained glass was ever increasing.

Smaller groups, such as the Society for the Enlargement, Building and Repairing of Churches, also took an interest in funding restoration of church buildings and, as a consequence, many original medieval churches were being repaired and refurnished. With the fast-moving industrialization of the nation, together with changes in the population’s expectations, social and religious patterns changed. This fostered fresh ideas and created opportunities for untrained men and women to engage actively in architectural ecclesiastical ornamentation. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, the amateur movement had dropped quite dramatically and, leading into the twentieth century, amateur engagement with stained glass, like other ecclesiastical arts, continued only on the periphery, being in many ways absorbed into a new DIY culture.

Interestingly, my research also found that in many cases two or more amateurs were operating within the same geographical area, with the individuals belonging either to a similar social group or being of similar age, although not necessarily engaging in the same craft. Circumstantial evidence suggests that amateurs who moved within the same social circles were by and large most likely to share ideas and spark off one another. This is particularly evident among women amateurs and it is individuals in this group who were also most likely to collaborate on projects, even large multiple projects. Besides producing ecclesiastical embellishments, a small number of women amateurs were also involved in other arts, including book illustration. Men, on the other hand, tended to work rather more in isolation and on their own, unless they were involving other family members. Men were also most likely to belong to organizations such as the Associated Architectural Societies and to produce and read papers on their chosen subject during the meetings. Rev. Henry Usher (1817–1896), for instance, who painted the windows for his church at St Clement’s, Saltfleetby, Lincolnshire, presented a paper titled ‘Glass Painting’ to the Lincoln Diocesan Architectural Society in 1871.

Women’s involvement

One of the earliest examples of a nineteenth-century painted window by an amateur is the work of a woman, Sophia Musters (1758–1819). The glass dates from 1817 and the few panels which have survived were once part of the east window at St John’s, Colwick, Nottinghamshire. Musters worked during a transitional period of glass painting and, rather than moving onto the traditional medieval mosaic type of stained glass once again made popular by the Gothic Revival, she followed the tradition of the eighteenth-century enamel-style glass painting. Part of her window included copies of the popular subject of the Virtues, designed by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) for the west window of New College Oxford (1779–85). Close examination of her painted glass undoubtedly suggests she must have had some professional assistance, given the complexity of the multilayering of the enamel paint and the delicateness in the precise firing processes required for these materials. It is also noteworthy that Musters selected unusual religious subject matter for the central scene of her east window, with a depiction of herself as the Virgin Mary closely holding the infant child in the Flight to Egypt inspired by Renaissance painters such as Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682) and Jacopo Tintoretto (1518–1594) (Fig. 1). Musters placed herself in the holy scene as the Virgin Mary and in doing so the Flight to Egypt provided the theme of ‘an escape’, perhaps a reflection of her feelings towards an unhappy marriage during which she was constantly in the public eye.11 Musters died two years after the window was painted.

Whereas men historically saw ‘access to leisure’ as part of their masculine freedom, as Jim Cheshire has argued, the art of handicrafts and making during the nineteenth century provided middle-class women with such access too (p. 79). This statement is directed towards the women who made small mobile decorative objects in the confines of their own homes rather than large-scale ecclesiastical designs, but can also be applied to this context. For women such as Sarah Losh (1785–1853) or Mildred Keyworth Holland (1813–1878), there must have been other, more fundamental reasons for undertaking monumental ecclesiastic work, such as Holland’s painting of a whole chancel and nave ceiling at St Mary’s, Huntingfield, Suffolk, between 1859 and 1866; or the unconventional architectural work of Losh, who in 1841 and 1842 designed and oversaw the construction of a new church at Wreay, Cumbria using design elements and decoration which, according to Simon Jenkins, verge on the ‘Disneyesque’.12 Both women’s activity certainly goes way beyond the matter of ‘access to leisure’ and would suggest greater ambitions and deeper religious motivations. Kyriaki Hadjiafxendi and Patricia Zakreski have noted that, ‘thanks to the campaign for women’s rights’, by the middle of the nineteenth century middle-class women ‘were no longer satisfied pursuing their artistic occupations as enthusiastic amateurs’ in just embellishing their domestic sphere, and they discuss the proliferation of handicrafts moving into the public arena (p. 2). What better public space than the local church? The church was a public place where the woman amateur could exhibit her own handmade object and simultaneously demonstrate her faith. By fixing her art permanently in such a building, the woman amateur challenged the status quo and was also safe in the knowledge that her work was relatively protected from overzealous ridicule by the nation’s critics, who were typically male.13

Women also turned to gendered literature for inspiration. Novels written for female readers had the potential to empower them, perhaps through identification with the central female character in the text. Kate Flint argues that ‘reading itself was a consumption […] of leisure time’ and through reading women were stimulated in ‘their […] capacity for self-awareness and social analysis and judgement’.14 Literature written by women for women, in particular, did much for the liberation of the upper- and middle-class female population, who saw an opportunity to master more intelligent, challenging, and complex ways of expressing themselves. Economic changes, too, combined with a striving for social equality and debates about female creativity outside the home to open up new mental and cultural spaces for self-expression. As Lynne Walker has underlined, this ‘included the demands for paid employment, training, education and access to the professions’ (p. 122).

Jane Hamlett provides an interesting observation regarding the gendered domestic space within the home, where women tended to produce major architectural handiwork. The study of ‘material culture’, she argues, is ‘a matter of understanding of objects which can reveal the core values of a society’.15 For women to engage in genteel handicrafts such as embroidery, drawing, or creating decorative objects for the home, the intimacy and privacy of the morning room would have often sufficed as a suitable and morally acceptable creative space. However, providing socially acceptable space so as to construct large architectural objects such as stained glass windows was a different matter entirely and it would have tested even the most liberal of Victorian households. As Birkin Haward observes, the processes of making stained glass were not easily achieved in the confines of one’s own home:

The stained glass craft is one which can be learned by an individual and carried out on a small scale. Of the tasks of designing, cutting glass, painting, firing, leading up and fixing in the opening, the latter three tasks, and in particular the building and operating of a suitable kiln, are the most difficult for an amateur, but if necessary these parts of the work can be sublet to an established firm.16

The practicalities of making

The examination of surviving account and day books of professional stained glass workshops reveals that amateurs quite regularly approached glaziers in order to purchase tools and materials, receive practical help, or have parts of the more technical work carried out by professionals. For instance, the accounts of the London firm James Powell & Sons (now in the National Art Library) reveal several entries where amateurs regularly bought materials for their stained glass endeavours. One such entry lists the amateur glass painter and maker Rev. William Willimott (1825–1899). Willimott seems to have cut, painted, fired, and glazed his own stained glass windows. During November 1864 and November 1878, he features a number of times in Powell’s accounts when he ordered several consignments of lead cames, sheets of glass, bottles of silver stain, and on one occasion a 2 oz bottle of fluoric acid. The goods were all delivered to the rectory of St Michael Caerhays, Cornwall and, during Willimott’s 26-year incumbency, he produced an astonishing number of complex windows for Cornish churches at St Michael and All Angels, Caerhays, St Hugh at Quethiock, and St Kea, Old Kea.

The purchase of materials by amateurs from large studios was not uncommon. In the account books of another studio, Joseph Bell & Son, Bristol, an amateur named Mary Ellin Miles from Bingham in Nottinghamshire appears several times. Miles was the wife of the incumbent of All Saints’ Church, Bingham and, between 1848 and 1854, she painted several windows for the church, purchasing quantities of spike, oil, brown stencil, and camel-hair brushes. Unlike Willimott, who cut, painted, fired, and glazed his windows, the accounts show that Miles commissioned all the manual labour of cutting, burning, and leading the glass from the professional studio, while she concentrated her efforts on designing and painting the windows.

By the late 1850s large studios such as Heaton and Butler recognized the rise of the amateur movement and the firm devoted a small section to ‘Amateur Glass Staining’ in their Illustrated Catalogue of Stained Glass Windows, which served as an advertisement as well as a catalogue. The firm identified the amateur as a potentially lucrative niche market and the catalogue not only provided hints and observations to the novice makers but also offered their services by carrying out the various manual processes and supplying tools and materials needed for the successful production of one’s own stained glass window.

Contemporary newspapers also reveal that local stained glass firms offered their assistance to amateurs. A classified advertisement placed in the Brighton Gazette in December 1864 reads:

An artist in stained glass is desirous of instructing a few pupils (ladies or gentlemen, residing at or near Brighton) in the Art of Painting upon Glass, with a view to enable them to execute a window for a Church, either as memorial or otherwise.17

Amateurs could also read up on the history, techniques, and processes of stained glass from the many published sources on the subject in journals and periodicals, some specifically aimed at and authored by amateurs, while others were more general authorities on the process of glassmaking.18 There even appeared to have been a Society of Amateur Glass Painters by the end of the 1850s, which placed a stained glass window (now lost) in Holy Trinity, Springfield, Essex.19

The unorthodox approaches of the amateur

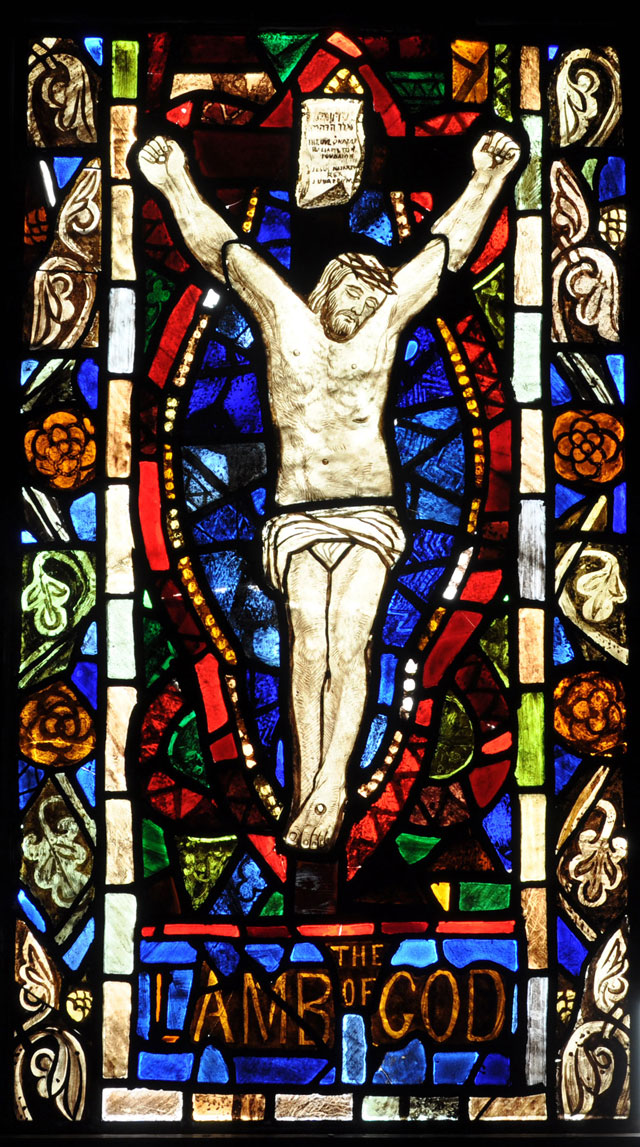

Working under the guidance of a professional’s studio was one of the options amateurs might choose to complete their work. However, as soon as the amateur worked on their own and in isolation the end results could become very interesting, ranging from innovative to totally unorthodox. When the new church of St Mark’s, Lincoln was built in 1872, the Rev. James Mansell (1837–1899) managed to place a couple of his own windows into his newly erected church (Fig. 2). Inspired by careful observations examining medieval windows, Mansell recreated the visual faults of medieval glass, owing to the ageing process and subsequent deterioration of the material, to replicate these aesthetics. With this in mind, he applied techniques such as corrosion painting, applying dark, dirty mattings, and glazing the work using additional strap and repair leads in order to achieve an authentically ‘aged’ look for his brand-new windows. His amateur approach was also evident in his working methods. On close examination of the glass one can actually see the identification numbers, which he had painted onto it, and his fingerprints, which have been captured in the paint before it was permanently fixed. On careful observation, this window looks crudely painted, overfired, and untidily glazed and it is a wonder that the object has survived at all. However, Mansell had clearly looked closely at medieval windows and realized that the lead work, glass, and vitreous paint are materials that can be manipulated to achieve desired effects. Mansell lived in Vicars’ Court, close to Lincoln Cathedral with its amazing collection of medieval stained glass. If he could not have a genuine medieval window in his own church, why not paint one himself that appeared medieval? His approach to glass painting is absolutely unique among amateurs. It appears that Mansell only produced two windows for his church and when in July 1872 St Mark’s was consecrated, the subsequent building inspection by the Associated Architectural Societies’ Committee remarked upon his windows: ‘The modern glass in the east window is of rich general effect; but the figure of Our Lord on the Cross is disagreeably dirty.’20 Although critiques mostly acknowledged the ‘charming work’ produced by amateurs, amateurs did not always escape the rigour of professional censorship by the Ecclesiological Society or local architectural societies just because they were members of the Church of England or belonged to the upper classes.

While some amateurs worked only in one craft, others tried their hand with multiple media. Jane Anne Nelson (1829–1900), the daughter of a vicar, and a farmer’s wife, painted several windows for the parish churches of St Mary at Holme-next-the-Sea and St Andrew at Barton Bendish, Norfolk. The three-light east window at Barton Bendish dates from c. 1880 and carries the popular theme of the Ascension (Fig. 3). The window is extremely rich, using a colourful palette of glass. The multiple figures are arranged in a tight space and, although the facial features are quite expressive, they are sketchily painted, somewhat akin to a pencil drawing or a watercolour. Some of the perspective is also wrong and there seems to be a rather tangled mess of wings with angels being placed in a very small space. On either side of the east window are a couple of wall hangings depicting the four evangelists drawn on stretched linen, also by Nelson (Figs. 4, 5). The figures appear out of proportion compared to those she painted in the window and, looking closer at the artwork of the wall hangings, we can observe that Nelson drew the outlines of the figures in pencil first before filling in the details in colour. These artworks fascinatingly capture Nelson’s approach to, and skill working in, two very different media. It seems that the work was abandoned halfway through and Nelson never quite finished it. Following her through the various stages of her work, it is as if she had momentarily laid down her tools only to come back to finish the murals later.

The nineteenth-century stained glass amateur was a product of his or her own social and religious environment and had little recognition of their own ineptness as far as the craft is concerned. In fact, some amateurs had a rather charming style because they created in a self-expressive manner, producing crafts and art in what mattered to them. Amateur windows are often seen as oddities and curiosities and can be misunderstood as bad art or bad craftsmanship. But what constitutes the distinction between good (professional) art and bad (amateur) art in a stained glass window; and does it really matter in the eyes of the amateur?

Essentially, coloured glass provides a canvas on which to paint images and narratives often incorporating religious iconography and personal messages. With the amateur as the communicator and the glass as the interface it is not the professional finish of the object that is deemed most important but the message that the novice artist wanted to convey or demonstrate with their handiwork. What is it that drives the human spirit to endeavour in a ‘spiritually, emotionally, and physically demanding work of bringing new objects into the world with creativity and skill?’, asks Peter Korn.21 And, specifically, what motivated the nineteenth-century amateur to pick up the necessary tools and engage in designing and crafting religious stained glass?

Stained glass is a craft that enables the craftsperson to set off on a journey of discovery of one’s own ability, creativity, and self-transformation. What professional and amateur crafters have in common is that they both begin with the same intention, the desire to design and make a window or, as Richard Sennett defines it, ‘the desire to do something well for its own sake’.22 Both can end up solving problems as they occur along the way, although the professional will undoubtedly be better equipped to do this, with a more developed skill set and more specialist tools to hand. The professional will have all the advantages of having had some kind of formal training by one or a group of senior craftspeople, and the trainee professional will then go on to find his or her niche and own method of doing things. They are on a continuous path of learning, and on their journey the professional will be influenced by arguments, judgements, styles, developments, experience, and, most of all, their own acquired self-criticism. The amateur, on the other hand, will have none of these advantages. In fact, to the amateur such disadvantages may be seen as advantages, in having no one to please but themselves and in not having to conform to professional standards or production pressures.

Memory making

The catalyst for the individual amateur to be involved in architectural religious decoration within a church is often undocumented, and there is no single explanation why it happened. The Gothic Revival, social changes, the availability of funds and leisure time, and a great interest in religion and architecture must have all played a vital part. Possibly one of the most important explanations for amateurs being involved in making their own stained glass windows is the rise of memory making. In the years that followed the death of Prince Albert in 1861, Queen Victoria found it difficult to accept her loss and in her extensive grieving undoubtedly perpetuated the already popular fashion of commemorating the departed through various kinds of material culture. Jane Hamlett highlights that this Victorian trend of commemorating the dead was often reflected in the display of religiously motivated objects around the house or in elaborate funerals and burial practices.23 She goes on to say that ‘sociologists have emphasized that the active role of objects combined with social practices were an important feature in producing memories and that female expressions of memories of the dead in the domestic sphere have been largely overlooked’ (p. 181). What has also been overlooked was the placing of large personal handcrafted architectural funeral memorials such as stained glass windows in places of worship.24 The importance of the involvement of producing one’s own commemorative set of painted windows can perhaps be measured in the work of Louisa Charlotte Hobart (1826–1909). Hobart produced only a limited quantity of windows but her sketches show the gradual intellectual evolution of her art, starting with a number of pencil drawings, and leading to the subsequent production of several small watercolour designs for her stained glass windows (Fig. 6).25

Hobart’s work is not necessarily unique among women amateur stained glass designers but what makes her windows stand out is the exceptionally personal and intimate nature of her three memorial windows. When looking at her painted glass for the church of All Saints, Nocton, Lincolnshire (Fig. 7), some of which was painted with the assistance of Ward & Hughes, one can read the intimacy in her design and how the artist connected with the subject in reflecting her personal bereavement and the closeness to her two deceased sisters and her baby niece. Hobart’s work shows that amateur windows can contain very personalized messages and symbolism which are known only to close family members, and therefore some windows can be hard to read, making the narrative and interpretation of such elements very exclusive. The iconography in her designs, and particularly that of the two windows at St Nicholas, Fulbeck, Lincolnshire, focuses strongly on the women of the Christian narrative. This is perhaps an example of how Victorian artists gravitated towards ‘Madonnas and Magdalenes’, either in a literal or figurative sense, as articulating particular notions of female piety or repentance.26

Some of the most ostentatious of all memory making is the work of Cecil George Savile Foljambe, 1st Earl of Liverpool (1846–1907). Foljambe managed to build up a working relationship with one of the leading nineteenth-century stained glass studios, Heaton, Butler & Bayne. When his first wife Louise Blanche died in 1871, for the next thirty-six years Foljambe erected memorial plaques and windows in her memory in dozens of churches across Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. This is a typical example of the Victorian upper and middle classes’ ostentatious attitude to commemorating the dead. Foljambe designed and painted some of these windows himself. For instance, the east window at St Giles’ Church, Ollerton, Nottinghamshire, depicts scenes of the Crucifixion, Entombment, and Resurrection of Christ, with miracles of Christ raising the dead to life below. A commemorative inscription below documents his work and his beloved wife.

The professional amateur

Many of the amateurs uncovered during my research played just a minor part in the historiography of stained glass. Examples of such individuals are Lydia Frances Banks Wright (1831–1892), who in 1863 painted two windows for her father’s church of St Mary and all Angels’, Shelton, Nottinghamshire; or the work of Miss Lucy Rickards (1822–1863), who designed, painted, fired, and glazed six very tall nave windows in 1846 for St George’s, Stowlangtoft, Suffolk. Another is Mrs Ann Owen (1817–1892), who designed and painted nine pictorial medallions representing the miracles and episodes of the life of Christ for St Margaret’s, Heveningham, Suffolk; and Miss Dorothea Cripps (1827–1914), who painted a two-light window including a quatrefoil tracery in 1861 in memory of her father for All Saints’, Preston, Gloucestershire.

Many of the gentlemen amateurs who tried their hand in the art and craft of stained glass were usually associated with the church, often being the incumbent or the patron: for example, the Rev. Charles Pierrepoint Cleaver-Peach (1829–1886), who in 1871 painted the east window and carved the pulpit and pew ends for St Helen’s, Amotherby, Yorkshire; or the Rev. Joseph Holdon Johnson (1792–1884), who in 1846 reordered and painted a number of new windows for St Thomas à Becket, Tilshead, Wiltshire. As already mentioned, the work by men was subtly different to that of women amateurs. While women were most likely to work with other like-minded contemporaries on a single project, men tended to work on their own and on a larger scale in terms of volume and reach, placing windows in more than one church. We have already heard about the extensive work of William Willimott for churches in Cornwall, but also worth a mention is the work by Rev. Henry Usher, who painted several windows for churches in Gloucestershire and Lincolnshire, or the work of Rev. Arthur Moore (1804–1852) rector of Walpole St Peter, Norfolk who designed, painted, and presented several windows for Ely Cathedral.

Possibly two of the most prolific of all stained glass amateurs to emerge during the mid-nineteenth century were the Sutton brothers: Rev. Augustus (1825–1885) and Rev. Frederick Heathcote (1833–1888). Between them they produced more than forty-five windows in several churches in Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire, Norfolk, and Lincoln Cathedral. They undoubtedly were the archetypical ‘professional amateurs’ of the Victorian era. Sons of Sir Richard Sutton II (1799–1855), baronet of Norwood Park in Nottinghamshire, Augustus and Frederick enjoyed a privileged and very wealthy upbringing. Both sons were educated at Eton and Cambridge, and both followed the lead set by the Cambridge Camden Society, being instrumental in church decoration among their ecclesiastical peers. Working together with influential architects such as George Frederick Bodley (1827–1907), Frederick Sutton, in particular, was engaged in several ecclesiastical refurbishments.27 The Suttons were clearly well connected, although many questions surrounding their work remain unanswered. Where, for example, were the twenty-nine windows for Lincoln Cathedral made and where did the materials come from? And most importantly, who paid for all this?

The Suttons’ use of iconography within their windows is rather interesting, especially in their early work. Influenced by medieval traditions, and especially an Early English style, their windows often depicted biblical subject matter using only single figures or small groupings. There was little room for the fancy ornamentation and complex architectural backgrounds characteristic of the professional workshops of the mid-nineteenth century. By 1860 fashions were moving still further in that direction and Pre-Raphaelitism, with its rich ornamentation, dramatic backdrops, and intricate architectural arrangements, was steadily filtering into stained glass. The Suttons ignored all of this, focusing instead on bold, plain, primary-coloured medieval designs, and eschewing the use of silver stain in their work in order to create highlights or to hint at dimension or perspective. In fact, delicacy and refinement in their figurative designs, glass cutting, and painted work were rather rare, particularly in their early work.

Frederick Sutton went on to work with Bodley and the stained glass studio of Charles Eamer Kempe (1837–1907), from whom he learned to adjust his glass painting style. Subsequently, this led Sutton to change his designs, bringing them closer to the style of the late fourteenth century. Compared with other amateurs, Sutton produced enough work during his lifetime over a significant period to set himself on a path of learning, and one can recognize an improvement in his later work. This is especially apparent in one project. Being appointed vicar of St Helen’s at Brant Broughton in Lincolnshire in 1873, which stood on his father’s country estate, Frederick Sutton immediately set upon restoring the medieval church (Fig. 8). All the work here is well documented in his own handwritten restoration diary, which still exists at the church, and contains Sutton’s drawings and ideas. Together with Bodley, Sutton created here a coherent piece of architectural ecclesiastical art where all artistic elements of metalwork, stained glass, floor covering, altar cloth, wall decoration, and the organ casement fitted neatly together. This was a place where the novice evolved into a professional amateur in order to create a total work of ecclesiastical art.

Clearly, the Suttons were an unusual example of amateurs who were treated as borderline professionals, and who certainly worked closely with leading professionals. Their influence was also widely acknowledged at the time. The precentor of Lincoln Cathedral’s tribute to Frederick Sutton acknowledged that

in architecture, painting, sculpture, music, glass-painting, wood carving, metal work, organ building, enamels, illuminations — in short, in everything in which art lends itself as a handmaid to religion, Mr. Sutton’s knowledge was as wide and accurate as his taste was refined and his judgement sound.28

This was echoed by one of the leading architects of the time who said that ‘if Sutton had not entered the ministry but followed architecture as a profession in his opinion, he would have secured a position of highest distinction in Europe’ (Davidson, p. 7).

Conclusion

The individuals mentioned in this article are only a small selection of the amateurs who worked in stained glass with wide-ranging approaches, styles, and social circles. The examples cited give us a sense of who some of these people were, and reveal their varying backgrounds, motivations, and, of course, their immense diversity and level of skill. For the most part overlooked by architectural, social, and stained glass historians, nineteenth-century amateurs and the homemade objects they produced are an important part of our social, material, and cultural history.

What connects all of these amateur windows, or indeed any other ecclesiastical amateur crafted objects, is that they have been motivated by faith, personal events, and an appreciation of craft, but also by a curiosity and desire to make things with one’s own hands that would embellish the place one worshipped in. Interestingly, unlike many of the professional stained glass studios, which relied merely on their house style as a mark of identification, most amateurs, including Musters and Hobart, actually marked, dated, and signed their work, which suggests that amateurs were keen to have some sort of recognition of their artistic endeavour.

One has to admit that, aesthetically and materially, amateur stained glass windows have a life of their own, with a certain kind of naivety and homemade charm. I guess if stained glass could have a soul, these windows would certainly have one, and yes, to some purist stained glass connoisseurs perhaps they are the bad and the ugly! But although they are unlike the many professionally designed and perfectly crafted windows we see in churches up and down the country, amateur windows cannot be dismissed as simply quirky decorative religious objects made by eccentric vicars or lonely spinsters. They offer us a rare glimpse into a corner of Victorian visual and material culture of which we still know very little. Often they provide more personal as well as material insights into the interrelated issues of faith, memory, and making, and there are many more stories yet to be discovered and told.

Notes

- Church of England, ‘Launch of Major New Report’, 13 October 2015 <https://www.churchofengland.org/more/media-centre/news/launch-major-new-report-how-church-england-manages-its-16000-church> [accessed 21 March 2020]. [^]

- Jim Cheshire, ‘Fashioning Church Interiors: The Importance of Female Amateur Designers’, in Material Religion in Modern Britain: The Spirit of Things, ed. by Timothy Willem Jones and Lucinda Matthews-Jones (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 77–99; Lynne Walker, ‘Women and Church Art’, in Churches 1870–1914, ed. by Teresa Sladen and Andrew Saint, Studies in Victorian Architecture and Design, 3 (London: Victorian Society, 2011), pp. 121–43. [^]

- Stanley A. Shepherd, The Stained Glass of A. W. N. Pugin (Reading: Spire, 2009); Adrian Barlow, The Life, Art and Legacy of Charles Eamer Kempe (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press, 2018). [^]

- See, for example, J. Mordaunt Crook, William Burges and the High Victorian Dream (London: Murray, 1981). [^]

- See, for example, Francina Irwin, ‘Amusement or Instruction? Watercolour Manuals and the Woman Amateur’, in Women in the Victorian Art World, ed. by Clarissa Campbell Orr (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), pp. 149–66. [^]

- Kyriaki Hadjiafxendi and Patricia Zakreski, ‘Introduction: Artistry and Industry — The Process of Female Professionalisation’, in Crafting the Woman Professional in the Long Nineteenth Century: Artistry and Industry in Britain, ed. by Kyriaki Hadjiafxendi and Patricia Zakreski (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), pp. 1–22 (pp. 1–2). [^]

- Art versus Industry?: New Perspectives on Visual and Industrial Cultures in Nineteenth-Century Britain, ed. by Kate Nichols, Rebecca Wade, and Gabriel Williams (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016). [^]

- Stephen Knott, Amateur Craft: History and Theory (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), p. xi. [^]

- Harry Quilter, ‘The Amateur’, Contemporary Review, March 1886, pp. 383–402 (p. 383). [^]

- Numbers constantly fluctuate with new amateurs being discovered and others being removed, but on the whole the trend has stayed fairly gender balanced. [^]

- Charles Howard Hodges after Sir Joshua Reynolds, Mrs Musters as Hebe, 1785 <https://www.york.ac.uk/history-of-art/virtual-exhibition/thegeorgianface/22.html> [accessed 26 March 2020]. [^]

- Simon Knott, ‘St Mary, Huntingfield’, April 2019 <http://www.suffolkchurches.co.uk/huntingfield.htm> [accessed 26 March 2020]; Simon Jenkins, England’s Thousand Best Churches (London: Penguin, 2000), p. 103. [^]

- Louisa Anne Beresford, Marchioness of Waterford (1818–1891) designed several stained glass windows and also a large set of ecclesiastical mural paintings on canvas for Ford village school, in Northumberland. John Ruskin became a great acquaintance of Beresford but she could not depend on him for encouragement. In fact, he was constantly criticizing her monumental amateur work: ‘Even before he had seen her murals Ruskin told Beresford that she was wasting her talents.’ See Robert Franklin, Lady Waterford, Artist and Philanthropist (Brighton: Book Guild, 2011), p. 98. [^]

- Kate Flint, The Woman Reader, 1837–1914 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), pp. 11, 15. [^]

- Jane Hamlett, Material Relations: Domestic Interiors and Middle-Class Families in England, 1850–1910 (Manchester: Manchester University, 2010), p. 10. [^]

- Birkin Haward, Nineteenth-Century Suffolk Stained Glass: Gazetteer, Directory, an Account of Suffolk Stained Glass Painters (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1989), p. 286. [^]

- Classified advertisement, Brighton Gazette, 15 December 1864, p. 4. [^]

- For example, the 1847 works of Charles Winston, a solicitor by profession and a self-proclaimed stained glass amateur; and E. C. Hancock, The Amateur Pottery & Glass Painter (London: Chapman and Hall, 1876). Authoritative glass texts include Emanuel Otto Fromberg, An Essay on the Art of Painting on Glass (London: Weale, 1851); Dr M. A. Gessert, Rudimentary Treatise on the Art of Painting on Glass, or Glass-Staining, 3rd edn (London: Weale, 1857); William Warrington, The History of Stained Glass (London: the author, 1848); and G. R. Porter, Treatise on the Origin, Progressive Improvement, and Present State of the Manufacture of Porcelain and Glass (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown & Green, 1832). [^]

- Haward, p. 286. Haward notes that there is a reference suggesting such a society may have existed (‘Stained Glass’, Builder, 3 January 1857, p. 10). This refers to a window (now lost) by a member of Holy Trinity, Springfield, Essex, but no information has been found to indicate whether the organization referred to was a national body or a local society. [^]

- ‘The Twenty-Ninth Report of the Lincoln Diocesan Architectural Society’, in Associated Architectural Societies’ Reports and Papers, IX, Part 2 (1872), pp. lxxiii–lxxxvi (p. lxxxv). [^]

- Peter Korn, Why We Make Things and Why It Matters: The Education of a Craftsman (London: Square Peg, 2015), p. 7. [^]

- Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (London: Allen Lane, 2008), p. 9. [^]

- Hamlett, pp. 181–85. See also, Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014). [^]

- On stained glass memorial windows, see Michael Kerney, ‘The Victorian Memorial Window’, Journal of Stained Glass, 31 (2007), 66–94. [^]

- Drawing and design notes are deposited in the Lincolnshire Archives, Lincoln, Nocton Par9/1: Drawing book. [^]

- Kimberly VanEsveld Adams, Our Lady of Victorian Feminism: The Madonna in the Work of Anna Jameson, Margaret Fuller, and George Eliot (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2001), p. 5. [^]

- On Sutton and Bodley, see Michael Hall, George Frederick Bodley and the Later Gothic Revival in Britain and America (London: Yale University Press, 2014). [^]

- Canon Hilary Davidson, ‘Introduction’, in Frederick Heathcote Sutton, Church Organs: Their Position and Construction, 3rd edn (London: Rivingtons, 1883; repr. Oxford: Positif Press, 1998, intro. by Canon Hilary Davidson), pp. 7–9 (p. 7). [^]