Nineteenth-century Britain saw an explosion in the use of decorative glazing. The enormous impact and significance of decorative glass produced for the palaces of commerce and recreation in cities and towns throughout Britain has been largely overlooked. Previous studies of British stained glass of this period have focused almost exclusively on ecclesiastical settings and the oeuvre of individual artists or firms.1 Specialist studies of building types also overlook their decorative glazing. Secular decorative glazing has recently received brief scholarly attention, but its importance in the wider social, cultural, and industrial context has yet to be studied.2 Secular glazing is, in short, a much understudied field of research, although it was widely used in industrial and commercial buildings such as town halls, public houses, and shops to define space and illustrate the functions of these buildings.

The Rochdale Library, Museum, and Art Gallery building, collectively now known as Touchstones Rochdale, is an excellent showcase of the development and use of secular stained glass throughout the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It is a prime example of a secular building containing stained glass that would normally be overlooked.3 The glazing scheme at Touchstones, although now incomplete, is an example of how stained glass used modern materials to articulate space, gender, and class in ways that were ubiquitous in nineteenth-century culture. It also serves to underline local dynamics and preferences that have often been neglected in explorations of more national and metropolitan-centred trends. The building was originally opened as a public library in 1884 as a stand-alone structure and was extended twice to provide museum and gallery space: the second phase was opened in 1903 and the third phase was completed in 1913. The stained glass in the Free Library, now removed, contained portraiture of well-known male and female authors and the glass from the second phase of development contained symbolic representations of the elements and the countries of the Union. The 1913 extension is not covered in this article but was designed by C. J. Allen (1862–1956) and incorporated additional museum space and two further galleries.

The glass will be discussed by theme, referring to changing aesthetics, starting with the narrative glass depicting portraiture in the old library from 1884 and then the symbolic glass in the 1903 phase.4 The portraiture in the public library, while an excellent representation of civic pride and the influence of donors, was also extraordinary in its reflection of the achievements of women in the arts and sciences, as well as in its representation of regional interests. The stained glass from the second stage of the building reflects new stylistic influences such as art nouveau and symbolically references achievements in the sciences. The glazing reflects developments in aesthetics and glass technology in the later part of the century: in particular, it uses the inherent qualities of the materials to delineate form. The combination of mouth-blown and machine-made glasses used in the schemes reveals new ways of thinking about glass in architecture of the period and underlines the importance of stained glass as a relevant and challenging contemporary art form.

James Ogden and Rochdale Free Library, 1884

Rochdale, now part of Greater Manchester, boasts an illustrious list of political pioneers and instigators of social change. It had a strong sense of its own past and the town and its people were shaped by a prevailing Liberal view in which community pride and progress were uppermost.5 In 1844 Rochdale was the birthplace of the Cooperative movement, founded by the Rochdale Pioneers, who aimed to provide better standards of living for the lower classes in response to the desperate working and living conditions of the Industrial Revolution. The principles of the ‘Co-op’ were adopted internationally and had far-reaching effects. The radical and Liberal politician John Bright (1811–1889), co-founder of the Anti-Corn Law League and free trade advocate, was born in Rochdale.

Rochdale was a booming industrial town in the nineteenth century and the prestige and enormous wealth this brought is demonstrated by its impressive architecture, including the magnificent neo-Gothic Town Hall designed by William Henry Crossland (1835–1908), with the tower redesigned by Alfred Waterhouse (1830–1905) after a disastrous fire in 1883. Rochdale Town Hall contains an extensive and impressive stained glass scheme, with the kings and queens of England in the Great Hall, from the reign of William I up to Queen Victoria, and spectacular renderings of the coats of arms of towns and cities in Britain and worldwide on the staircase. The scheme was designed and manufactured by Heaton, Butler & Bayne of London.

Rochdale Free Library was opened on 30 October 1884. It was designed by Jesse Horsfall (1859–1910), made of Yorkshire stone, and constructed by T. Berry and Son of Milnrow Road, Rochdale.6 The library had previously been based at the town hall, until arrangements were made after the fire for the removal of the books to the new library. An old photograph of the building reveals that it was originally surrounded by housing and mills, showing that the library was at the heart of the community (Fig. 1).

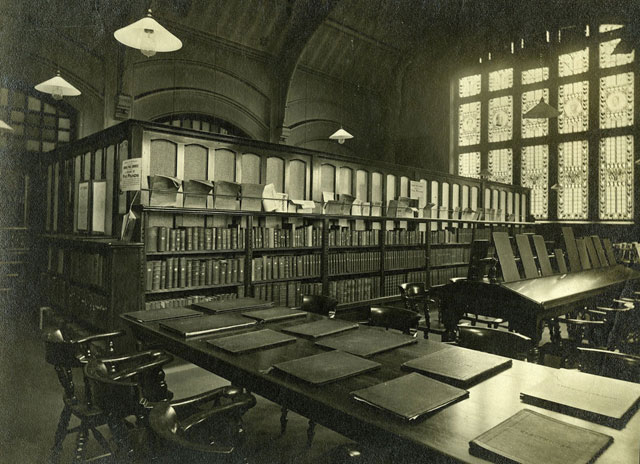

Most of the original decorative glazing in the reading rooms was removed in 1955 and replaced with plain glazing, when alterations to the interior were made in order to allow more light into the lending section (‘Our Heritage’, p. 13). Only one large quatrefoil of the scheme, containing the arms of Rochdale, remains above the original doorway. Fortunately, several good quality photographs taken in the early twentieth century survive which reveal the content of the windows (Figs. 2, 3). There are also informative descriptions in local newspapers of the opening ceremony of the library. They reveal careful consideration of subject matter, as well as the personal tastes and preferences of the donor, James Ogden (1832–1907).

Ogden was another of Rochdale’s influential men. He was a member of Rochdale Town Council representing Castleton East ward until 1891. His political affiliation was with the Tories and, significantly, he was a member of the council’s library committee and made generous benefactions throughout his life to the town of Rochdale. He was known to some in the town as an eccentric character, and he never allowed himself to be photographed.7 Only one painted portrait survives in the Rochdale Art Gallery collection. He was educated locally and entered into his uncle and father’s business as a cabinet maker, until he received a generous bequest which allowed him to live by his own means.8 Ogden was a lover of both art and his town, setting up a fund which still enables the gallery to purchase works today, ‘not to be shut up in rich men’s houses, but to be hung in the people’s galleries’.9 This benevolence was noted by others, with one commentator remarking:

[He believed that] the poor should have free access to all avenues of intellectual advancement. And whether he learned it at the feet of [John] Ruskin, or absorbed the truth as he gazed on the great achievements of mediaeval craftsmen, he knows that labour dissociated from art is debasing, and that appreciation of the beautiful will increase the sum of happiness among the poor as well as among the rich. (‘Local Men of Mark’, p. 6)

Ogden’s wealth allowed him to travel and absorb the artistic and cultural riches of Europe, and he brought his knowledge back to the people of Rochdale. The decorative glass in the library is one example: the windows were originally supposed to be only of clear, plain glass, but Ogden’s donation enabled decorative glass to be used which was harmonious to the space.10 The glass intrinsically changed the experience of the interior and the relationship of the user to the space, as well as acting as a blind to control the light.

Stained glass, space, and gender

The two main, large windows containing portraits of male and female authors, which can be considered a pair, were situated at the south-facing sides of the library reading rooms. This approach reflects a complex interplay of intention and outcome as, despite this apparent equality, the spaces in which they were contained were divided by gender. The rooms were bisected by a central corridor which led off the front doorway, with the principal reading room to the right. This was the men’s reading room and reference department, measuring a lofty twenty-four feet from the floor to the apex of the ceiling.11

The interior of the old library is now somewhat changed: the men’s general reading room still serves as the local studies library, so a sense of the space as it was originally used can be gained, although there is now a mezzanine floor running the length of one bay beside the original window opening. Old photographs of the interior show men reading on long tables, bathed in the light beaming through the decorative glass. The carved wooden beams of the roof, the ornately patterned ceiling grids, and the walls have now been painted white, but the iron supports in the beams and their bolts can clearly be seen. This is a modern, industrial Gothic structure which reinterprets traditional formats found in churches for a secular setting.

Each of the two five-light windows had four mullions and two transoms: a portrait within a medallion of a chosen literary figure sits within the middle sections. Those represented in the men’s reading room were considered some of the greatest male poets and writers of the English language: reading from left to right, Spenser, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, and Wordsworth.12 Decorative floral motifs run the length of the windows and surround the portraits.

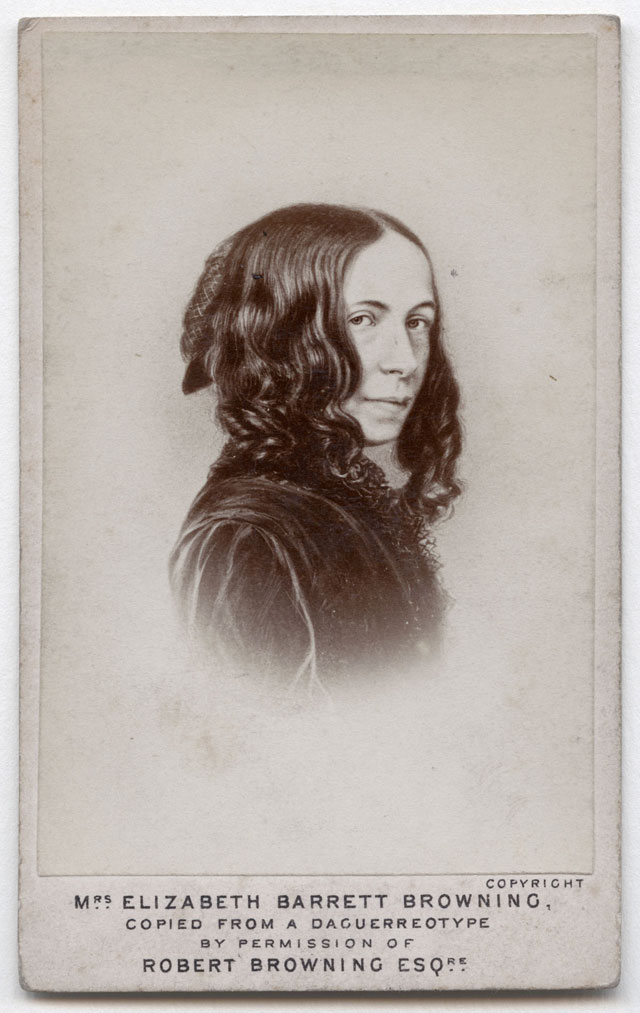

The section of the building to the left of the old entranceway now serves as the permanent museum, but was the original women’s reading room. The room contained an impressive principal window depicting eminent female writers and is notable for many reasons. The window was particularly emphasized in the minutes of the library committee in 1885, which states that it typified ‘the universality and greatness of the genius of woman in Literature during the Victorian era’.13 The selection of portraits is fascinating and Ogden’s decision to request a window depicting female authors allows women equal stature and importance during a time when this was unusual. We would expect to find women depicted in a window that was designated female space, yet it is the celebration of education and learning which makes this a daring step for a space devoted to women. All the women represented were prominent in a particular branch of literature: novelist George Eliot (1819–1880); poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806–1861); scientist and polymath Mary Somerville (1780–1872); art critic Anna Jameson (1794–1860); and Charlotte Brontë (1816–1855), also representing the novel.14 All these were recent, modern authors and innovators in their respective fields, and their portraits would have been inspirational to the women readers who used the space.

The portraits in the windows are all based on popular images of those represented, either in drawings or early photographic images, and are painted in a dark pigment for the outline and shading. The prominent representation of novelists confirms the genre’s significance, and the use of images based on early photographic methods also marks technical innovations of the nineteenth century. George Richmond’s famous portrait of Brontë is visible in the far-left light, with Barrett Browning to her right. Barrett Browning’s portrait is based on a daguerreotype by Elliott & Fry, after Macaire, and dates from 1858 (Fig. 4). Eliot takes centre stage, with her image based on the well-known chalk drawing by Sir Frederic William Burton (1816–1900), dating from 1865. Jameson is to her immediate right and this portrait may be from a calotype of c. 1843–48 by David Octavius Hill (1802–1870) and Robert Adamson (1821–1848). Jameson is followed by an image of Somerville based on J. R. Swinton’s chalk drawing of 1848, held in the National Portrait Gallery.

The women represented were vocal about political and social affairs in their lifetimes, and their selection for the window suggests Ogden’s sympathy for the rights of women. Somerville, born in Jedburgh, Scotland, spoke of her disappointment about the lack of educational opportunities for girls.15 At the time, women were discouraged from study as it was seen by many as a manly pursuit, with Somerville stating, ‘From my earliest years my mind revolted against oppression and tyranny, and I resented the injustice of the world in denying all those privileges of education to my sex which were so lavishly bestowed on men.’16 Unhappiness with the lack of opportunity for women is echoed throughout the writings of the other female authors represented. Brontë, Barrett Browning, and Eliot all expressed their frustration at these limitations: a frustration compounded, perhaps, by the need for both Brontë and Eliot to work under male pseudonyms. Jameson and Barrett Browning were also good friends, with the former staying with the latter on occasion when living in Italy.17 Jameson was the author of significant art historical works such as Characteristics of Women (1832), which provided an analysis of Shakespeare’s heroines from the female perspective.

What unites these women is an unconventional approach towards life and a sense of independence. All experienced adversity in their careers because of their gender, yet all were nonetheless prolific in their chosen fields. Political motivations united Barrett Browning, Somerville, and Eliot; Barrett Browning and Somerville were staunchly anti-slavery while Eliot was a freethinking radical who questioned the Christian faith.

Owing to the rarity of a window devoted to women authors at this early date and the careful choices made with every aspect of the portraits, it is tempting to believe that Ogden may have felt an affiliation with these women and their works. How did this relate to his political allegiance? Interestingly, A. N. Scott notes in an address given in 1945 that Ogden received nominations from the Liberals to continue his membership of the town council until 1891, which certainly indicates that there was some respect from the opposing party and may go some way to explain his choices.18 His views were also said to have broadened with the passing of the years and his beliefs that ‘poor folk should have free access to all avenues of intellectual advancement’ led one author to remark that he was a democrat to this extent (‘Local Men of Mark’, p. 6). However, the inclusion of such prominent women also plays into Rochdale’s image of self-help and educational progress across all classes (Joyce, Visions, p. 58). Ogden donated many texts to the collection, so he likely enjoyed the works of these female authors and wished to have exceptional talents of different disciplines on display to inspire the readers who used the space.

Local interest is noted in the Rochdale Observer in 1884 about the inclusion of Brontë, who was described as a ‘vivid describer of our local hill scenery which we feel proud to claim as a native of our immediate district’ (7 June, p. 5). This refers to the proximity of Rochdale in East Lancashire to Haworth, in West Yorkshire, the home of the Brontë family, and the landscape of the intervening South Pennine hills. Lancastrian Rochdale claims the Yorkshire Brontë as its own, an illuminating reflection of the local thought processes involved in the selection of authors.

There was, of course, a long tradition of depicting women in religious contexts in stained glass, yet there are fundamental differences in their depictions. Saints and royalty offered female representation and female donors were also often recognized.19 The development of the memorial window during the nineteenth century also offered husbands and children the opportunity to memorialize their wives and mothers with female saints or virtues.20 However, female representation was still less common, apart from the Blessed Virgin Mary who was often presented in relation to her son. During the Middle Ages, when women are represented, their vitae were often edited and manipulated to emphasize virginity or erudition. In the nineteenth century female figures were also used allegorically in order to embody particular qualities. For example, the memorial window dedicated to Grace Darling at St Aidan’s church, Bamburgh (1855), does not depict Darling herself: her accolades are symbolized by the virtues Charity, Fortitude, and Hope. Darling herself is represented by Fortitude, who replaces the more common virtue, Faith, and she is holding an oar; her image still relies, therefore, on allegory rather than portraiture. The representation of the women authors at Rochdale was therefore distinctive in recognizing their intellectual merit and literary achievements.

Other secular contexts reflecting women and their achievements were slower to take hold. For example, the window inserted at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh, in 1891 depicts an all-male cast: members of the council of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.21 The Carnegie Library at Stockport, built in 1913–15, only contains references to male authors, such as Milton, on the staircase windows. The exceptional subject matter of the window at Rochdale is also in stark contrast to the stained glass at the neo-Gothic John Rylands Library in central Manchester, completed in 1899. The two large windows at either end of the reading room each contain twenty figures, with no representations of women, although the subject matter was largely chosen by a woman. The complex was dedicated by Enriqueta (1843–1908), widow of the entrepreneur and philanthropist John Rylands (1801–1888), but the windows reflect her religious and artistic preferences and, more generally, symbolize the collections of the library. The east window depicts figures relating to literature and art while the west represents those relating to theology. Mrs Rylands selected and placed the figures with advice from Dr Samuel Gosnell Green, the Baptist minister and scholar.22 They were designed by Charles Eamer Kempe (1837–1907), a London-based artist and firm, and use traditional late-medieval compositions consisting of single figures surrounded by architectural motifs. There is a significant distance between the user of the space and the large windows on either side of the main reading room, whereas the windows at Rochdale connect user and space. It is not until 1921 that windows celebrating the achievements of women were inserted at Liverpool Anglican Cathedral.23

At Rochdale the gendered separation of space and the representation in stained glass of that division allowed women authors to be transposed from the domestic into the public sphere; indeed, to take centre stage there in the absence of their male counterparts. The space is defined as feminine. However, while this room functioned as the womens’ reading room during the day, in the evening it became a reading room for boys, revealing the complexity of messages within the usage of one space, but also exposing the young to significant female figures of recent times.24

Other literary men were portrayed in medallions in the upper panels of the windows on the east side of the men’s reading room at Rochdale. These comprised the novelists Scott, Thackeray, and Dickens, the historians Macaulay, Gibbon, and Grote, and, representing periodical literature, Bacon, Addison, and Defoe, echoing the female authors’ window in representing different branches of literature.

Significantly, regional interests are also exemplified in the inclusion of the local authors Edwin Waugh (1817–1890), ‘The Burns of Lancashire’; John Collier (1708–1786), ‘The Lancashire Hogarth’; and the author and banker John Roby (1793–1850). Lord Byron (1788–1824) presided over them in the window above: being Lord of the Manor of Rochdale, he was claimed as a local, notwithstanding his moral notoriety and his disposal of the manor, which had been owned by his family for generations.25 Local pride evidently took precedence over controversy.26

The inclusion of local authors seems to represent an attempt to reconcile tradition with modernity through the use of local dialect. Language connected past and present, which was important for the identity of new boomtowns in the industrial North.27 Collier, known by the pseudonym Tim Bobbin, was a character who did not shy from controversy. He was a caricaturist who produced illustrated satirical poetry in the Lancashire dialect and would travel to Rochdale to sell his work in the local pubs. His most famous texts are A View of the Lancashire Dialect; or, Tummus and Mary (1746) and the illustrated Human Passions Delineated (1773). Collier was also vocal about political ineptitude and attacked the clergy in his texts. These were not safe choices for representation in the library but reveal that local pride and steadfastness of opinion were favoured over societal norms. Collier is buried locally, just a short walk from the library in the churchyard of St Chad’s.

Waugh was born in Rochdale and his most famous Lancashire dialect poem was ‘Come whoam to thi childer an’ me’ (1856). He discussed aspects of Lancashire life in his prose, such as Besom Ben Stories (1865) and Home Life of the Lancashire Factory Folk during the Cotton Famine, 1862 (1867). Significantly, Waugh was present for the opening ceremony of Rochdale Library in 1884 and would have seen his own image in the decorative glass (Taylor, p. 132).

These local men contributed significantly to the ‘canon of Lancashire literature’, and their inclusion in the stained glass reveals that they were as significant to Ogden and the people of Rochdale as Shakespeare or Milton.

Aesthetic style and materials

If portraiture was key to the connection of user and space, so too were colour and light. The composition of the windows is entirely denoted by the leadlines, and the simple use of coloured glass is brought to the fore, revealing a modern approach to design which relies on materials for effect. The expressive use of materials in the windows articulates Aesthetic Movement principles: in the words of one of its pivotal figures, Christopher Dresser, in 1873, ‘A window must fulfil two purposes — it must keep out rain, wind, and cold, and must admit light; having fulfilled these ends, it may be beautiful.’28

The style of the south-facing windows was inspired by a window in Manchester Town Hall, ‘the bordering being the same, but it has been so altered and adapted as to be substantively Mr Ogden’s own design’, referring to the addition of the portraits.29 The emulation of the windows at Manchester Town Hall reflects a spirit both of respect and competition with the nearby city that was characteristic of regional and civic pride in the industrialized North of England.30 Manchester Town Hall achieved national celebrity when it opened in 1877. The windows were made by the London-based glazier Francis Tenant Odell (1820–1881), who produced the glass for Waterhouse’s other major commissions in Manchester, such as the Whitworth Hall and Museum, as well as the rooms adjacent to the tower at Rochdale Town Hall, rebuilt by Waterhouse after fire devastated the original.31

The windows at Rochdale were made by local plumber and glazier, John Tonge, whose premises were on Livery Street, near to the town centre.32 Tonge, it seems, was instructed to make the windows in the likeness of those at Manchester, which he would probably have seen for himself. In the 1881 census, Tonge is recorded as the master plumber, employing three men and one boy: a modest works.33 Plumber-glaziers were not uncommon in earlier periods, and they remained active, but at a booming time for the stained glass industry there was a conscious choice to use local craftsmen.34

The glazing of the windows at Rochdale relies on texture and leadwork for its delineation of form and shape. The windows were largely created from unpainted pale tinted and antique streakie glass, cut into small fragments, creating a mosaic of geometric pattern.35 This represents the interim Aesthetic Movement between the High Victorian and Arts and Crafts styles. Patterns of leaves surround each light in every border, interspersed with clear bullions at regular intervals.36 The lower section of the window is intersected by a delicate design of leaves entirely framed by bullions, which also surround the portraits. Fantastical, imaginary flowers are denoted with leaves sprouting from a central stem. The leadlines of the leaves and foliage become playful and artistic in places, with circular stems twisting around a central bullion. This is a much more modern and contemporary usage of materials, with the glass and lead beginning to be the primary factors in the design and aesthetic.

The colours can be partially reconstructed from news reports which discuss them, as well as the single remaining quatrefoil panel above the original doorway, depicting the Rochdale Borough arms as granted in 1857 (Fig. 5). The colouring of the Rochdale Library windows was predominantly red and several different shades of green, and the designs were specified so as not to occupy so much of the window space as to interfere with the proper lighting of the rooms. The remaining glass in the quatrefoil above the original doorway has a ruby red border and some mid-tone green leaves spread into each foil. The green and red mirror the newspaper reports, but some beautiful glasses are chosen for the mantling, such as antique streakie rubies which gradate through deep orange to red. Although there is some paintwork partly visible on the crest, the shield is almost entirely faded away, with some painted pattern work visible in the glass surrounding the arms. The Rochdale motto, Crede Signo (Believe in the Sign), is still visible in the scroll beneath.

The colours in the windows of the Great Hall at Manchester Town Hall have a soft, subtle tone which is less obvious in the Rochdale quatrefoil. Nevertheless, there are several shades of red in the petals and leaves of the floral motifs, each chosen to harmonize rather than dominate. Rubies and pinks are interspersed with mauves and purples.

To summarize, the hierarchy of glass in the composition had been carefully considered. The backdrop of clear, rectangular quarries naturally allowed the strong geometric pattern and the portraits to stand forward, while not looking overly complex. A sense of space and light was clearly a priority, and the areas not painted or patterned were to be filled with rolled cathedral glass, which would have tempered the glare of the sun’s rays.37 This thoughtful design and use of materials, along with the selection of authors chosen by Ogden, define the modernity of the Rochdale windows.

From narrative to symbolism: the museum and art gallery extension, 1903

The second phase of the building contains stained glass which is much more symbolic in nature and art nouveau in style (Fig. 6). The art gallery and museum was built to the right of the Free Library and presented the town of Rochdale as a centre of high culture (Moore, pp. 262–63). It had been planned since the Free Library was built, as there was a need for a space in which the public could view art (Rochdale Household Almanack, p. 8). The museum was housed on the ground floor and two gallery spaces were placed on the first floor. These additions were much in line with Ogden’s Ruskinian views that art should be available for the advancement of all.38 Ogden, among other local collectors, also contributed to the costs of this extension, which was again designed by Horsfall (Moore, p. 260). Ogden rejected the first set of plans as he believed they were ‘not sufficiently comprehensive for a town of the importance of Rochdale’ and more extensive plans were then created to ‘encourage the appreciation of Art for Art’s Sake’ in order to ‘elevate and refine public tastes’ and provide ‘a source of pleasure and instruction too often neglected in a manufacturing town’.39

This part of the building now contains the main entrance to the gallery and museum and opens out onto a foyer, from which a large stone stairway leads up towards the galleries. At the top the visitor is met by the symbolic art nouveau glass work of Walter John Pearce (1857–1942) (Figs. 7, 8). Several other stained glass firms in Manchester, such as those led by George Wragge (1862–1932) and William Pointer (1866–1919), were also working in this style, linking with other artists and designers such as Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868–1928) in Glasgow, Victor Horta (1861–1947) in Brussels, and Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) in New York.

Pearce was a significant figure in the arts scene in Manchester at the beginning of the twentieth century, producing much secular and ecclesiastical stained glass for the buildings of the North-West of England and beyond. His work reveals changing perceptions and usages of glass in the years between the library and museum phases of the complex. In the library windows there was already a suggestion of reliance on the properties of glass and lead to denote subject and manipulate light, and the glass in the museum and art gallery reflects the full development of this idea, achieving an overall effect of ‘glassiness’.

Pearce was a prominent member of the Northern Art Workers Guild, serving as Master in 1903. His firm was based on Albert Street, Manchester, before moving to Gartside Street and later to Wilmslow.40 As well as designing and making stained glass, Pearce had many other talents. He published a standard text titled Painting and Decorating in 1898, designed several typefaces, patented a glass mosaic process called ‘Vitre-mure’ or ‘Vitremuraine’, and was an accomplished painter as well as an avid photographer.41 He also provided complete decorative glazing schemes for other municipal buildings, such as Bury Museum and Art Gallery, completed in 1901, university buildings such as Sackville Street in Manchester, and the Empire Music Hall in Rochdale (1904). Ecclesiastical commissions included St Aidan’s, Didsbury, now Didsbury Unitarian, where there is a stunning set of windows using symbolic interpretations of flowers as the unifying theme.

At Rochdale there is complete symmetry with the exterior facade of the second phase, part of which is set back from the library (see Fig. 6). All windows on the ground floor contain decorative, floral patterns. Above the doorway, orange flowers are depicted with curving and swirling stems, the leadlines swooping between the panels. Three lights of alternating red and green elongated floral forms are placed either side of the doorway. Directly above, on the first floor, there are two sets of four lights, each with a matching lead matrix. Inside the building, and in the area which is now known as Gallery One, a large, colourful glass dome illuminates the space beneath.42

The windows are representative of Pearce’s art nouveau style.43 The leadwork defines the bulbous and leafy forms at the base of each window. These are connected to the rest of the composition by a central stem, before blooming again at the top. Within this bloom is contained the symbolism or theme of the window. The ironwork of the balustrades on the staircase harmonizes with the elongated leadlines in the decorative glass. On the first floor the windows are connected by wavy, vine-like green glass which flows horizontally across all four panels, seemingly uninterrupted by the mullions. Pearce also utilizes several textured glasses and creatively combines machine and mouth-blown glass to great aesthetic effect.

Representations of ancient science and major contemporary scientific discoveries are present in the two sets of four windows by the staircase. The left set are symbolic representations of the elements of fire, water, air, and earth, whereas, on the right, the exploitation of the elements through science are represented by chemistry, geology, astronomy, and hydroelectricity. This focus on science and the elements reflects the external carved relief stone sculpture by John Jarvis Millson (1850–1919) representing science, art, and literature, which is classical in style and denotes the functions of the building. The inclusion of geology also neatly reflects the museum’s geological collections. There is an eclectic intermingling of styles in the choice of decoration, which combines the Gothic, classical, and art nouveau, showcasing the contemporary taste for combining many design styles within one building.44

The set of windows on the staircase on the left, containing the four elements, prioritize colour and texture over painted decoration and only utilize paint in the depictions of earth and air. This demonstrates careful cutting of the sheets of glass by skilful and knowledgeable glaziers, taking into account the movement and direction of the pattern and the properties of each individual sheet.

In a paper read before the Institute of British Decorators in 1913, Pearce discussed the potential of the varieties of machine-made and mouth-blown glass that were now available:45 ‘We are not driven to the use of small scraps of glass […] but can obtain all the necessary fluctuations in a sky or a pool of water, without destroying its breadth by a network of scaffolding.’ The almost limitless palette available could ‘produce the glow of living palpitating colour’. Pearce believed in truth to materials, stating, ‘Every bit of paint takes from the lustre and prime glory of our material.’46 This attachment to honest and functional design was central to the Arts and Crafts Movement. Texture and colour, along with ‘the indefinable space of atmosphere’, were what was required to produce the effect of the paintbrush.47

In the illustrations of the elements of fire and water, flashed ruby glass is used to embody the licking flames of fire. The effect of undulating, flickering flames, which gradate from white to orange to bright red, is achieved by acid etching producing a simple pattern with a striking effect. Blue is chosen for the background, a colour that links all four images. Varying tones of machine-made blue glass make up the composition of the panel depicting water (see Fig. 7); a carefully chosen piece of glass for the sky progresses from white with flecks of blue towards deeper blue. The texture of the glass also rises and falls with its uneven surface and the glass looks almost like a richly painted canvas of thick oil paint. The sea is a varying mixture of turquoise and darker greens, chosen to achieve a more accurate representation of undulating waves following the leadlines. This expressive use of glass is present in the windows representing the exploitation of the elements. In the image illustrating hydroelectricity, the waterfall is depicted by clear muffled sheet, which again catches the light and sparkles, mimicking the movement of water.48 The different layers of the earth in the panel depicting geology are differentiated by texture as well as colour. This also applies to the rocks in the hydroelectricity image, with the texture moving in a particular direction to accurately represent a rocky plain with indentations visible, which naturally recreate the surface of the hills and rocks.

The minimalistic paint work of the hot-air balloon, signifying air, shows a preference for the glass and lead work primarily to denote subject matter. A rotating earth depicting the continents of Europe and Africa, perhaps reflecting the ‘New Imperialism’ of the late-Victorian and Edwardian periods, is denoted simply with a dark outline and an orange stain for the land. This theme of imperialism is emphasized in the windows on the ground floor, where there is further exploration of the creative qualities of glass. These windows contain symbolic representations of Scotland, England, and Ireland: a thistle for Scotland, a red rose for England and also Lancashire, and a shamrock for Ireland (Fig. 9).49 These floral forms are set against clear rectangular background quarries, as were the windows in the library, and Pearce makes much use of antique seedy glasses, cleverly used to direct the eye and the light.50 Where the light would have shone on the tops of the leaves of the plant, the bubbles of air in the seedy glass catch the light and soften the shade of the green and add natural sparkle.

The flame-like colours of the petals of the red roses in the panel representing England also utilize antique seedy glass which transforms into flames on torches. Thin slivers of green glass weave behind the flowers, rising to hold these torches. The shamrock windows are largely made from varying shades of antique seedy green glass, with some antique streakies being effectively interspersed in-between. Antique seedy and streakie glass is again used for the purple thistles, with a red striation running through a blue, demonstrating the use of select pieces of glass.

Conclusion

The stained glass at Rochdale Library, Museum, and Art Gallery exemplifies the proliferation of its use in secular buildings in towns and cities in the nineteenth century, and reflects how stained glass was commonplace and an integral feature of such buildings. Stained and decorative glass could serve many purposes in a building: it defined physical space while redefining spaces through imagery, and was critical in connecting audiences to buildings, and buildings to their locale. Secular settings widened the popularity of stained glass, yet it is its ubiquity that has often been its downfall in terms of later protection and conservation.

This case study reflects the changes in stained glass design and composition throughout the decades of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with modern materials and concepts being incorporated at each stage. The windows at Rochdale were innovative in thought and design, individual in the representation of the interests of donors, regional in subject matter, and broadcast civic interests and ideals within public spaces. Close study of the windows at Rochdale reveals not only how stained glass interacts with the function and location of municipal buildings, but also how the medium represented and reflected issues of gender, class, and regionalism in the public sphere.

Notes

- Examples of previous studies include those of large firms, including A. C. Sewter, The Stained Glass of William Morris and his Circle, 2 vols (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974–75); and Nicola Gordon Bowe, The Life and Work of Harry Clarke (Blackrock: Irish Academic Press, 1994). A comprehensive overview of Christopher Whall and his circle can be found in Peter Cormack, Arts & Crafts Stained Glass (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015). [^]

- Bill Waters and Alastair Carew-Cox, Damozels & Deities: Edward Burne-Jones, Henry Holiday & Pre-Raphaelite Stained Glass, 1870–1898 (Abbots Morton: Seraphim, 2017); Jasmine Allen, Windows for the World: Nineteenth-Century Stained Glass and the International Exhibitions, 1851–1900 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018). [^]

- There are no existing studies of the architecture and decoration of the building, although a brief description is provided in Clare Hartwell, Matthew Hyde, and Nikolaus Pevsner, Buildings of England: Lancashire: Manchester and the South-East (London: Yale University Press, 2004), p. 597; and Barrie and Wendy Armstrong, The Arts and Crafts Movement in the North West of England (Wetherby: Oblong Creative, 2005), p. 108. [^]

- The use of the word ‘narrative’ denotes figural or portrait windows, as opposed to decorative patterned windows. The portraits in the windows at Rochdale library tell a story and reflect the function of the building. [^]

- Patrick Joyce, Visions of the People: Industrial England and the Question of Class, 1848–1914 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), pp. 57–58, 180–81. [^]

- Rebe P. Taylor, Rochdale Retrospect (Rochdale: Corporation of Rochdale, 1956), p. 132; ‘Our Heritage: Golden key opens door of knowledge on chilly autumn day …’, Rochdale Observer, 21 June 1975, p. 13. [^]

- ‘Local Men of Mark’, Rochdale Monthly, April 1903, p. 6. [^]

- ‘Death of Mr Jas. Ogden’, Rochdale Observer, 6 February 1907, p. 4. [^]

- ‘Death of Mr Jas. Ogden’; ‘Mr Ogden’s Will’, Rochdale Observer, 9 February 1907, p. 7; ‘Local Men of Mark’, p. 6. [^]

- ‘Stained Glass Windows for the New Free Library’, Rochdale Times, 7 June 1884, p. 8. [^]

- ‘Opening of the New Free Library’, Rochdale Observer, 1 November 1884, p. 6. [^]

- Spenser and Chaucer may have been swapped as they do not fit the chronological order of the window. All the portrait window openings have the same dimensions and the Rochdale Times report (1 November 1884) states that Chaucer was in the far-left light when first inserted (p. 8). [^]

- ‘Library Committee Reports’, in Rochdale Corporation: Reports of the Various Committees of the Council on Works Done during the Year Ending March 25 1885 (Rochdale: Haworth, 1885), pp. 18–19. [^]

- Photographs of the window from the early twentieth century show that there were changes in the layout which subdivided the space, so the window may not have been entirely on view to all those who used the library. [^]

- Somerville Hall, now Somerville College, at the University of Oxford was founded in Somerville’s memory in 1879 to promote higher education for women. This predates the opening of Rochdale library by just five years. [^]

- Martha Somerville, Personal Recollections, from Early Life to Old Age, of Mary Somerville (London: Murray, 1874), pp. 45–46. [^]

- Judith Johnston, ‘Jameson [née Murphy], Anna Brownell (1794–1860)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/14631>. [^]

- A. N. Scott, ‘James Ogden and the Rochdale Art Gallery’, Transactions of the Rochdale Literary and Scientific Society, 22 (1945), 72. [^]

- See Christine Hediger, ‘Female Donors of Medieval Stained-Glass Windows’, in Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods, and Expressions, ed. by Elizabeth Carson Pastan and Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz, Reading Medieval Sources, 3 (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp. 239–50. [^]

- For an overview of the development of the memorial window, see Michael Kerney, ‘The Victorian Memorial Window’, Journal of Stained Glass, 31 (2007), 66–93. [^]

- For further discussion of this window, see D. V. Clarke, ‘The National Museums’ Stained-Glass Window’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 120 (1990), 201–24. [^]

- John Hodgson, ‘“Carven stone and blazoned pane”: The Design and Construction of the John Rylands Library’, Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, 89.1 (2012–13), 19–81 (p. 54). [^]

- See Noble Women: Windows in the Lady Chapel (Liverpool: Liverpool Cathedral, 1951). [^]

- Rochdale Household Almanack and Corporation Manual for 1885 (Rochdale: Wrigley, 1885), p. 8. [^]

- ‘Opening of the New Free Library’, Rochdale Observer, 1 November 1884, p. 6; Taylor, p. 81. [^]

- There was some criticism of this choice. It was ‘rather a big stretch, for we are afraid the poetic inspiration did not spring from Rochdale’ (Rochdale Household Almanack, p. 8). [^]

- Patrick Joyce, Democratic Subjects: The Self and the Social in Nineteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), p. 168. [^]

- Christopher Dresser, Principles of Decorative Design (London: Cassell, Petter, & Galpin, 1873; repr. London: Academy Editions, 1973), p. 153. [^]

- ‘Stained Glass Windows for the New Free Library’, Rochdale Times, 7 June 1884, p. 5. [^]

- C. Dellheim, ‘Imagining England: Victorian Views of the North’, Northern History, 22 (1986), 218–23. See also, Asa Briggs, Victorian Cities (London: Penguin, 1990), p. 33. [^]

- Colin Cunningham and Prudence Waterhouse, Alfred Waterhouse 1830–1905: Biography of a Practice (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), p. 233. [^]

- ‘Stained Glass Windows for the New Free Library’, p. 5. [^]

- Rochdale Local Studies Library, Census Records 1881, Registration District: Rochdale, Class: RG11, Piece: 4103, fol. 49, p. 50. I am very grateful to Janet Byrne at Rochdale Local Studies Library for her invaluable assistance with census records and other documentation. By the time of the 1901 census, Tonge was living on Drake Street, Rochdale, a very central and well-to-do location. [^]

- James Moore, High Culture and Tall Chimneys: Art Institutions and Urban Society in Lancashire, 1780–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), p. 270. [^]

- Antique glass is mouth-blown in the form of a cylinder which is then split and flattened. Antique streakie has streaks or striations of a colour, or several colours, running throughout the sheet. [^]

- A bullion, or bullseye, is the raised central ring of crown glass where the pontil iron was attached. [^]

- Rolled cathedral glass is a lightly textured glass in a regular pattern which obscures vision through the glass; ‘Stained Glass Windows for the New Free Library’, p. 5. [^]

- The minutes of the library committee recorded the occupations of those using the service. Throughout the 1880s, factory operatives were among the most frequent users, with many other trades represented. [^]

- Minutes of Proceedings of the Council and the Various Committees for the Month of January, 1902, Library Committee, 30 December 1901, pp. 52–53, Rochdale Local Studies Library; Minutes of Proceedings of the Council and the Various Committees for the Month of March, 1903, Public Libraries, Art Gallery and Museum Committee, 18 March 1903, p. 78, Rochdale Local Studies Library. [^]

- See the product catalogue of the firm, Pearce, Manchester (Manchester: Chorlton & Knowles of Mayfield Press, [1910–15(?)]). [^]

- Discussion with David Pearce, Walter Pearce’s grandson, February 2019. [^]

- A further pair of windows was placed in this room depicting medieval printers’ marks. [^]

- Pearce worked collaboratively with other significant artists in his stained glass designs, such as Lewis Day (1845–1910) and Arthur Lewis Duthie (d.1940), and this could affect the aesthetic. When working with Day, Pearce used slab glass, popular with Arts and Crafts workers in stained glass. Work by Pearce which uses slab glass can be found in St Chrysostom’s, Victoria Park, Manchester, and dates from 1906. [^]

- See J. Mordaunt Crook, The Dilemma of Style: Architectural Ideas from the Picturesque to the Post-Modern (London: Murray, 1987). [^]

- A contemporary account of the variety of glass available for the stained glass industry is contained in Arthur Louis Duthie, Decorative Glass Processes: Cutting, Etching, Staining and Other Traditional Techniques (Corning: Corning Museum of Glass in association with Dover, 1982). [^]

- Walter J. Pearce, ‘Stained Glass, Being a Paper Read before the Institute at the Painters-Stainers’ Hall, London’, Proceedings of the Incorporated Institute of British Decorators, 5 December 1913, p. 15. [^]

- See Cormack, Arts & Crafts Stained Glass. [^]

- Muffled sheet is a machine-made textured glass with a regular uneven surface of medium-depth bumps. It was a very popular glass which could be manipulated and placed in many directions in order to create specific effects. [^]

- Wales was considered a principality and therefore united with England. A mistake was made during a previous restoration of the windows. In the set to the left of the doorway as entered, a shamrock window has been recreated, when this should have been thistles, representing Scotland. [^]

- Antique seedy is a mouth-blown glass with small bubbles or ‘seeds’ of air within the material. [^]