As we work at home, perhaps in a home office but alternatively perched at one end of the dining table or even sitting on the sofa, it is intriguing to think about the fact that the architect John Soane (1753–1837) was a homeworker and that his architectural practice was an integral element of the lived environment of his homes in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

When Soane was a young architect in the early 1780s, just starting out and recently back from his grand tour, he lived in rented rooms and must have worked there, even after he took his first pupil in 1784 — the same year he got married — and his second in 1786. From 1788, when he was appointed as its architect, he had an office at the Bank of England. In 1791 he rented a new office in Great Scotland Yard, presumably using some of the fortune that he inherited from his wife’s wealthy uncle in 1790. He probably chose it because in October 1790 he had been appointed clerk of works to St James’s Palace, the Houses of Parliament, and other public buildings in Westminster, and this location was close to the various government offices.1

However, as soon as he began to build his own house, 12 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, between 1792 and 1794, he immediately began planning to conveniently combine his home life with his expanding architectural practice. To that end, he replaced the existing stables with a hayloft above, at the back of No. 12, with a purpose-designed, two-storey office with a separate entrance onto the mews street, Whetstone Park, behind the house. You can see the skylights of the office behind the serried ranks of potted plants arranged on the roofs (Fig. 1) — gardening in small urban spaces is nothing new!

There are two surviving views of Soane’s office, made in 1808 when it was being emptied as part of the move into No. 13, the rear part of which Soane had just rebuilt.2 One of these views was drawn by Soane’s pupil James Adams on 20 July 1808 (Fig. 2). The walls are hung with plaster casts, most purchased from the collection of the Scottish architect James Playfair, providing a repertoire of ornament for the office to draw upon.

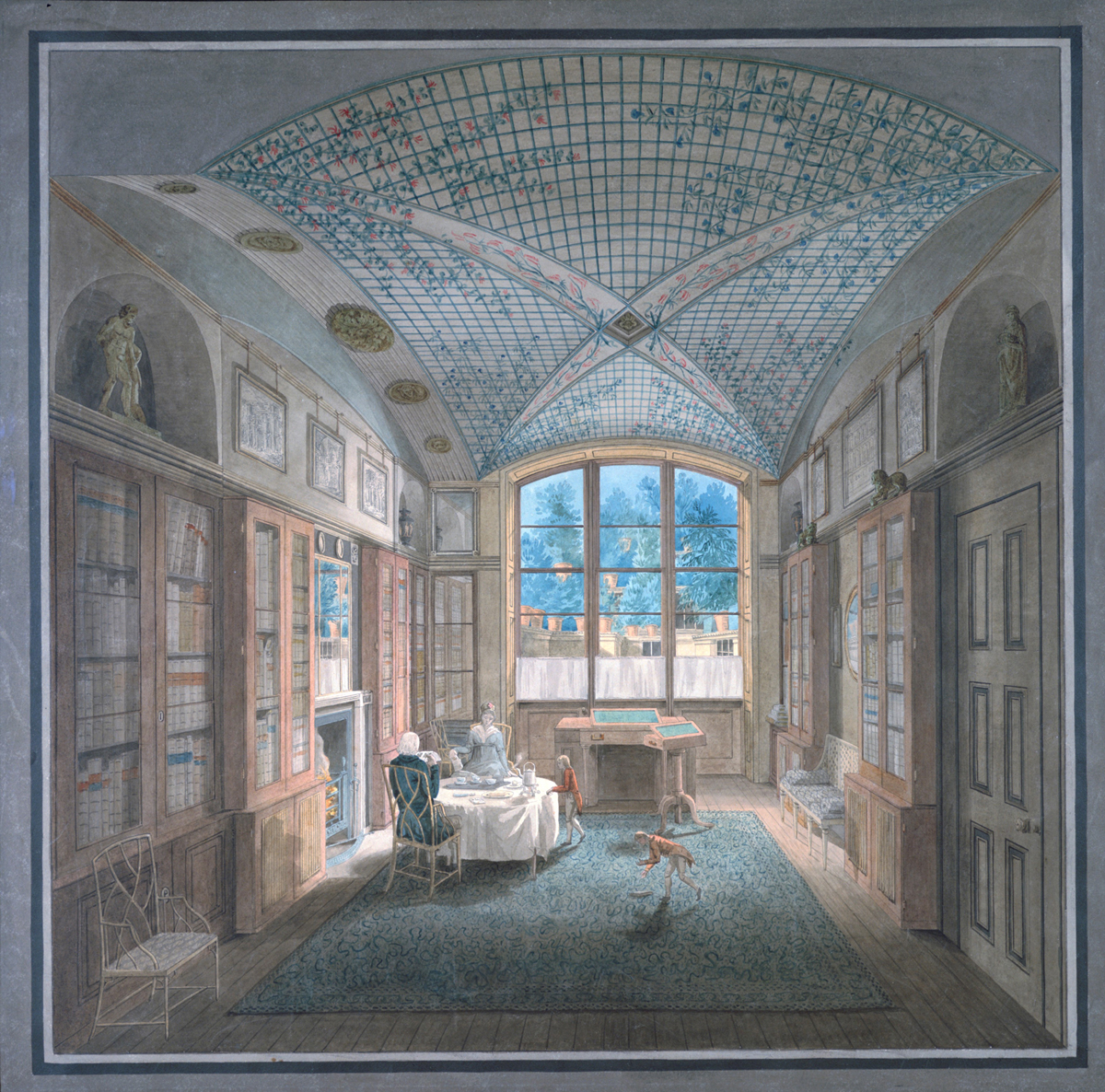

Soane himself probably never worked in this office, however, preferring to use the large desk in his breakfast room (also his library), which appears in Joseph Gandy’s view of 1798 (see Fig. 1). This desk is still in the museum today, serving as a pier table in the library-dining room.3 Soane and his wife Eliza are at the table on the left — he is having breakfast before the day’s work begins or perhaps taking a break for tea with his family.

When Soane redeveloped the rear premises of 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields — the house next door — to extend his home in 1808 and 1809, he constructed new architectural offices with a new external entrance from Whetstone Park. The upper office, as modified by Soane in the 1820s, still survives (Fig. 3). It is tiny and cannot be open to the public. We plan to restore it in 2022–23 and hope to provide some regular access for small groups once that work is completed.

In this office his pupils worked on all the business of a busy practice — copying drawings, writing out bills, working up designs from Soane’s sketches, making site visits, and much else. All this is meticulously recorded in the surviving Office Day Books, which exist in an almost unbroken run for about forty-five years charting everything from individual times of arrival to framing drawings for Royal Academy exhibitions, deliveries of drawing paper, and days off for Jewish and other holidays. The pupils were strictly managed, being absolutely forbidden to go to the kitchens and fraternize with the domestic servants!

The upper office was designed very cleverly with apertures below the desks, infilled with metal grilles (you can see one of these in Fig. 3), which served a dual purpose — they enabled heating pipes to snake through and around, enabling the office to continue to work in winter, but I have always also felt that they enabled the chief clerk, probably seated in the lower office, just below, to hear everything that was said above (Dorey, p. 108). John Soane himself did not ever work in this busy office, and his house was cleverly designed to give him a wide range of options for working at home, each one providing access to a different part of his library of more than seven thousand books.

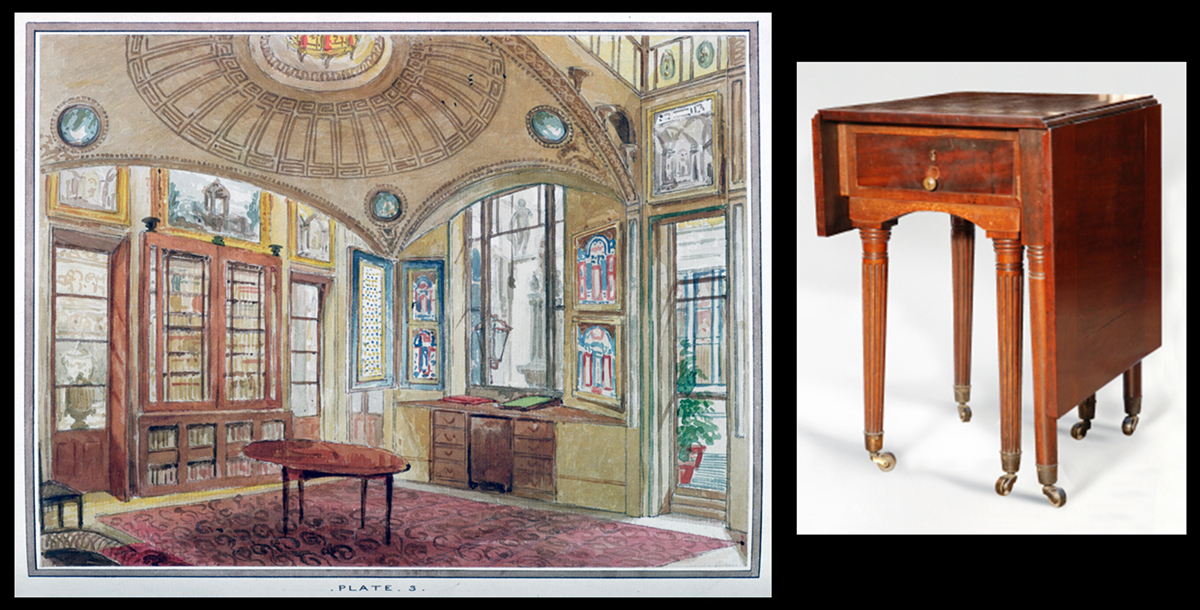

The breakfast room at 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields had a desk built into the window recess with opening cabinets each side for the display of pictures (Fig. 4). Soane described this room as embodying ‘those fanciful effects that constitute the poetry of architecture’ with its coloured glass and more than a hundred mirrors.4 But it was also nonetheless an extremely practical working space — the piece of window glass above the desk, unlike the glass in the skylights and lantern light in the ceiling, was not coloured but clear plate of an unusually large size for the date and casting an excellent light onto the working surface. The space available was used to the full, with ingenious space-saving furniture designed by Soane such as the table — big enough for an architect’s drawing board — that fits neatly into the kneehole of the desk (Fig. 5). It is on castors so that it can be easily moved in and out (Dorey, cats 121, 127).

Turning away from the desk in the window and looking around the room there are other clever designs to optimize the potential workspace function of this room alongside its domestic use. You can just see the edge of the desk in the window recess on the left-hand side (see Fig. 5). Against the wall is a mahogany gate-leg side table — again, unusually for this kind of furniture, on castors (Dorey, cat. 120). This clever piece, designed by Soane, not only has the gate leg to minimize the space it occupies but also incorporates a large portfolio case for big architectural books between its legs. Elsewhere in the room bookcases are cleverly recessed into the walls either side of the fireplace in order to take up the minimum space (Fig. 6).

Even in the heart of the museum, at the back of the house, Soane created an ingenious small space, almost a mini-library, tucked in behind the full-size cast of the Apollo Belvedere that presides over the dome area. Here he could sit, surrounded by bookcases built into niches, and work at the tiny pull-out table recessed into the back of the pedestal of the statue (Fig. 7) (Dorey, cat. 74). The celebrated Picture Room too — where Soane’s Canalettos and two celebrated series of Hogarth paintings, as well as a gallery of architectural perspective of his own projects, were hung — was somewhere he could sit and work. There was another pull-out table on the north side in an aperture (sadly now blocked up) enabling Soane to take out and consult the small volumes stored in the mahogany bookcases, inlaid with ebony, that run round the room below a brass shelf (Dorey, pp. 112–14).

One of Soane’s female acquaintances recalled happy tea drinkings in the mock-Gothic Monk’s Parlour in the basement, below the Picture Room (Fig. 8). But this space too, had another life as a workstation. What looks like a large chest of drawers in the view on the left is in fact an exceptionally deep architectural plan chest, in which Soane kept the more than one thousand drawings prepared by his pupils as illustrations for the lectures he gave as professor of architecture at the Royal Academy from 1806 (Dorey, cat. 101). These large drawings were held up sequentially — the nineteenth-century equivalent of a slide show — as the lectures were delivered. It is intriguing to wonder whether Soane and his great friend J. M. W. Turner sat together in this room discussing their Royal Academy lectures as they were both professors there — Turner being professor of perspective.

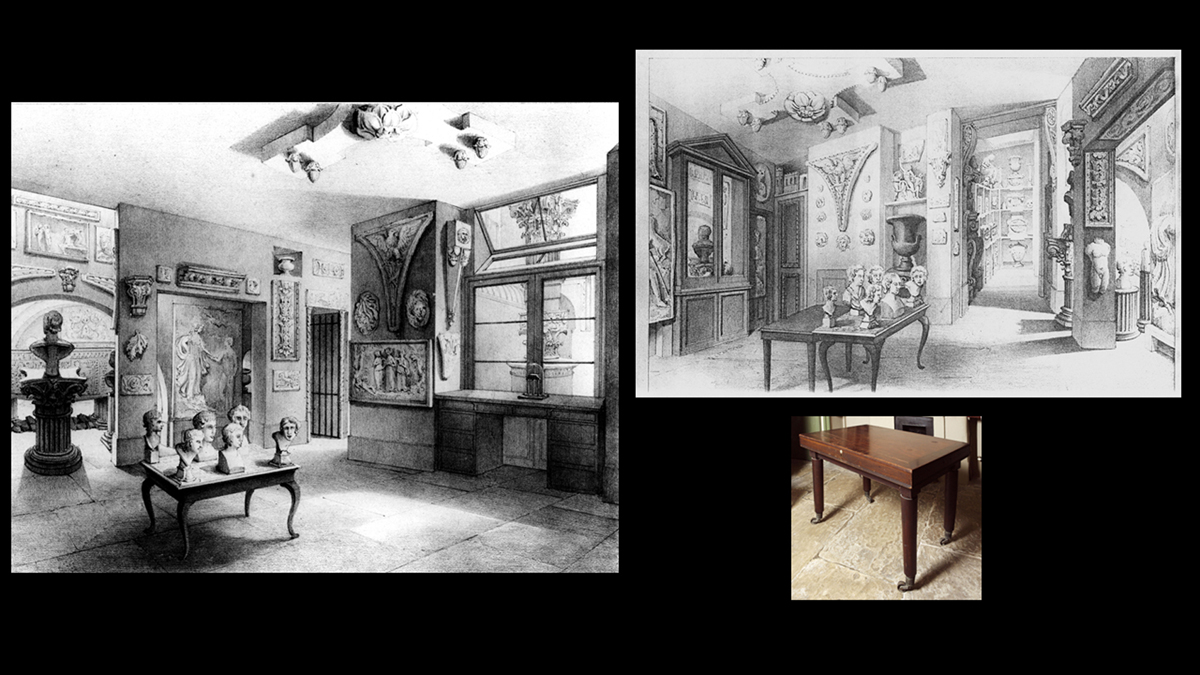

Yet another basement workspace was provided in what Soane called the Ante-Room where there was another very large desk in the window bay (Fig. 9, left) (Dorey, cat. 89). This must have been a late addition to Soane’s arrangements because it blocks a pair of double doors onto the central courtyard. Once again, the workspace is brilliantly designed with excellent light despite its basement location. From the desk the canted window above provided a view of the pasticcio — a thirty-foot column of architectural fragments in the courtyard. This column is a monument to architectural imagination through the ages and its position places architecture right in the centre of Soane’s house, so it is fitting that he had such a good view of it from this desk.

A small model is shown on the desk in the engraving — this was carefully chosen, representing the surviving three Roman columns of what we know today as the Temple of Castor and Pollux in the Roman Forum. Soane had seen and drawn these columns on his own grand tour; he owned numerous casts of parts of this ancient structure and in his Royal Academy lectures he described the temple as the most perfect example of the Corinthian order in the world.5

The engraving (Fig. 9, left) was prepared for a publication on Soane’s house in 1834 but was not published. Instead, another was used, showing an altered arrangement (Fig. 9, right). The table with busts on it has been turned around and another table introduced alongside. This is in fact a wooden portfolio box for drawings, with an ivory disc inscribed with the reference letter M and an internal brass strut support for the lid, which has been roughly screwed to a wooden frame with chunky turned legs and castors to form a table. It is a wonderful example of a somewhat makeshift piece of furniture created to enable Soane to work in this part of the museum — and we know that he kept his drawings for Bank of England branch banks here (Dorey, cat. 90).

Soane’s main personal workspace, his ‘Little Study’, had a desk that he designed himself neatly fitted into the window bay and a pull-out table, once again designed to be the perfect size for a drawing board (Fig. 10). The light that fell onto his work surface was modulated by the use of dwarf Venetian blinds whose angle could be changed by adjusting a turn-screw set into the top edge. It was also softened by the pale-yellow glass in the skylight above, filtering the bright sunshine. He looked out onto the Monument Court with its walls inset with a variety of architectural fragments salvaged from older buildings.

Hung on the walls around him, as we can see from Gandy’s view, was a collection of Roman marble fragments. These had a special personal significance, having belonged to his early teacher, the architect Henry Holland, for whom they had been collected in the 1790s. Soane arranged them himself, using some of the column sections to create the idiosyncratic fireplace surround, flanked by cinerary urns in niches echoing in miniature those of the ancient Roman columbaria where such urns stored the ashes of the dead to form large cemeteries. Just as we sit surrounded by our favourite items and mementos of our travels, so Gandy’s view shows Soane surrounded by his treasures including a fine small group of bronzes on the mantelpiece. On the desk is his inkstand and a quill pen and books are tucked into the specially constructed apertures either side of the desk. A portfolio case with a black cover, full of drawings and paperwork, sits on his table. Two vertical card racks either side of the doorway are brimming with visiting cards, notes, and invitations — as full as our mantelpieces in happier times! (Dorey, cats 64, 65). To the left of the left-hand rack is a little oval picture — a drawing of Soane’s pet dog Fanny, who had died two years earlier, on Christmas Day 1820.6

Figure 10 gives us a glimpse from Soane’s office into the next room, a small dressing room, whose title gives us a hint about how Soane’s working day might have functioned. He could have been called from his study either to meet an important visitor arriving at the front door or to go through the door we see in the distance in the watercolour, which leads into a passageway that goes directly to the office door. Off the narrow passage on one side is a closet where he might have hung jackets or stored his wig and on the other a flushing water closet, a luxury that was matched by a bath and WCs he provided for the use of his servants downstairs in the basement. While Soane washed his hands at the basin in his dressing room or adjusted his cravat in the large mirror hanging on the door, he could have glanced round at a group of framed works that he must have chosen specifically for this private space. These included portraits of two close women friends, Nora Brickenden and Maria Denman, that are the equivalent of our family photographs. They hang near a design for a classical dog kennel in Soane’s own hand — a reminder of happy days exploring the Roman campagna with his early patron, the Earl-Bishop of Derry on his grand tour between 1778 and 1780. A street scene, a copy of one by Canaletto, was a reminder of Venice, and finally, a map of Paris evoked recollections of a city that Soane visited three times (in 1778, 1814, and 1819) whose architecture inspired many of his own (alas unrealized) grand projects for London.

Just as we work at home today in surroundings that we have to a greater or lesser degree personally ‘curated’ to reflect the things that matter to us, so Soane’s ‘Little Study’ and dressing room provided him with an inspirational workspace where he could tackle his projects surrounded with reminders of past pleasures and the world beyond his own four walls.

Notes

- I am grateful to my colleague Sue Palmer, archivist and head of library services at Sir John Soane’s Museum for drawing this connection to my attention. [^]

- In 1806 Soane was appointed professor of architecture at the Royal Academy and as a result decided to consolidate and expand his collections for the benefit of the Academy students. At that time he owned a country house at Ealing, where much of his collection was displayed. In 1807 he bought 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the larger house next door to his own home at No. 12 and began planning an extension across the back. His Ealing house was sold and the collections moved to Lincoln’s Inn Fields. [^]

- Helen Dorey, ‘A Catalogue of the Furniture in Sir John Soane’s Museum’, Journal of the Furniture History Society, 44 (2008), 21–203, 205–48, cat. 38. [^]

- Description of […] the Residence of Sir John Soane (London: [n.pub.], [1835]), p. 54. [^]

- Model SM L70. [^]

- This small oval frame was set into a larger rectangular frame in the 1820s to match a later portrait of Fanny and the pair hung in the breakfast room. [^]