From Balmoral to John Brown, Queen Victoria publicly declared her affection for the Highlands of Scotland, its landscape, and its people throughout her lifetime. The connection was as emotional as it was steadfast.1 The Queen and her Prince Consort made their first visit to Scotland, including the mountainous north-west known as the Highlands, in 1842, reportedly at the request of the Queen herself. They began arrangements to make Balmoral Castle a royal family home as early as 1848, and they soon established an annual residency in the Highlands. It was the first place she visited after the death of Prince Albert in 1861 and her final stay at Balmoral came only three months before her death in January 1901. The royal family’s mode of life at Balmoral was based on a whimsical version of Scotland. This identity is an important signifier of the sovereignty of the British monarchy that is still recognized and celebrated today (Morrison, ‘The whole’, p. 2).

The secluded location of Balmoral Castle provided some degree of royal privacy, but life there became public with the appearance of Queen Victoria’s first Highlands memoir in 1867, a sentimental narrative of royal life dedicated to Prince Albert entitled Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands. The book is a compilation of the Queen’s private journal entries regarding her visits to Scotland in 1842, 1844, and 1847, as well as royal family life at Balmoral from 1848 until the death of Prince Albert. Leaves began its life as a presentation volume for the royal family and friends in 1865, assembled with the assistance of Arthur Helps, clerk of the Privy Council.2 Victoria agreed with Helps’s suggestion that the volume be published for a wider audience. This version included illustrations from sketches by the Queen and Prince Albert, as well as two engraved views of Balmoral Castle.3 It was an immediate success, selling almost twenty thousand copies in its first week of publication.4

In response to the popularity of this edition, the publisher Smith, Elder and Co. released a lavishly illustrated edition in late 1868 to capitalize on the Christmas gift book market.5 In addition to the embossed cover with gilt decoration, this version featured seventy-nine illustrations, including eight steel-plate engravings and two chromolithographs after works by artists under the direct patronage of the Queen. These were interspersed with sixty-nine wood-engraved ‘vignettes’ without a definite background or border, done after photographs or sketches by various artists. The sheer number suggests not only the deluxe nature of the volume but also the importance of the visual image, especially reportage illustration, to the publication. The vignettes fall into three groups: portraits of Highland people, including the Queen’s servants; illustrations of Highland festivities such as the Highland Ball and the Highland Games; and picturesque scenes of the landscape.6

This article will focus on this richly and densely illustrated edition of Leaves, which I consider as ‘illustrated print culture’. In a recent study of popular prints in nineteenth-century France, art historian Patricia Mainardi offered the term ‘illustrated print culture’ as a way to describe the interplay of prints, reproductive engraving after works of art, illustrated books, magazines, and newspapers in the nineteenth century. All of these, she notes, have ‘image value’ — they brought viewing pleasure to the public.7 I borrow the notion of ‘illustrated print culture’ from her for two reasons: first, to signal the ways in which the Christmas edition of Leaves is an example of print culture, filtered not only through booksellers, publishers, and readers, but also through broader discourses around the politics of knowledge, its production, and its consumption.8 In addition, as an art historian, I use the term to recognize the specific modes of printmaking deployed in the volume — from steel-plate engraving to wood engraving after a photograph — in order to draw upon Mainardi’s formulation of image value. To think about Leaves as illustrated print culture would not privilege the images at the expense of the text but would rather consider how the illustrations constitute meaning as images and through their relationship to other images, especially through the commodity form of the Christmas gift book. Such a discussion moves beyond an explanation of illustration (i.e. how the images relate to the text) and towards a consideration of images in dialogue with other images, what W. J. T. Mitchell has called ‘the social field of the visual’.9 What did it mean to look at these illustrations in 1868 as part of a broader Victorian print and visual culture? And what does it mean to do so today? A consideration of the illustrations as ‘illustrated print culture’ foregrounds the visual qualities of the illustrations — from the watercolour sketch to the engraver’s mark — even as it interrogates the politics of representation.

When scholars have turned their attention to the text of Leaves, they have produced rich and sophisticated discussions of gender, monarchy, and celebrity, especially as they relate to the royal domesticity in the Scottish Highlands.10 Victoria was increasingly astute in the ways in which she used the press and publications such as Leaves to shape her public image. She had entered a period of deep mourning upon the death of Prince Albert in December 1861 and all but disappeared from the public eye until the State Opening of Parliament in February 1866. As Margaret Homans has pointed out, the journal reminded readers of her public role while also paying homage to the Prince Consort and an idealized version of the domestic life of the royal family, allying domesticity to sovereignty (pp. 131–46).

For Adrienne Munich, the notion of sovereignty articulated in the journal placed Scottish identity in relation to Great Britain, and a broader articulation of the British Empire, implicit in the text. Leaves was published at a time of emigration, poverty, and renewed nationalistic agitation in Scotland.11 As Peter Womack has noted, ‘the Highlands had the aspect of a residual historical nation — […] the national identity which was both required and eroded by their participation in the imperial adventure.’12 For Munich, therefore, the Scottish venture of Queen Victoria ‘made concrete a kind of British imperial rule based upon a feudal model of patrician activity’ (p. 36). The Highlands became the medium through which to conceptualize Scotland within Great Britain and the British Empire.

Yet these readings have rarely extended to the illustrated version of the text, perhaps because Christmas books such as Leaves present an interpretive challenge, given the dense interaction of text and image as well as the sheer number of illustrations, often executed in diverse media.13 In some cases the lavishly illustrated gift books of the kind marketed at Christmas featured commissions from important artists and represented an original contribution to artistic culture.14 Even as the expansion of media in the nineteenth century upended traditional divisions between high and low, certain forms of cultural production resisted such destabilization and in fact relied upon these categories as a model of communication.15 As I will discuss, the illustrated edition of Leaves required the viewer to distinguish between different types of imagery and different modes of image making, from steel-plate engravings after works of art to quicker and cheaper types of wood engravings like those found in illustrated newspapers.

Although the Queen does not address the illustrations directly in her correspondence, it seems likely that she had a hand in approving the selection for the deluxe edition, especially since she was actively involved in the creation of the first edition.16 John Plunkett has established that Queen Victoria was the ‘first media monarch’, one whose reign kept pace with the vast expansion of the visual image and the advent of new image-making technologies.17 She understood the power of the image, and all the works in the illustrated edition came from her private collection and appeared, according to an advertisement, with her ‘permission’ and ‘sanction’.18 What is at stake here in the conjunction of monarchy, the Scottish Highlands, and illustrated print culture? And what do these have to do with ‘British imperial rule’?

Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose have explored what it meant for the British to be ‘at home with the Empire’, asking ‘was it possible to be “at home” with an empire and with the effects of imperial power or was there something dangerous and damaging about such an entanglement?’.19 In order to address these questions, I will examine two different types of illustration that appeared in Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands: steel-plate engravings after watercolours by the Bavarian artist Carl Haag and engravings after watercolour sketches of Highland Games by the Swedish artist Egron Lundgren. At first glance the separation of these illustrations both temporally and in the space of the text may make them appear as disparate, unrelated illustrations by different hands. In the course of this article, I will argue that both worked to construct the Highlands as a site of familiarity within the bounds of the nation, while simultaneously signalling its otherness and proximity to the more far-flung reaches of empire. Rebecca Steinitz has described the feeling of loss that permeates the text of the journal through the leitmotif of travel, acknowledging that domesticity appears ‘primarily in the context of its loss, that is, as a site of desire impossible to realize, a place travelled towards but never fully reached’ (p. 146). The notion that domestic life at Balmoral was a perpetual voyage to an unreachable — or unknowable — destination provides a new perspective on the Queen’s decision to repurpose works by Haag and Lundgren, both foreigners who found fame as itinerant artists, as illustrations. While the text speaks of loss, the illustrations assert the central role of the male Highlander in constructing the continued dynamic of royal family life, sovereignty, and empire. As a result, the illustrated edition of Leaves is about domesticity and empire, even as it eschews direct references to current events of the period that directly threatened both.

Carl Haag at Balmoral

Carl Haag emerges as the artist responsible for shaping the image of the royal family in the journal. This choice might seem surprising given the long-standing relationship between the Queen and Sir Edwin Landseer, an artist renowned for his Scottish subjects.20 Yet Landseer appears only once in the Christmas edition of Leaves, while Haag becomes the artist responsible for illustrating the rhythms of royal family life in the Highlands. It may be that the Queen and Prince Consort felt a sense of kinship with the artist, who came highly recommended by Prince Karl III of Leiningen (the Queen’s half-brother) and Duke Ernst II of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the elder brother of Prince Albert.21

Haag seemed eager to pursue royal patronage, augmenting the already robust Anglo-German cultural mix of the royal court. He joined them at Balmoral in September and October 1853. As a dedicated hiker himself, Haag was ideally suited to cast the outdoor pursuits of Albert in a distinctly masculine light and allow him to take his place as the head of the household while at Balmoral. Nevertheless, Haag approached royal life with the eye of an itinerant artist, having spent much of the preceding decade travelling through Italy, Germany, and Switzerland. He stands apart from the culture through which he travels, and this approach suffuses his views of life at Balmoral.

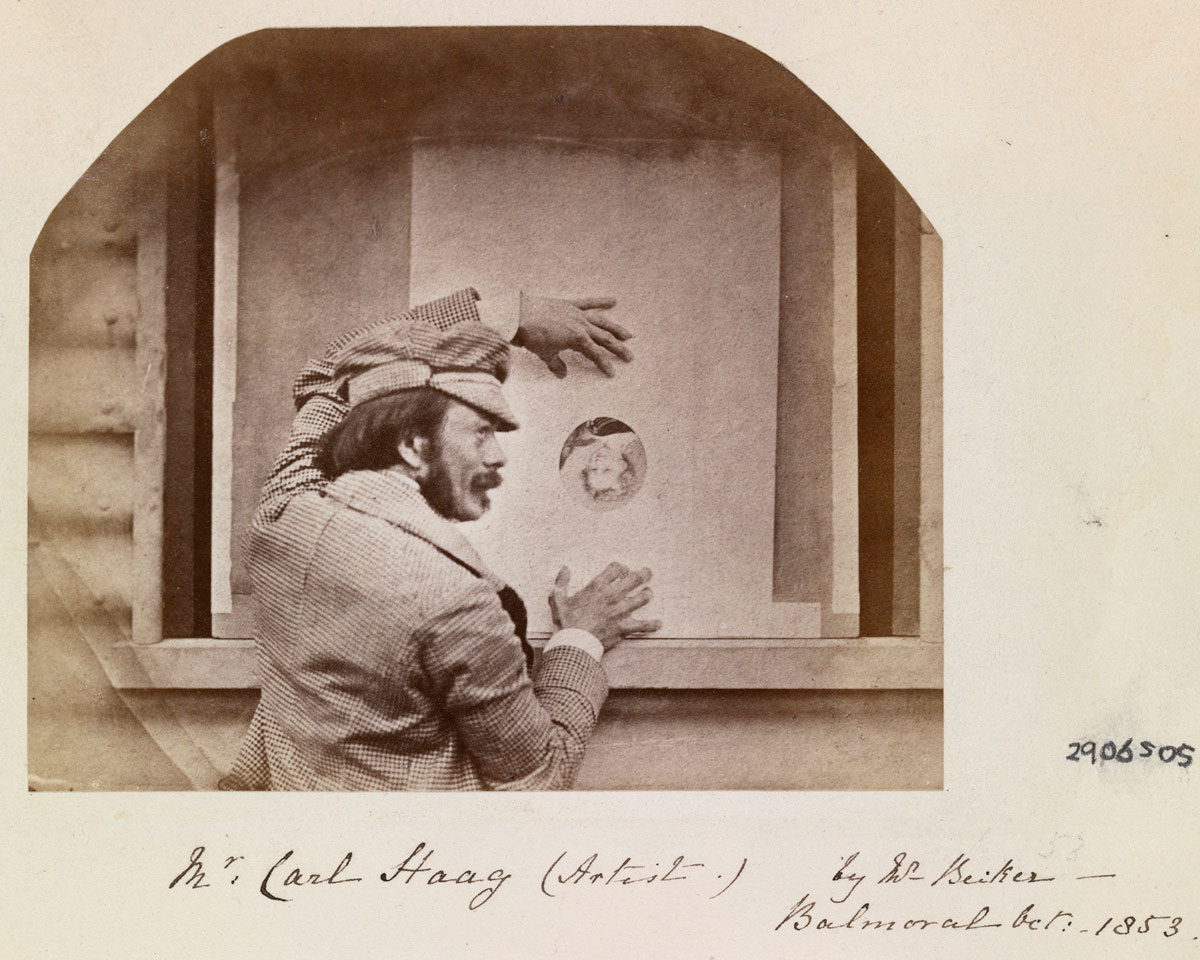

Haag seemed keenly aware of who was, and who was not, worth picturing. Dr Ernst Becker, Albert’s private librarian who was also an accomplished and prolific amateur photographer, assisted Haag by creating photographs.22 In October 1853 Haag turned this lens upon himself, posing for a humorous profile portrait outside the Iron Ballroom, a corrugated iron structure relocated to Balmoral from the Great Exhibition, which served as his makeshift studio (Fig. 1). A smile plays underneath his prodigious moustache as he places his hands on a board balanced on the window ledge. It is only upon closer examination that the subject of this photograph comes into focus. Haag secures a board in the window onto which is affixed, upside down, another photograph: a detail of Franz Xaver Winterhalter’s portrait of Prince Arthur playing with a doll from 1852. Haag would leave Balmoral on 22 October and he gathered the sketches and photographs he would need to finish his royal commissions from a distance. He required an image of the young prince and enlisted Becker’s help to photograph Winterhalter’s portrait. Becker reveals a few tricks of the trade: taking a photograph of a photograph (rather than the original painting) would overcome the limited depth of field achieved by cameras in the 1850s and thus allow Becker to amplify the head of Prince Arthur in the era before enlargers.23 By placing the photograph upside down, Becker ensures that it will be oriented correctly in the ground glass viewer of his camera, helping him obtain an image in crisp focus. The photograph upends the traditional dynamic between artist and sitter and provides a humorous commentary on the tribulations of the modern court painter. The royal subject appears as an image, and a topsy-turvy one at that, while the artist becomes the subject of the portrait. This photograph of the artist as studio assistant suggests the elisions and substitutions engendered by royal patronage and royal life in the Highlands.

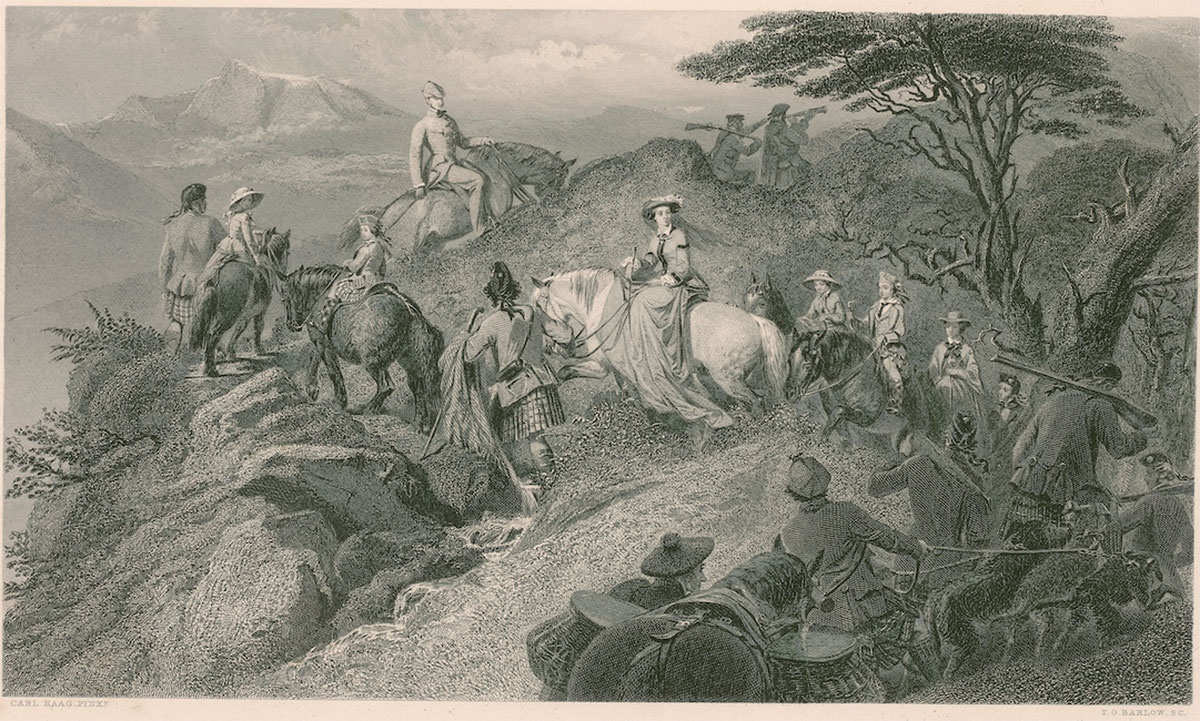

During his time at Balmoral, Haag received a commission for two large watercolours presented by the Queen and Prince Albert to each other: Morning in the Highlands: The Royal Family Ascending Lochnagar was Prince Albert’s gift to the Queen for Christmas in 1853 (Fig. 2). Its pendant Evening at Balmoral Castle was a birthday present from Victoria to Albert in August 1854 (Fig. 3).24 The royal couple often presented each other with works of art as gifts and keepsakes, but these paintings also had a public function, exhibited at the Old Water Colour Society exhibition in 1854 before travelling to the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855 and then the Art Treasures exhibition in Manchester in 1857. They were public declarations of affection and domesticity by the royal family and showpieces for the artist, demonstrating his attention to local topography and numerous portraits of family, courtiers, and servants. In preparation Haag attended the showing of the stags on 10 September 1853 and witnessed the royal party send-off on the ascent of Lochnagar, a mountain peak in the Grampians, on 17 September. I will focus my analysis on Morning as it became the centre of Haag’s residency at Balmoral, and it occupies a privileged position in the volume, situated immediately after the Queen first introduces Balmoral. In tandem with its pendant Evening, Morning suggests the challenges of depicting royal life in the Highlands, even as the composition uses the Highlander to negotiate an energetically masculine identity for Prince Albert.

A day in the life: Morning in the Highlands and Evening at Balmoral

Morning established the rhythm of an ideal day in the Highlands, structured around hunting and family life. Haag uses a sinuous ‘S’ curve for the composition, as the royal party traces a switchback in the mountains. While Prince Albert follows closely behind two Highland guides to lead the ascent, the Queen occupies the centre of the composition, in the midst of her children and servants. A complicated network of gazes unites the various members of the royal party: John Grant, the head keeper at Balmoral, raises his left arm to indicate a forward path, while a gillie (a local term for a hunting or fishing attendant) next to him raises a telescope as if to check the way. Grant’s rifle both echoes the gesture of his arm forwards and reaches backwards over his shoulder, connecting him to Albert.

The figure of the Prince Consort acts as a fulcrum that tilts between the two diagonal lines ordering the composition: the line of his horse and his cane create one diagonal, leading the eye from John Grant through the curves of the landscape and the royal party; his body and the reins of his horse follow a different axis, guiding the eyes of the viewer to the Queen. While Albert trains his gaze on Victoria, she looks back over her shoulder past the royal party and off into the distance, seemingly enraptured by the landscape. Her crop and the folds of her dress continue to guide the eye down the diagonal to the muzzle of a rifle and the dog leashes below. The composition suggests that even with the Queen at its centre, it is Albert who animates life at Balmoral. Evening pursues this complex power dynamic to its conclusion: the presentation of a magnificent dead stag to the Queen and guests as she pauses on the threshold of Balmoral.

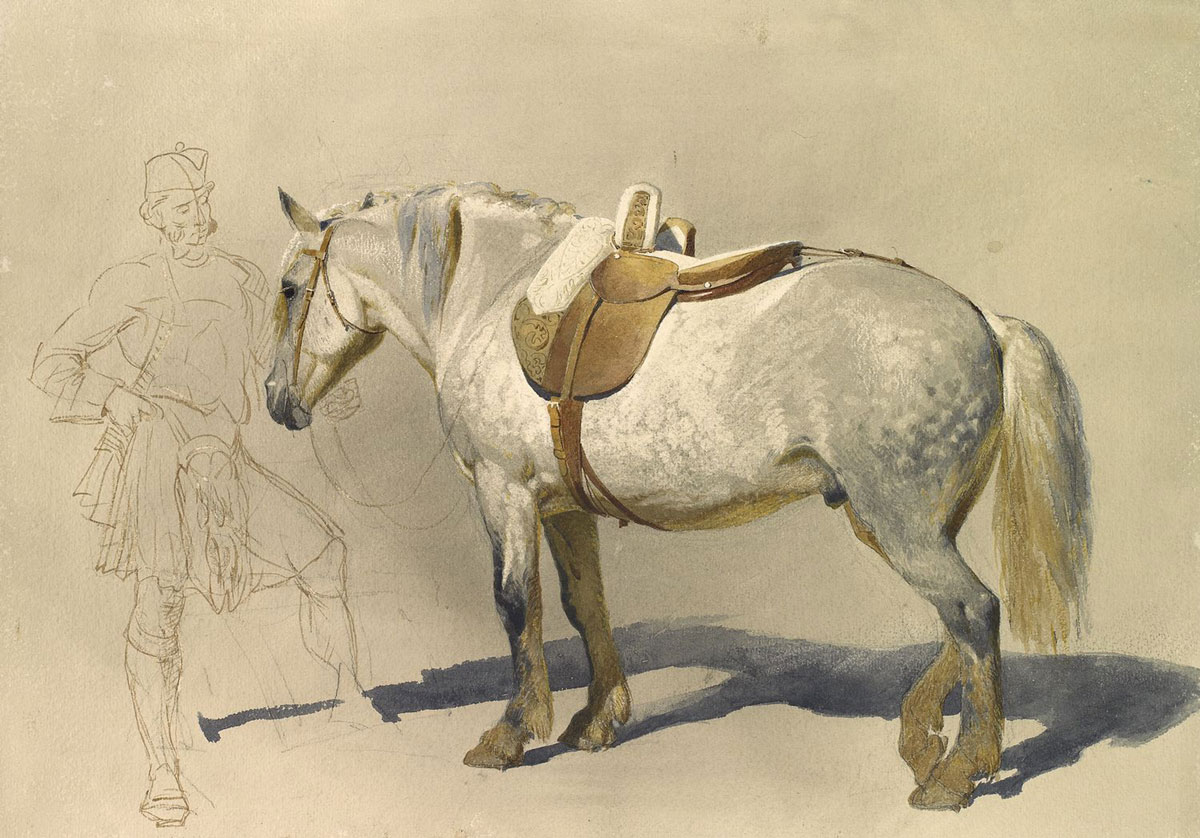

Queen Victoria desired that Haag ‘should see all’ in the creation of these works (Millar, Victorian Watercolours, I, 388). The numerous studies produced for this painting and its pendant, alongside the photographs by Becker, suggest that Haag took great care with the pose and expression of each figure, including the animals. A watercolour drawing of the Queen’s pony pays loving attention to the long eyelashes that fringe his mournful eyes while short strokes of body colour convey the sheen of his belly (Fig. 4). Tellingly, what does not appear in detail in this study is the groom. Sketched quickly in sepia, his only role is to anchor the animal for Haag’s gaze. While the final watercolour lavishes attention on the portraits of the royal family and a few trusted retainers, most of the Highland servants appear in profile or from behind.

With Evening, the marginal figure of the male Highlander is central to Albert’s own royal masculinity. Maureen Martin has discussed the way in which Scotland presented a ‘primal masculinity’ in the English imagination, one allied to the stag and the hunt through the figure of the ‘brawny kilted Highlander’.25 The Queen’s favourite John Brown serves as a kind of Rückenfigur, a figure in the foreground seen from behind who functions as a proxy for viewers, inviting them into the scene. Use of such figures was a popular convention in German Romantic painting that would have been familiar to the artist. Yet Brown is also a pendant to Prince Albert. The Queen expressed an interest in the people of the Highlands, a mixture of admiration and curiosity defined in ethnographic terms. She paid special attention to Brown. He has ‘the independence and elevated feelings [that is] peculiar to the Highland race’.26 In fact, after the death of the Prince Consort, Brown became her most constant companion until his own death in 1883. He receives the longest biography in her journal, described as ‘singularly straightforward, simple-minded, kind-hearted, and disinterested’.27 The second volume of Leaves, published in 1883 and entitled More Leaves from the Journal of a Life in the Highlands, is dedicated to him.

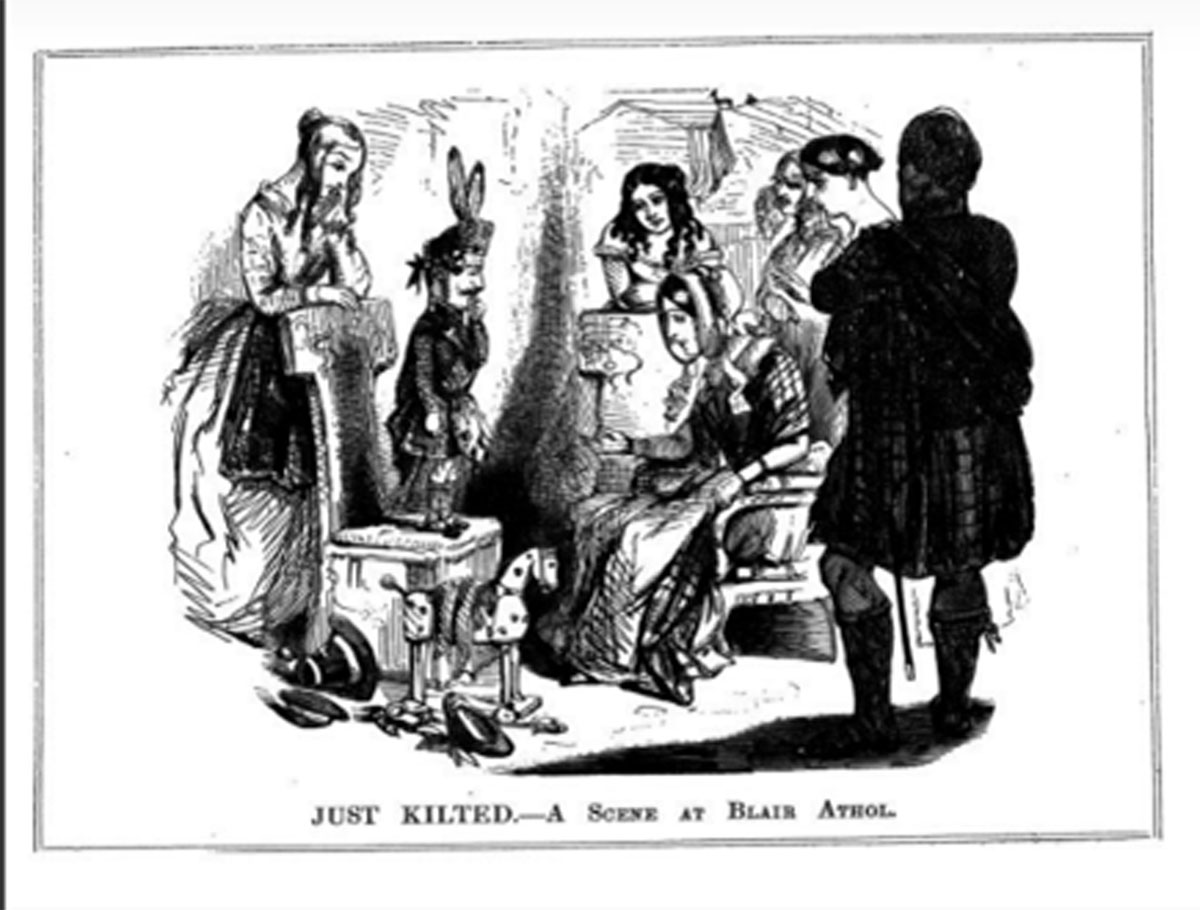

In Evening the pairing with Brown bolsters the masculinity of the prince. Satirists and cartoonists had seized upon the perception of Albert as an effete foreigner in thrall to a powerful woman in public as well as in private.28 Even the manly physicality of outdoor pursuits in the Highlands was not enough to protect him from jabs such as John Leech’s ‘Just Kilted. — A Scene at Blair Athol’ published in Punch in 1844, even though Albert did not wear a kilt until 1847 (Fig. 5). A pint-sized version of the prince stands on a chair in a nursery and shows off his new Highland ensemble to the Queen and her ladies, whose expressions range from amusement to pity. According to Adrienne Munich, this royal adoption of native costume ‘constructed nationalistic mythologies, with the couple performing a selective royal genealogy as a way of declaring their sovereignty over the “races” of Britain’ (p. 24). In the cartoon, however, Albert is a child dressing up in the ominous shadow of a real Highlander, a figure seen from behind who crosses his arms in frustration and possibly indignation at the spectacle of the puny prince appropriating his native dress.29

The painting counters this comical dynamic by showing Brown and the prince as the same height even though Albert is farther in the background and, together, they provide the front and back of a complete kilted figure. Brown remains on the margins, grouped with the other servants, while Albert firmly grasps the antlers and sports the Royal Stewart tartan and the Order of the Thistle. This particular stag was a prize kill for Albert as the largest he ever shot. The proximity of Brown and the other servants to the animals of the hunt indicates their virility while also placing them in the service of the English monarch.

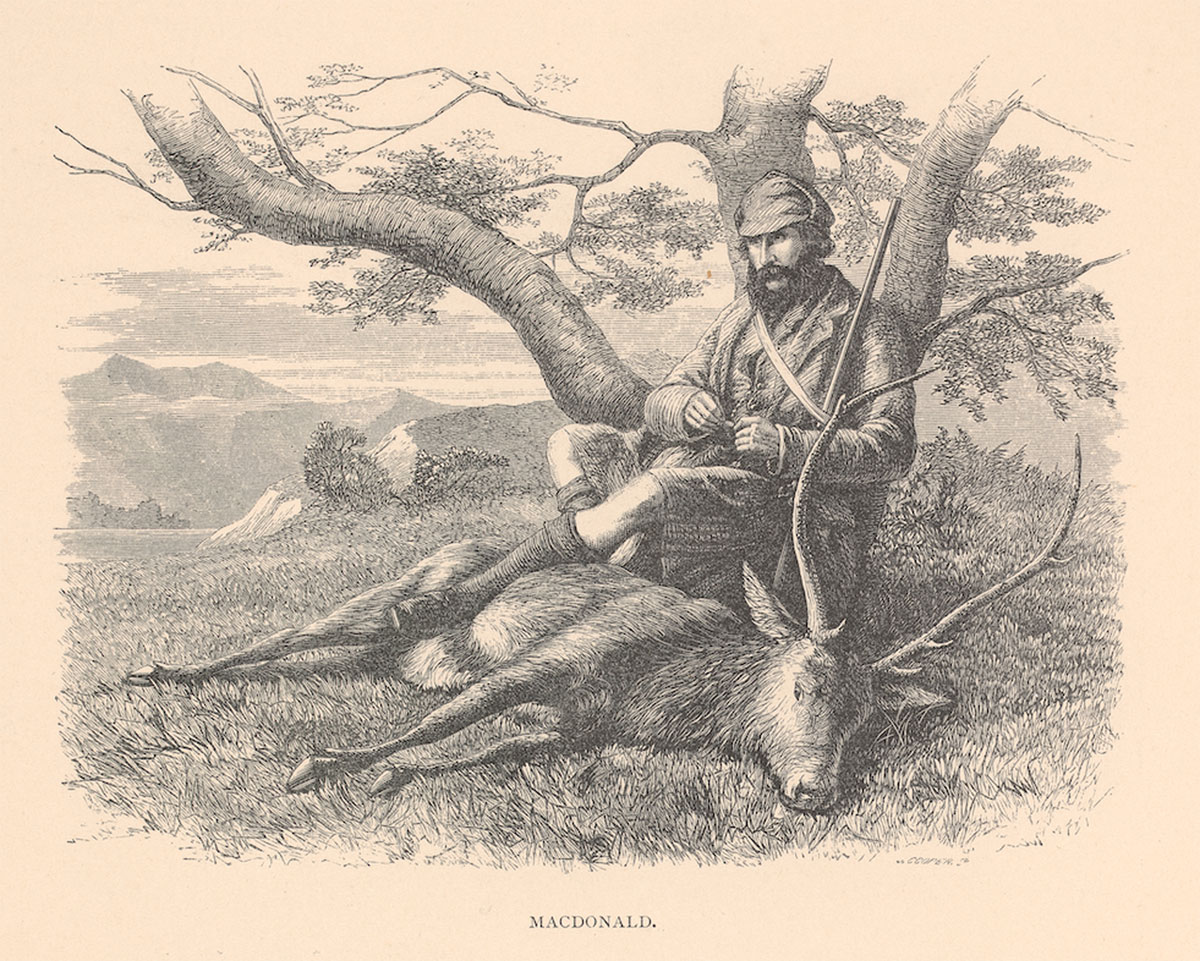

This function of the Highland servant as a prop for Albert’s manliness emerges not only in Evening but also in other illustrations in the journal, specifically in the portraits of Highland servants. ‘J. Macdonald, the Prince Consort’s Jäger, with a stag’ is the first such image presented to the reader (Fig. 6), based on a photographic portrait by Wilson and Hay of James Macdonald with a stag shot by Prince Albert on 6 October 1854 (Fig. 7).30 The title Jäger, German for ‘hunter’, was used by the Queen and Prince Consort for outdoor servants, but in this instance it is specific, indicating Macdonald’s important role in the hunt. Macdonald would lie in wait, telling the Prince Consort when and where to shoot. The photograph suggests that the engraving is a straightforward copy. Both images show Macdonald in the Balmoral plaid kilt and tweed jacket required of keepers and gillies, nestled among three large tree branches.

A closer look, however, reveals that the engraver James Davis Cooper provided a more dramatic backdrop by replacing the picket fence on the grounds of Balmoral with a Highland glen and mountainous crag. Other changes more firmly ally the servant with the stag. The gun, a prominent object in the photograph that creates a diagonal line uniting Macdonald and the stag, is moved aside in the engraving, and the affinity between Jäger and stag is emphasized by the way in which Macdonald firmly plants his left foot in the animal’s groin. Macdonald and, by extension, Prince Albert both claim the vitality of the stag and demonstrate their mastery over it. This union of domesticity and sovereignty had a specific resonance for the Queen and the Prince Consort since he was an anomalous figure in the history of the English monarchy as the Queen’s husband. Together with Morning and Evening, these engravings counter the sting of popular satirical images.

Medium and message

Within the pages of the journal, wood engravings after photographic portraits of servants worked with the steel-plate engravings after Haag’s watercolours to create a unified picture of royal sovereignty and domesticity. Yet the visual register of the steel-plate engravings remained distinct. While the other illustrations would be set with the metal type used for the text, steel engravings were printed separately, on better quality paper, and bound into the printed volume. By the 1860s steel engravings conjoined two competing desires: reproducibility and authenticity. As a harder metal, steel plates, which first appeared in 1822, promised a larger print run. One key aspect of the expansion of print media in the early nineteenth century was the notion that it would popularize art by broadening the viewing audience in part through wider distribution.31 As such, steel engravings were a privileged form of illustrations: listed first, they advertised the luxury and artistry of the volume.

Thomas Oldham Barlow, an engraver known for skill in replicating popular works of art who taught etching at the South Kensington Schools of Design, executed Morning (Fig. 8), while Lumb Stocks produced Evening (Fig. 9). The hardness of steel required considerable strength to engrave and most ‘steel engravings’ used as book illustrations are actually a combination of etching and engraving.32 For this reason the engravings restore some of the patchwork quality to these images. While the watercolour was assembled from various studies and photographs, the engraving takes shape through the layering of marks.

Like many engravers, Barlow economizes where he can. The upper reaches of the sky, for example, were created by guiding a burin along a straightedge, while the Queen’s dress and the jackets of the servants reveal the same technique, with sets of straight lines angled to create a dense cross-hatch pattern. Other areas could have been created only through etching, such as the crags and foliage in the foreground of Morning comprised of lively, short strokes. At the same time the monochrome gives renewed prominence to Queen Victoria as a point of illumination. The white pony in Morning and the white gown in Evening further emphasize her central role in each composition. The replication of these watercolours as steel-plate engravings enhanced the aura of fine art that they gave to the deluxe edition, yet in the pages of Leaves they take on an unintentional, if confused, specificity. The illustrations fall within an account of 1848, five years before the events depicted. The painting oscillates between the general and the particular, suggesting a royal ritual — it is only ‘morning’ or ‘evening’ rather than a specific day or event. In contrast the engravings function as illustrations, assuming a specificity in relation to the text that they did not necessarily have in real life.

Haag was a seasoned traveller and after he left Balmoral in 1853 he spent the remainder of the decade travelling through Egypt, Palestine, and Syria.33 At times his orientalist paintings revisit themes he encountered at Balmoral, such as the complex relationships between servants and potentates, the struggle against nature, and the dynamic between humans and animals, even as his relationship with the royal family deepened. He visited Prince Alfred in Cairo in 1858, where he was serving in the navy, and a number of his orientalist works entered into the Royal Collection (Karbach, p. 187). As Frederick Wedmore noted in the Magazine of Art, Haag moved beyond typical orientalist subjects, such as harem scenes, to treat domestic life, as in the loving Bedouin family of Happiness in the Desert from 1867. More than that, what connects Haag’s orientalist works, and the idea of orientalism in general, to his paintings for the Queen is the tension between the specific and the general; his reputation is based upon first-hand observation, and yet there is the expectation that individuals stand in for types.34 He later received a royal commission for two further works that commemorated royal life in the Highlands in 1861, during what would be Prince Albert’s final visit to Balmoral: The Queen and the Prince Fording the Poll Tarf (1865) and Luncheon at Cairn Lochan, 16 October 1861 (1865). Both appear as steel engravings in Leaves.

At Balmoral and beyond Haag demonstrated his skill in domesticating the unknowable aspects of foreign cultures. Victoria was a spirited participant in the ‘Celtification’ of Scotland, the name given to the cultural formation of a Highland identity in the British popular imagination in the first part of the nineteenth century. As Charles Withers has written, ‘the Highlands are both real — an area of upland geologically largely distinct from the rest of Scotland — and they are a myth, a set of ideologically laden signs and images.’35 Since the Act of Union in 1707, the Highlands region of Scotland rested uneasily within Great Britain.36 As the fear of Jacobite revolt subsided, the service of Highland regiments in the British army completed the transformation of the Highlander as defender of Great Britain and staunch supporter of the British Empire.37 Part of this process involved the dislocation of traditional Highland identity and its subsequent incorporation into a larger conception of ‘Britishness’. As Murray Pittock notes, ‘it was safe to see Scotland in terms of a culture which hardly existed any longer, and was, in any case, in no condition to resist.’38 As Haag’s watercolours indicate, Highland identity structured the very nature of royal family life at Balmoral, whether morning or evening.

The situation in the Highlands revealed the paradox of colonizer and colonized, especially in relation to an internal colony. Although Haag depicts the Highland servants in a way that bolsters the masculinity and sovereignty of Prince Albert, the use of his paintings as illustrations calls to mind John Barrell’s formulation of ‘this/that/the other’ in his study of Thomas De Quincey and imperialism. As he states,

there is this here, and it is different from that there, but the difference between them, though in its own way important, is as nothing compared with […] that third thing, way over there, which is truly other to them both.39

In this formulation the Highlander would be ‘that there’ which can be made over and integrated with ‘this’, the British monarchy. The people of India, for example, whose strike at independence in 1857 was put down by Highland regiments, as I will discuss, are ‘other’ to them both. According to this logic, the Highlanders, colonized by the English at home, became colonizers for the British abroad.

It seems particularly appropriate that this process of othering, what Barrell terms a ‘psychopathology’, happens in and around the royal family home of Balmoral in the Queen’s Leaves. Sigmund Freud used the German term unheimlich to describe the unsettling nature of the intermingling of the strange and the familiar, linking the term to its etymology. Heimlich in German means ‘secretive’ but, as Freud notes, its root contains the idea of the heim or home — ‘intimate, friendly, comfortable’.40 Haag’s watercolours, publicly exhibited and then reproduced within the journal, made public the secret home life of the royal family. At the same time they rely upon a kind of colonial uncanny, situating life in the Highlands as comfortably familiar and yet still other. Mary Louise Pratt viewed this type of description as a familiar aspect of ‘othering’: ‘The people to be othered are homogenized into a collective “they”, which is distilled even further into an iconic “he”.’41 Queen Victoria does not disguise her frank admiration of Highland masculinity in Leaves. She finds Macdonald the Jäger to be ‘tall and handsome’, and she likewise praises John Brown as the ‘strongest and handiest’ of her servants (pp. 65, 113). The ideal of domesticity at Balmoral, as depicted by Haag, relied upon the iconic ‘he’ of the Highland servant as well as his differentiation from the Queen and her family.

In the Christmas edition of Leaves, the figure of the male Highlander comes to the fore through the illustrations after sketches by Egron Lundgren. After Haag departed in 1853, the Queen did not extend another invitation to an artist to visit Balmoral until Lundgren arrived in September 1859, almost directly from India, where he had spent nearly a year at the request of the Queen (Karbach, p. 99). He records in his memoirs that she sent him on a ‘mission’ to record the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and that he planned to contribute to an illustrated volume planned by Thomas Agnew & Sons.42

Yet, to judge by the pages of Leaves, such momentous events did not intrude on royal life in the Highlands. While the volume contains detailed news of the fall of Sebastopol, a crucial British victory during the Crimean War, the Indian Rebellion and its aftermath do not appear in the published text. Yet the royal party witnessed a Highland regiment parading in Portsmouth before departing for India as they travelled from Osborne House to Balmoral in August 1857 and the Queen does comment upon and records details of events in India in her journal in September 1857.43 Despite the rebellion’s apparent omission from the volume, we know that the Queen played a crucial role in facilitating Lundgren’s work in India, and she visited his exhibition at Agnew & Sons upon his return.44 Lundgren’s sketches from Balmoral communicate in the vernacular of reportage rather than fine art and, as a result, his works do not treat the royal family as subjects. Instead, his illustrations in the journal take their place alongside a proliferating and popular visual catalogue of the ‘peoples’ of the British Empire.

The Swedish sketch artist at the Highland Games

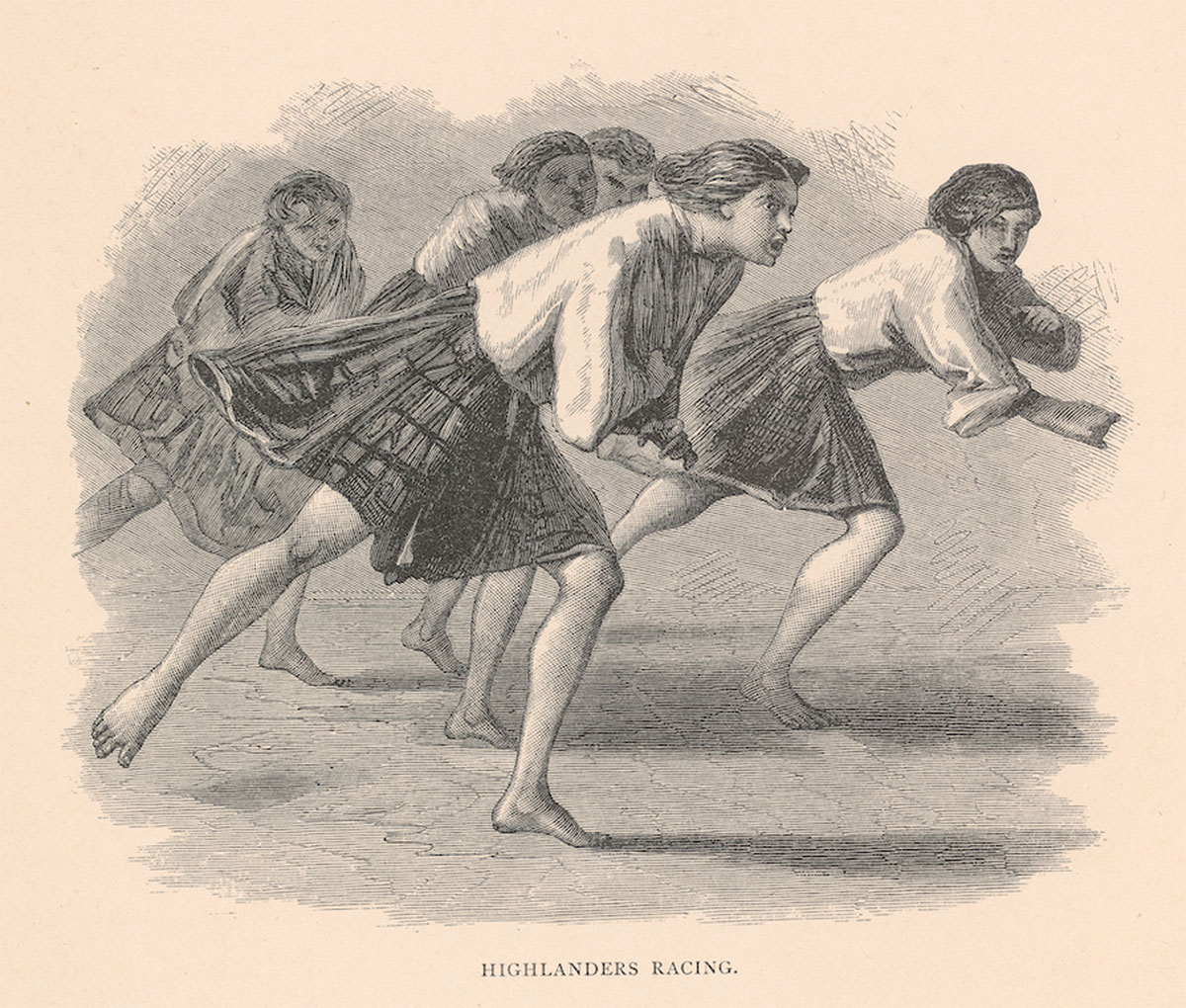

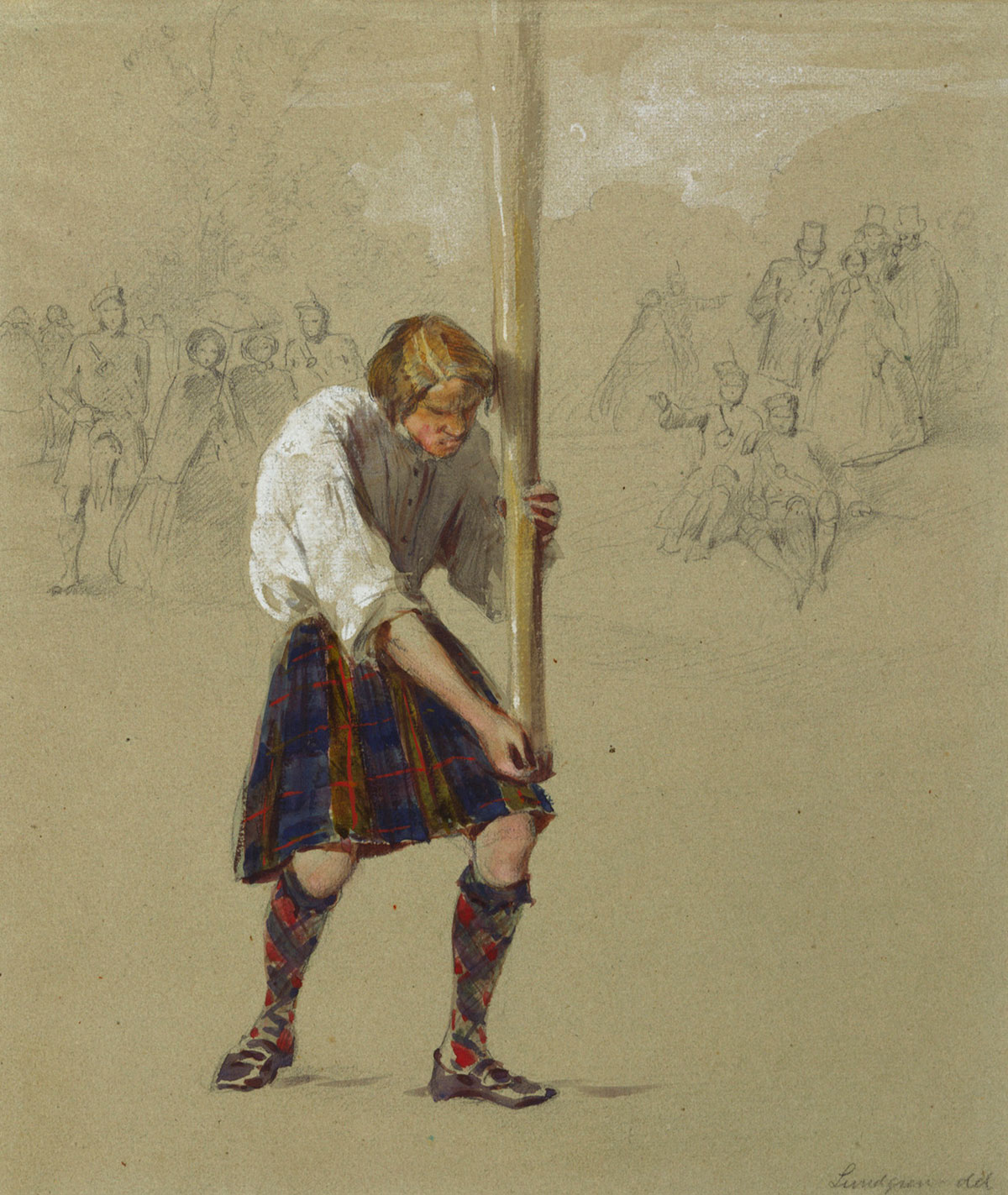

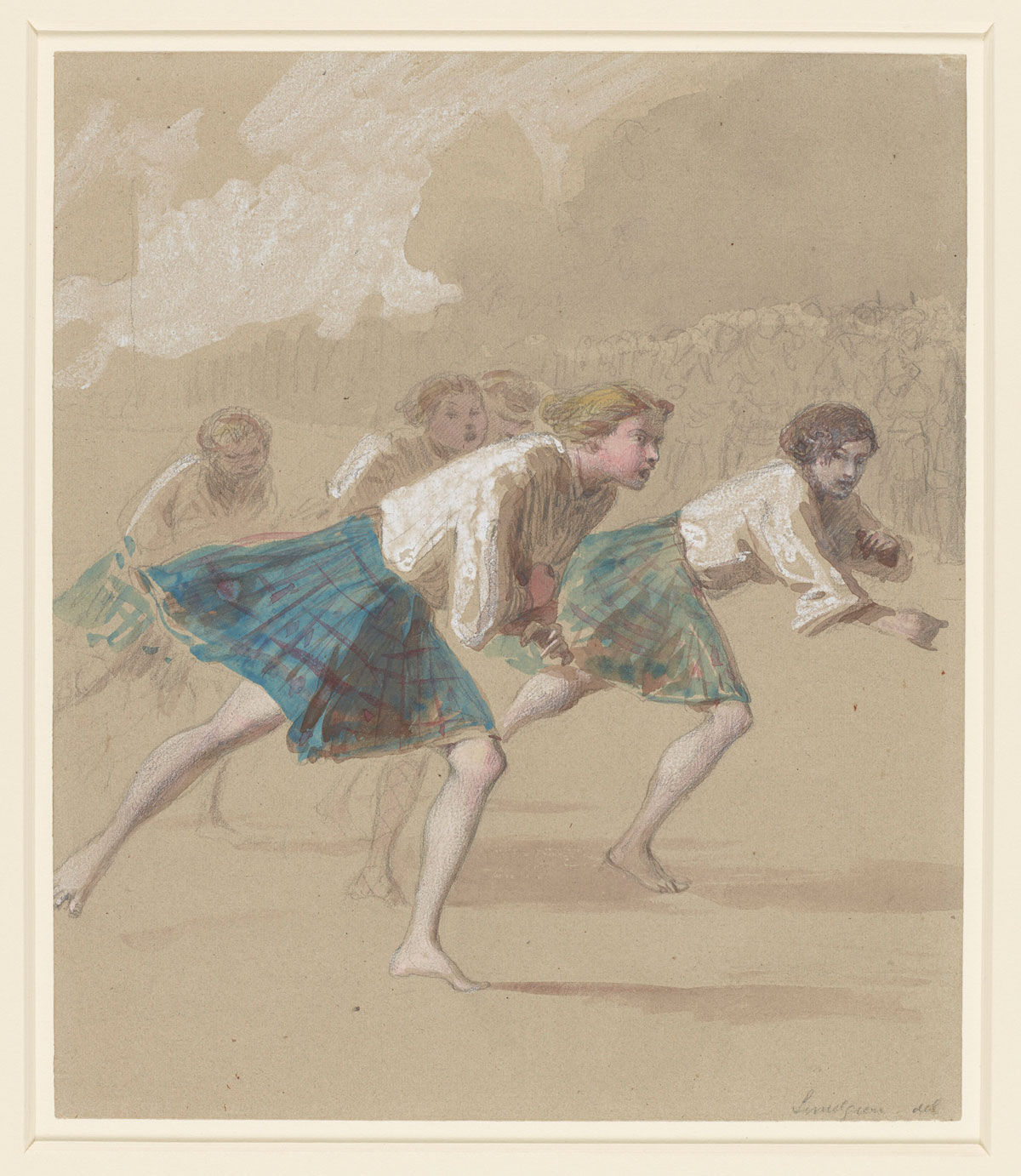

In order to explore the importance of imagery of local people in detail, I will focus on two illustrations of Highland Games that appear in the journal: ‘Highlanders Racing’ depicts the uphill race to Craig Cheunnich at the Braemar Gathering, begun in 1826 by the Braemar Highland Society (Fig. 10), while ‘Tossing the Caber’ depicts an event common to most Highland Games (Fig. 11). This particular event was part of a fete thrown by Queen Victoria on 22 September 1859 for delegates to the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science at Aberdeen, where Prince Albert would give an address as the president (Weintraub, p. 376).

‘Highlanders Racing’ and ‘Tossing the Caber’ were both provided by Egron Lundgren, a Swedish-born artist whose career was distinguished in part by his long-standing association with Queen Victoria. Like Haag, Lundgren was a peripatetic artist: while in Spain in the late 1840s he befriended English visitors, including the artist John ‘Spanish’ Philip and Lady Louisa Tenison, who later invited him to London. Like Haag he was a foreign artist drawn to the vibrant and cosmopolitan artistic scene in London and the promise of aristocratic patronage. He arrived in 1855 and, soon after, royal patronage seemed to secure his future success as a watercolour painter and sketch artist.45 The Queen’s patronage of Lundgren suggests that she understood that the spheres of art and graphic journalism were interconnected.

The Queen invited Lundgren to spend three weeks with the royal family at Balmoral in September 1859.46 While there, he observed the Highland Games, the Gillies’ Ball, and deer stalking. He seemed fascinated by the crowd at the games staged for the British Association for the Advancement of Science (Figs. 12, 13), producing numerous sketches of top-hatted gentlemen and ladies in bonnets clustered together. He seems to position himself both within the crowd and apart from it. For example, in Lundgren’s watercolour sketch Putting the Weight (see Fig. 13), the bent figure of the athlete becomes lost in a crowd that is divided in two: Highland figures on the right and genteel observers on the left. A blank area in the centre creates a void that separates them indefinitely. In the more finished watercolours that he produced for the Queen, Lundgren keeps the crowd in the picture, as in Tossing the Caber (Fig. 14). Yet when this scene appears in Leaves (see Fig. 11), the crowd vanishes, leaving only the athlete to perform his feat of physical prowess against a mottled grey backdrop that creates the illusion of space against the white page.

Although executed in the medium of reportage, the engravings after Lundgren’s sketches produce the same temporal suspension created by Haag’s illustrations, in that they depict events that do not relate directly to those described in the text. Although Lundgren completed the watercolour on which this engraving is based in 1859 (Fig. 15), the image ‘Highlanders Racing’ (see Fig. 10) is placed in the text in proximity to the Queen’s recollection of the Braemar Gathering of 1850, when her gillie Duncan won the event. The Queen in 1850 treats the race as part of the picturesque landscape, recalling, ‘it looked very pretty to see them run off in their different coloured kilts, with their white shirts’ (Leaves, p. 77). However, her comments upon the race in 1859, the same one Lundgren observed, have a different tone: ‘the scene [was] wild and striking in the extreme. […] [We] returned to the upper terrace to see the race, a pretty wild sight’ (Leaves, p. 166). The sketch, highlighted by watercolour and body colour, conveys the physical exertion of the race through the strained body posture and the focused attention of the central figure. The plaid of the flying kilts dissolves into a loose cross-hatching in the background, and the engraver Cooper had to fill in details of dress and expression to render the scene credible.

It is instructive to compare these sketches and watercolours with those Lundgren made during his time in India. The rebellion had begun on 10 May 1857, when sepoys in the army of the East India Company stationed in Meerut mutinied; other military and civilian rebellions followed. The British army had retaken Lucknow in December 1857 and Gwalior in June 1858. Lundgren witnessed the frantic and brutal efforts by British troops to quell the final stages of the Indian Rebellion, sweeping across the northern plains.

The rebellion and its aftermath was a seminal moment for the formation of the British Empire. In August the administration of India passed from the East India Company to the Crown. For many, this move signalled not only the end of the rebellion but also a new chapter in the relationship with India, the birth of the British Raj.47 At this same moment, racial theory began to structure Britain’s relationship to its empire, and the British Association for the Advancement of Science explored this topic, alongside the Anthropological Society and the Ethnological Society.48 Lundgren’s work in India suggests that he understood these terms, noting in a letter that he viewed the conflict as one between ‘the Hindu and Anglo-Saxon races’ (Nilsson and Gupta, p. 57).

Lundgren befriended the pioneering war correspondent William Howard Russell and they travelled with Sikh cavalry and infantry brigades.49 Punjabi Sikhs and Gurkhas from Nepal came to be regarded as ‘martial races’, who, alongside the Highlanders of Scotland, were ‘linked in both popular and military discourse as the British Empire’s fiercest, most manly soldiers’.50 Although Lundgren does not depict the Highland regiments, their presence was firmly etched in his memory: after the fighting, he heard a Scottish piper in the distance playing sentimental and traditional tunes: ‘Home Sweet Home’ and ‘Annie Laurie’ (Lundgren, II, 176).

Lundgren’s Five Sikhs and Gurkhas brings together different soldiers to illustrate facial characteristics as a defining feature of racial difference, in contrast to the more generalizing approach of his Highland Games sketches (Fig. 16). He depicts each figure from a slightly different angle with careful attention to details of dress as well as weaponry. Although he likely based these paintings on a hybrid of visual sources, combining observations of real sitters while drawing from the popular physiognomic literature of the period, watercolours such as this one communicate a seriousness of purpose to these figures befitting their status as warriors and allies.51

Such differentiation through physical characteristics was a vital part of the mid-Victorian interest in racial classification, a practice promoted by the British Association. According to Mary Cowling, images such as these participated in ‘the public exchange of ideas and assumptions about human types, providing a means of visual embodiment and helping give credence to them with each example’.52 The day before the tossing of the caber, delegates at the meeting of the British Association heard presentations on Nepalese phrenology, Aboriginal Australians, and commerce in British India after Prince Albert’s opening remarks invited them to consider ‘the wild and primitive’ Highlands.53 Albert’s formulation expresses the ways in which otherness, whether it be within or without the boundaries of the nation, were so closely tied, as George Stocking has observed.54

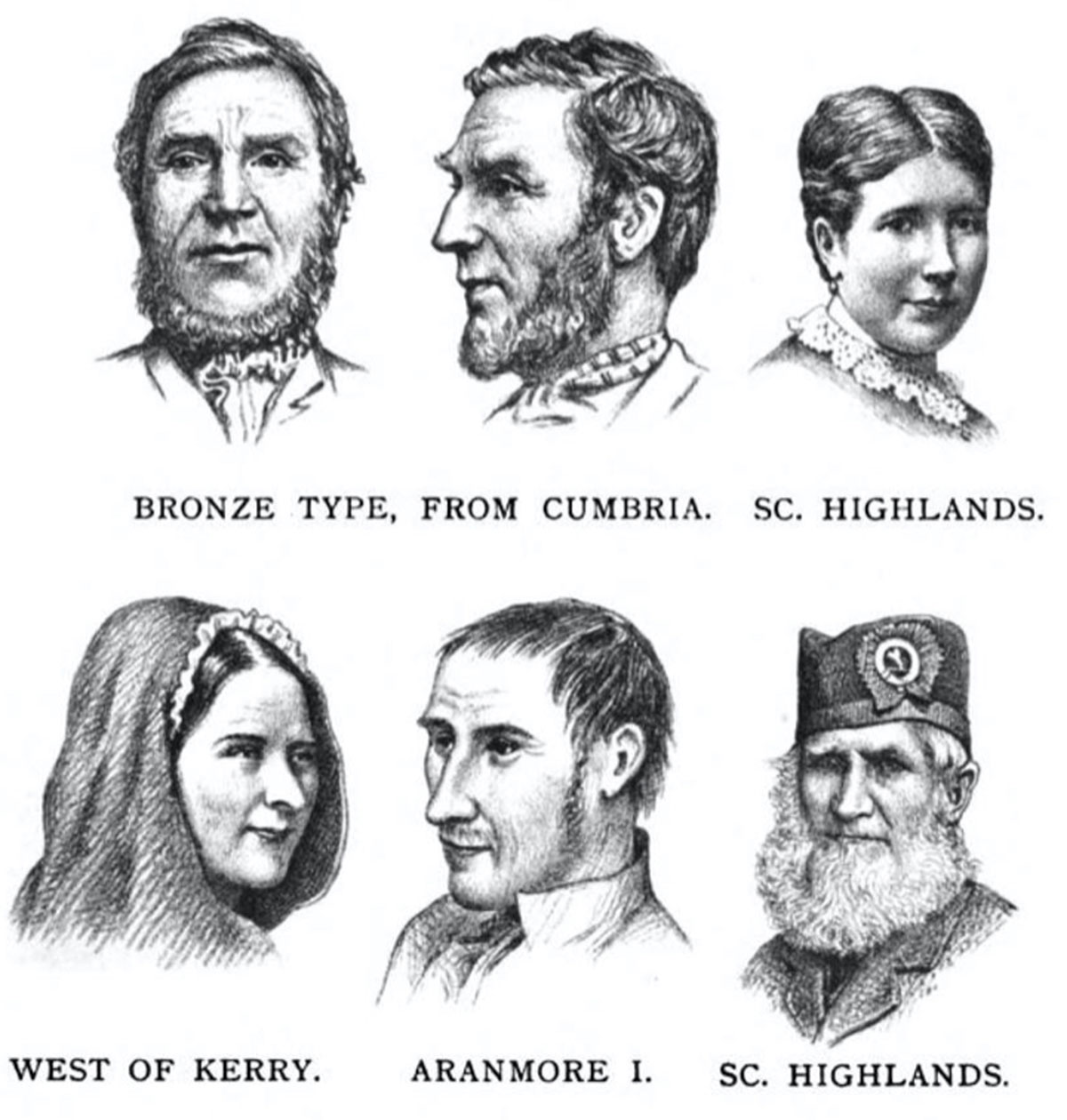

John Beddoe, one-time president of the Anthropological Society of London, was one of the pioneers in this field.55 In his Contribution to Scottish Ethnology (1853), later combined with other work and expanded as The Races of Britain (1885), he examined cephalic indices (the ratio of skull breadth to length) and skin pigmentation to devise an ‘index of nigrescence’, whereby he determined which races were closer to Africans than to Anglo-Saxons.56 The Highland areas of Scotland, alongside Ireland, had a higher nigrescence index, an assertion that Beddoe supports with a series of representative heads (Fig. 17). Beddoe points the reader’s attention to the prominent brow-ridge on the disembodied head of the elderly man labelled ‘Sc. Highlands’ (the receding forehead, another sign of Highland nigrescence, is hidden under the glengarry). This old man from Clan Mackintosh is an exemplary type, a representative who stands in for his race.57

The delegates of the British Association would have had an opportunity for cephalic study when they witnessed the brute force of physical exertion seen in Lundgren’s Tossing the Caber (see Fig. 14). The athlete grimaces as he braces a tree trunk against his kilt-clad knee and prepares to hurl it into the air. In addition to his prominent brow-ridge, this Highlander has the hunched back and long arms usually reserved for caricatured depictions of non-white natives or the Irish.58 In this sense these engravings negotiate a place for the Highlander within a larger conception of British identity through the presentation of the Highlander in racial, rather than cultural, terms, a mode of presentation that recalls efforts to catalogue diverse imperial natives such as John Forbes Watson and John William Kaye’s photographic study The People of India (1868–75).59 While Watson and Kaye used caste as the organizing principle in their effort to produce ‘typical’ representations, Lundgren uses the Highland Games. His images articulate the difference between the Highlander and the non-Highlander, while domesticating that difference into a non-threatening version of Highland identity and Highland culture.

Conclusion: illustrated print culture and the politics of representation

I began this article by asking whether the Highlands could represent, in the Victorian pictorial imagination as distilled in the Leaves, a form of colonial uncanny, a place that was at once ‘home’ and ‘away’. The answer is ‘yes’ to both. For example, the absence of any mention of the Indian Rebellion from Leaves would suggest that such an ‘entanglement’ was damaging to ideas of nation as well as home. The complicated politics of imperial representation emerge, for example, with the arrival of the Swedish artist Egron Lundgren at Balmoral in 1859, directly from India where he had sketched the aftermath of the rebellion at the request of the Queen. His illustrations suggest the ways in which representation can elide experiences, making what is not pictured the subject of the picture. The abundance of illustrations in the Christmas edition of Leaves suggests this representational paradox, as proliferating images of Prince Albert, for example, memorialize his absence. Furthermore, when considered as ‘illustrated print culture’ rather than as illustrations, the images in Leaves aptly demonstrate their ‘image value’, drawing upon a diverse range of visual vernaculars and graphic techniques to represent royal family life in the Highlands. Proliferating and multivalent in technique, subject matter, and style, they register uncertainty and contradiction in their construction of the royal family, of nation, and of empire.

Notes

- As discussed in, for example, David Duff, Victoria in the Highlands (London: Muller, 1968); and Tyler Whittle, Victoria and Albert at Home (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980). For artists at Balmoral, see Delia Millar, Queen Victoria’s Life in the Scottish Highlands: Depicted by Her Watercolour Artists (London: Wilson, 1985); as well as John Morrison, ‘“The whole is quite consonant with the truth”: Queen Victoria and the Myth of the Highlands’, in Victoria and Albert: Art and Love: Essays from a Study Day Held at the National Gallery, ed. by Susanna Avery-Quash (London: Royal Collection Trust/HM Queen Elizabeth II, 2012) <https://www.rct.uk/sites/default/files/V%20and%20A%20Art%20and%20Love%20%28Morrison%29.pdf> [accessed 16 November 2021]. [^]

- Your Dear Letter: Private Correspondence of Queen Victoria and the Crown Princess of Prussia, 1865–1871, ed. by Roger Fulford (London: Evans Brothers, 1971), p. 166. [^]

- There was also a version of Leaves illustrated with landscape photographs by George Washington Wilson. See Lucien Goldschmidt and Weston J. Naef, The Truthful Lens: A Survey of the Photographically Illustrated Book, 1844–1914 (New York: Grolier Club, 1980), p. 205. [^]

- See Rebecca Steinitz, Time, Space, and Gender in the Nineteenth-Century British Diary (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) for the Queen’s interest in sales figures (p. 139). According to John Plunkett, the Penny Satirist and the Spectator suggested that the Queen publish accounts of her travels as early as 1848 based on her popularity and influence, especially with her female subjects. See John Plunkett, ‘Of Hype and Type: The Media Making of Queen Victoria, 1837–1845’, Critical Survey, 13.2 (2001), 7–25. [^]

- See ‘Current Literature: Christmas Books’, Spectator, 26 December 1868, pp. 1544–45 (p. 1544). For publication details of various editions, see Samuel Austin Allibone, A Critical Dictionary of English Literature, and British and American Authors Living and Deceased (London: Trübner, 1871), p. 2523. As Pamela Fletcher has noted, the marketing of gift books at Christmas in the 1860s shifted to a focus on illustrations. See Pamela Fletcher, ‘Illustration’, in Allen Staley and others, The Post-Pre-Raphaelite Print: Etching, Illustration, Reproductive Engraving and Photography in England in and around the 1860s (New York: Mirian & Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University, 1995), pp. 37–39 (p. 38). [^]

- Most of these vignettes depict Highland scenery and architecture: forty-seven views of castles, lochs, and glens in total, including some after drawings by Queen Victoria. For sketches by Victoria, see Marina Warner, ‘Queen Victoria as an Artist: From Her Sketchbooks in the Royal Collection’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 128 (1980), 421–36. Space here does not permit me to address the representation of the Highland landscape in the journal and the ways in which these images intersect with broader debates about landscape, nation, and empire. For further consideration of these themes in relationship to representation of the Scottish landscape, see John Morrison, Painting the Nation: Identity and Nationalism in Scottish Painting, 1800–1920 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003); as well as John Morrison, ‘Highlandism and National Identity’, in A Shared Legacy: Essays on Irish and Scottish Art and Visual Culture, ed. by Fintan Cullen and John Morrison (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005), pp. 97–112. Instead, I will focus my attention on those illustrations that depict Highland activities. [^]

- Patricia Mainardi, Another World: Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Print Culture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), pp. 1, 8. [^]

- Barbara Leckie, ‘On Print Culture: Mediation, Practice, Politics, Knowledge’, Victorian Literature and Culture, 43 (2015), 895–907. Leckie expands on the discussion begun by Laurel Brake, ‘On Print Culture: The State We’re In’, Journal of Victorian Culture, 6 (2001), 125–36. Linda Hughes has recently called for ‘sideways’ moves in the investigation of print culture, calling for a methodology that considers not only material form but also the web of associations that link text to text and text to audience, as well as ‘local formations’. See Linda K. Hughes, ‘SIDEWAYS!: Navigating the Material(ity) of Print Culture’, Victorian Periodicals Review, 47 (2014), 1–30 (p. 5). [^]

- W. J. T. Mitchell, What Do Pictures Want?: The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), p. 47. [^]

- Margaret Homans, Royal Representations: Queen Victoria and British Culture, 1837–1876 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), especially pp. 131–45; as well as Adrienne Munich, Queen Victoria’s Secrets (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996); and Steinitz, pp. 136–50. [^]

- See R. H. Campbell and T. M. Devine, ‘The Rural Experience’, in People and Society in Scotland, ed. by T. M. Devine and others, 3 vols (Edinburgh: Donald, 1988–92), II: 1830–1914, ed. by W. Hamish Fraser and R. J. Morris (1990), pp. 290–309. [^]

- Peter Womack, Improvement and Romance: Constructing the Myth of the Highlands (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1989), p. 148. See also, Charles Withers, ‘The Historical Creation of the Scottish Highlands’, in The Manufacture of Scottish History, ed. by Ian Donnachie and Christopher A. Whatley (Edinburgh: Polygon, 1992), pp. 143–56. [^]

- See, for example, the essays collected in The Victorian Illustrated Book, ed. by Richard Maxwell (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2002). [^]

- See Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, Poetry, Pictures, and Popular Publishing: The Illustrated Gift Book and Victorian Visual Culture, 1855–1875 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2011). [^]

- As discussed in Colette Colligan and Margaret Linley, ‘Introduction: The Nineteenth-Century Invention of Media’, in Media, Technology, Literature in the Nineteenth Century: Image, Sound, Touch, ed. by Colette Colligan and Margaret Linley (Farnham: Ashgate, 2011), pp. 1–20. [^]

- Your Dear Letter, ed. by Fulford, p. 166. [^]

- John Plunkett, Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); and John Plunkett, ‘Civic Publicness: The Creation of Queen Victoria’s Royal Role 1837–61’, in Encounters in the Victorian Press: Editors, Authors, Readers, ed. by Laurel Brake and Julie F. Codell (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp. 11–28. [^]

- As an advertisement for the volume states: ‘The Illustrations have been selected, by the Royal permission, from the Private Collection of Her Majesty, and comprise Eight Engravings on Steel, from Pictures by Sir Edwin Landseer, R. A., Carl Haag, and other Artists. Two Interior Views of Balmoral, in Chromo-lithography, and upwards of 60 highly-finished Engravings on Wood of Scenery, Places, and Persons mentioned in the work. The Queen has also been pleased to sanction the introduction of a few Fac-similes of Sketches by Her Majesty’ (Allibone, p. 2523). [^]

- Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose, ‘Introduction: Being at Home with the Empire’, in At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World, ed. by Catherine Hall and Sonya O. Rose (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), pp. 1–31 (p. 1). [^]

- The chosen frontispiece for the illustrated journal was an engraving entitled ‘Balmoral Forest, 1860 (The Prince Consort, and the Queen in the Distance)’ after a chalk and pastel drawing by Sir Edwin Landseer. See Delia Millar, The Victorian Watercolours and Drawings in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, 2 vols (London: Wilson, 1995), I, 522–24. The portrait of the prince is a posthumous one, commissioned by the Queen in 1865 to commemorate an event from 1860. Landseer did not complete it until August 1867 due to negotiations over the size of the work and the likeness of the prince. For Queen Victoria and Landseer, see Trevor Pringle, ‘The Privation of History: Landseer, Victoria, and the Highland Myth’, in The Iconography of Landscape: Essays on the Symbolic Representation, Design and Use of Past Environments, ed. by Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), pp. 142–61; as well as Richard Ormond, The Monarch of the Glen: Landseer in the Highlands (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2005), pp. 120–25. [^]

- As discussed in Walter Karbach, Carl Haag: Victorian Court Painter and Travelling Adventurer between Orient and Occident, trans. by Ruth Whiteley (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019), pp. 81–89. My discussion of Haag and his work is indebted to Karbach’s research. [^]

- See Frances Dimond and Roger Taylor, Crown & Camera: The Royal Family and Photography, 1842–1910 (London: Viking, 1987), pp. 13–16. For an overview of Becker’s interest in photography, see Hans Christian Adam, ‘A German at Queen Victoria’s Court: Ernst Becker’s Albums’, PhotoResearcher, 31 (2019), 64–75. [^]

- Notes to Becker record that the Queen requested such enlargements (‘die Vergrößerung’) from him. See, for example, Dr. Ernst Becker, Briefe aus einem Leben im Dienste von Queen Victoria und ihrer Familie, ed. by Lotte Hoffman-Kuhnt (Plaidt: Cardamina, 2014), p. 572, n. 71. [^]

- While Morning depicts a royal party ascending Lothnagar (Prince Albert, followed by Princess Alice, Prince Alfred, Queen Victoria, the Princess Royal, the Prince of Wales, and the governess Miss Bulteel, with gillies), Evening shows the return of a hunting party made up of John Brown (with torch in the right foreground), Prince Albert, the Earl of Aberdeen, Sir Charles Phipps, and to the right, Count Alexander Mensdorff and Lt Col Alexander Gordon. As detailed in Jonathan Marsden and others, Victoria and Albert: Art & Love (London: Royal Collection Enterprises, 2010), p. 210, nn. 128–29. [^]

- Maureen M. Martin, The Mighty Scot: Nation, Gender, and the Nineteenth-Century Mystique of Scottish Masculinity (Albany: SUNY Press, 2009), pp. 5, 8. [^]

- All text citations from the journal are taken from Victoria, Queen of Great Britain, Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, ed. by Arthur Helps, illustrated edn (New York: Harper, 1868), p. 73. [^]

- Leaves, p. 128. Many debates, scholarly and otherwise, exist concerning the exact nature of the Queen’s relationship to John Brown. For this discussion in its various forms, see Tom Cullen, The Empress Brown: The Story of a Royal Friendship (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1969); and E. E. P. Tisdall, Queen Victoria’s Mr. Brown: The Life Story of the Most Remarkable Royal Servant in British History (New York: Stokes, 1938). For a more measured discussion of the relationship and its effects on the Queen’s public image, see Dorothy Thompson, Queen Victoria: Gender and Power (London: Virago, 1990); and Richard Williams, The Contentious Crown: Public Discussion of the British Monarchy in the Reign of Queen Victoria (Brookfield: Ashgate, 1997). [^]

- As discussed in Stanley Weintraub, Uncrowned King: The Life of Prince Albert (New York: Free Press, 1997); as well as Homans, esp., pp. 1–43. [^]

- For the kilt’s place in the construction of Highland identity, see Hugh Trevor-Roper, ‘The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland’, in The Invention of Tradition, ed. by Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1983), pp. 15–42; as well as Hugh Trevor-Roper, The Invention of Scotland: Myth and History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008). [^]

- Soon after the trip to Balloch Buie in 1848, Macdonald would leave Balmoral service and become keeper of the royal stables at Windsor Castle, where he did not wear Highland dress. As noted in My Mistress the Queen: The Letters of Frieda Arnold Dresser to Queen Victoria, 1854–9, ed. by Benita Stoney and Heinrich C. Weltzein, trans. by Sheila de Bellaigue (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1994), p. 46. Presumably, given the date of the photograph, he would continue to join the royal family at Balmoral, at least in 1854. Throughout the 1850s, Queen Victoria had a number of her Highland household staff photographed by Wilson and Hay, as well as by Thomas Pearce. A note from Victoria to Ernst Becker attests to her interest in these photographs, asking him to talk to ‘Mr. Pearce’ about obtaining photographs of John Grant (1810–1879), Charles Duncan (1826–1904), Donald Stewart (1827–1909), John Brown (1827–1883), John Mackenzie, Peter Farquharson (the son of her servant Arthur Farquharson, photographed by Wilson and Hay), and Johnnie Grant (the son of John Grant). These instructions probably date from 1855. See Dr. Ernst Becker, ed. by Hoffman-Kuhnt, p. 566, n. 28. In the case of George Washington Wilson and his partner John Hay, Queen Victoria would continue this patronage with a commission to record the construction of Balmoral. [^]

- A number of publications supported this goal, including the illustrated fine arts coverage in the Illustrated London News and the Graphic, which first appeared in 1869. See Celina Fox, Graphic Journalism in England during the 1830s and 1840s (New York: Garland, 1988), p. 7. See also, Patricia Anderson, The Printed Image and the Transformation of Popular Culture, 1790–1860 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), p. 22. [^]

- As explained in Antony Griffiths, The Print before Photography: An Introduction to European Printmaking, 1550–1820 (London: British Museum, 2016), p. 489; and Richard Benson, The Printed Picture (New York: MoMA, 2009), pp. 36–39. [^]

- Haag would return to Balmoral intermittently from 1863 to 1865 to complete a number of works for the Queen that memorialized Prince Albert and his affection for the Highlands, including the elegiac watercolour The Queen and the Prince Fording the Poll Tarf. See Karbach, pp. 172–92. [^]

- As discussed in Briony Llewellyn, ‘Observations and Interpretations: Travelling Artists in Egypt’, in Black Victorians: Black People and British Art, 1800–1900, ed. by Jan Marsh (London: Lund Humphries, 2005), pp. 35–45, 132. [^]

- Charles W. J. Withers, Gaelic Scotland: The Transformation of a Culture Region (London: Routledge, 1988), p. 143. See also Neil Davidson, The Origins of Scottish Nationhood (London: Pluto, 2000); and Colvin Kidd and James Coleman, ‘Mythical Scotland’, in The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History, ed. by T. M. Devine and Jenny Wormald (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), pp. 62–77; as well as Trevor-Roper, ‘The Invention of Tradition’, and The Invention of Scotland. [^]

- Michael Hechter, Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development, 1536–1966 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975). Hechter asserts that the process of ‘internal colonialism’ followed throughout the eighteenth century, whereby ‘the several local and regional cultures [were] gradually replaced by the establishment of one national culture which cuts across previous distinctions’ (p. 5, emphasis in original). By Celtic areas, Hechter means areas where Gaelic or Celtic was the indigenous language; namely, the Highlands of Scotland and Ireland. As Maureen Martin notes, ‘as an internal colony, Scotland (identified with the Highlands) remained a primitive other that helped define English civilization, but at the same time was embraced as an intrinsic part of Englishness’ (p. 4). [^]

- See, for example, David Armitage, ‘Making the Empire British: Scotland in the Atlantic World, 1542–1707’, Past and Present, 155 (1997), 34–63; and the edited collection, Scotland and the British Empire, ed. by John M. MacKenzie and T. M. Devine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011). For a different perspective, see Onni Gust, ‘Remembering and Forgetting the Scottish Highlands: Sir James Mackintosh and the Forging of a British Imperialist Identity’, Journal of British Studies, 52 (2013), 615–37. Historian Robert Clyde has described this process as the transition ‘from rebel to hero’ in the early nineteenth century. See Robert Clyde, From Rebel to Hero: The Image of the Highlander, 1745–1830 (East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 1995). [^]

- Murray G. H. Pittock, The Invention of Scotland: The Stuart Myth and the Scottish Identity, 1638 to the Present (London: Routledge, 1991), p. 100. [^]

- John Barrell, The Infection of Thomas De Quincey: A Psychopathology of Imperialism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), p. 10, emphases in original. [^]

- Sigmund Freud, ‘The Uncanny’ (1919) <https://web.archive.org/web/20110714192553/http://www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~amtower/uncanny.html> [accessed 17 November 2021]. [^]

- Mary Louise Pratt, ‘Scratches on the Face of the Country; or, What Mr. Barrow Saw in the Land of the Bushman’, in ‘Race’, Writing and Difference, ed. by Henry Louis Gates, Jr (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989), pp. 138–62 (p. 139). [^]

- Egron Lundgren, En målares anteckningar: Utdrag ur dagböcker och bref, 3 vols (Stockholm: Norstedt, 1872), II: Indien, 1: ‘åtskilligt arbete för Hennes Majestät, en ynnest hvaraf jag kunde vänta mig oberäknelig fördel’ (‘[I received] this gracious mission from the Queen to carry out work for her on this journey, a recognition that would put me at an advantage’, author’s own translation.) <http://runeberg.org/lemalares/2/0005.html> [accessed 17 November 2021]. The Queen’s decision to send Lundgren to record these events was probably modelled on Agnew’s endeavour with the photographer Roger Fenton, who produced views of the Crimean War that appeared as Photographic Pictures of the Seat of War in Crimea in late 1855. [^]

- As noted in My Mistress the Queen, ed. by Stoney and Weltzein, p. 191. [^]

- The planned book was never published but Lundgren’s sketches were used by the artist Thomas Jones Barker for his oil painting The Relief of Lucknow, 1857, now known only from a second version in the National Portrait Gallery in London and prints after the painting. For Lundgren’s sketches, see Sten Nilsson, ‘Egron Lundgren, Reporter of the Indian Mutiny’, Apollo, 92 (1970), 138–43. These drawings were shown again at Agnew’s alongside Barker’s painting in May 1860 to advertise the publication of the print. [^]

- He received commissions from Queen Victoria to record life at court and other events of interest to her, including theatrical performances, some of which were later reproduced in the Illustrated London News. He exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1862, and he became a member of the Old Water Colour Society in 1865. See Sten Nilsson and Narayani Gupta, The Painter’s Eye: Egron Lundgren and India (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1992), pp. 21–22. See also Delia Millar, ‘Watercolours Painted by Egron Lundgren for Queen Victoria’s Theatrical Album’, in Egron Lundgren, en målares anteckningar, ed. by Küllike Montgomery (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1995), pp. 57–70. [^]

- In a letter from 29 September 1859, Lundgren notes that he does not know how long the Queen will ask him to remain at Balmoral. Los Angeles, Getty Research Institute, 2005.M.21. [^]

- Priti Joshi, ‘1857; or, Can the Indian “Mutiny” Be Fixed?’, BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History, ed. by Dino Franco Felluga <http://www.branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=priti-joshi-1857-or-can-the-indian-mutiny-be-fixed> [accessed 17 November 2021]. See also, Gautam Chakravarty, The India Mutiny and the British Imagination, Cambridge Studies in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture, 43 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). [^]

- Ronald Rainger, ‘Race, Politics, and Science: The Anthropological Society of London in the 1860s’, Victorian Studies, 22 (1978), 51–70; as well as Robert J. C. Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture, and Race (London: Routledge, 1995); and C. C. Eldridge, The Imperial Experience: From Carlyle to Forster (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1996). [^]

- Lundgren also contributed illustrations to My Diary in India, published in 1860 by William Howard Russell. It is likely that Russell befriended Lundgren upon his arrival in India in 1858 as the artist eagerly pursued connections that could extend his access in the country. See William Howard Russell, My Diary in India, in the Year 1858–9 (London: Routledge, Warne, and Routledge, 1860). Lundgren also provided the illustrations for the memoir of Axel Lind af Hageby, a Swedish adventurer who fought with the British army during the Indian Rebellion. See Axel Lind af Hageby, Minnen från ett tre-årigt vistande i engelsk örlogstjänst 1857–1859 (Stockholm: Bonniers, 1860). [^]

- Heather Streets, Martial Races: The Military, Race and Masculinity in British Imperial Culture, 1857–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004), p. 1. [^]

- One possible model for Lundgren’s work was Colesworthy Grant’s Sketches of Oriental Heads: Being a Series of Lithographic Portraits Drawn from Life, Intended to Illustrate the Physiognomic Characteristics of the Various People and Tribes of India (1838–50). Grant would often depict front and profile views of the same sitter, as in his portrait of one ‘Sunaee Singh’ from the 1844 edition, suggesting his adherence to Johann Casper Lavater’s belief that the profile provides valuable information about character. See Johann Casper Lavater, Essays on Physiognomy, 3rd edn (London: Blake, 1840), pp. 148–49. In fact, the Indian Rebellion gave new life to Grant’s images, as the Illustrated London News reproduced his ‘sketches’ in their coverage of the first weeks of the rebellion, before eyewitness visual accounts could reach London. See, for example, ‘Bengal Sepoys — From C. Grant’s “Oriental Heads”’, Illustrated London News, 22 August 1857, p. 185. [^]

- Mary Cowling, The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and Character in Victorian Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. xix. [^]

- ‘Address by His Royal Highness the Prince Consort’, in Report of the Twenty-Ninth Meeting of the British Association of the Advancement of Science (London: Murray, 1860), pp. lix–lxix (p. lx). [^]

- George Stocking points out the ‘close articulation, both experiential and ideological, between the domestic and the colonial spheres of otherness’. See George W. Stocking, Jr, Victorian Anthropology (New York: Free Press, 1987), p. 235. [^]

- Beddoe’s project is part of what Graeme Morton has described as the ‘objectification’ and ‘self-objectification’ of Scotland throughout the nineteenth century, one of many systems of ‘classification’ that formed the popular idea of ‘the national self’. See Graeme Morton, Ourselves and Others: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012), p. 15. [^]

- As discussed in Heather Winlow, ‘Anthropometric Cartography: Constructing Scottish Racial Identity in the Early Twentieth Century’, Journal of Historical Geography, 27 (2001), 507–28. [^]

- This engraving, likely done after a photograph, does reveal that the man wears a glengarry (a traditional Scottish bonnet) with the rampant cat of Clan Mackintosh, an ancient Scottish family. His glengarry features the rampant cat of their motto, ‘Touch Not This Cat Bot a Glove.’ I thank Paul Cowan for this information. [^]

- See L. Perry Curtis, Jr, Apes and Angels: The Irishman in Victorian Caricature, rev. edn (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1997) for a further discussion of this imagery, especially in relation to the Irish. [^]

- As discussed in Thomas R. Metcalf, Ideologies of the Raj, The New Cambridge History of India, III.4 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995). [^]