Queen Victoria, and the events that she was part of, were enthusiastically taken up by the shows, exhibitions, and lectures that blossomed in the nineteenth century.1 Although there were many ways that Victoria’s life was narrated, broadcast, depicted, and mythologized, shows and lectures played an increasingly significant role in civic life. They increasingly reached mass audiences through multiple local lectures and exhibitions. Cumulatively, they helped to forge the meaning of Victoria’s life and reign.

Versions of royal events were often replayed for show-going audiences. In July 1838 Astley’s Amphitheatre offered its ‘Coronation Pageant on Foot and Horseback’, while the Royal Surrey Theatre went so far as to purchase some of the coronation fittings from Westminster Abbey to use in its own ‘Grand Regal Festival’. Not to be outdone, Madame Tussaud’s was soon offering a waxwork tableau of Victoria in her coronation robes, flanked by the Duchess of Kent and the dukes of Sussex and Cambridge.2 Beyond circuses, waxworks, and theatre though, the early years of Victoria’s reign coincided with a proliferation of different moving-picture formats, which allowed audiences of all kinds, and in all parts of the nation, to vicariously experience royal events. Pictorial spectacle was ideal for capturing the grand pageantry and scale of such occasions.

Painted peep shows were de rigueur at rural and urban fairs, race days, and holy days, anywhere where a crowd would gather with a few pennies in their pocket; the showman would regale his audience with tableaux of the latest murder or royal occasion (or perhaps both!) (Fig. 1). Large touring panoramas also provided replayings of national royal events for regional audiences, while a variety of new handheld commemorative formats provided miniaturized versions of these spectacles.3 From the 1880s onwards, magic lantern lectures became commonplace as a means of combining education and entertainment, projecting hundreds of thousands of slides of every imaginable scientific, amusing, and educational subject, from travelogues and temperance tales to illustrated hymns and adaptations of popular fiction.4 Among the staple subjects of lantern lectures were biographical overviews of Victoria’s life and reign that linked her inextricably to the prosperity and advances of the period. Then, in the final years of her reign, British audiences experienced the cinematograph, its moving images simultaneously animated, projected, and photographic. The development of the British film industry was given a tremendous boost by public interest in its coverage of the Diamond Jubilee.5

Part of the attraction of nineteenth-century moving- and projected-image formats is undoubtedly proleptic, a seeming prefiguration of the ways that radio, cinema, television, and live broadcasting have continued to shape the experience of the British monarchy.6 The recent success of the historical biopics, Victoria (3 series, 2016–19) and The Crown (4 series, 2016–present), testify to the ongoing fascination with royal history.

As part of the bicentenary celebrations of Victoria’s birth at Kensington Palace in 2018, two unique shows were given to provide audiences with insights into the way that the Queen was pictured by the magic lantern and early film, the two dominant forms of popular exhibition in the final decades of the nineteenth century. Dr Jeremy Brooker, chair of the Magic Lantern Society, gave a magic lantern lecture that demonstrated the range of slides that would have been used to picture Victoria’s life and reign. Bryony Dixon, curator of silent film at the British Film Institute, gave a film show that brought to life the remarkable ways Victoria was captured by the cinematograph in the final years of her life. This article aims to give an experiential flavour of the royal films and lantern slides that would have been seen by Victorian audiences, setting them in the context of the broader ecology of exhibition culture by drawing on artefacts from the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum at the University of Exeter.

In the immediate decades before Victoria’s accession, touring panoramas became increasingly common as moving-image exhibitions. Unlike the fully circular 360-degree version, moving panoramas were scrolling canvases that were portable and which could be wound across a stage. The flamboyant coronation of George IV was thus the first to be taken up by the panorama form, much like the nascent film industry was given a boost by Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Charles Williams’s satirical print, ‘The Moving Panorama — or Spring Garden Rout’ (1823), pokes fun at the popular sensation created by Messrs Marshall’s panorama of the coronation of George IV, which was then being exhibited at the Great Room, Spring Gardens, London (Fig. 2). It was supposedly painted on 10,000 square feet of canvas and the moving canvas was accompanied by a ‘full military band, assisted by a finger organ and trumpets’.7 The print pokes fun at the crowd of eager picture-goers battling eagerly to see the show. Most of the throng have been disappointed and must wait in the street for the next performance; the numerous speech bubbles evoke their anticipation and excitement. One overenthusiastic attendee declares, ‘this is my seventh time of seeing it!!’; while another repeat spectator announces, ‘It was just the same when I was here last week, I think all the world mus [sic] come three times over.’ The audience itself becomes an animated panorama of motion, colour, noise, and spectacle.

Events from early in Queen Victoria’s reign, such as her coronation, marriage, and the opening of the Great Exhibition, were invariably marked by a range of pictorial replayings and domestic commemoratives. A panorama of her coronation could be found slowly wending its way from Dublin (where it was resident at the Circus, Lower Abbey Street, from October to December 1838) to Bristol and then onto Exeter (exhibiting from May to September 1839); it was still exhibiting in Leeds in March 1842, nearly four years after the event.8 At the Diorama in Regent’s Park, which offered enormous transforming tableaux, one of the new attractions of the 1839 season was a coronation picture that portrayed the moment Victoria was crowned.9

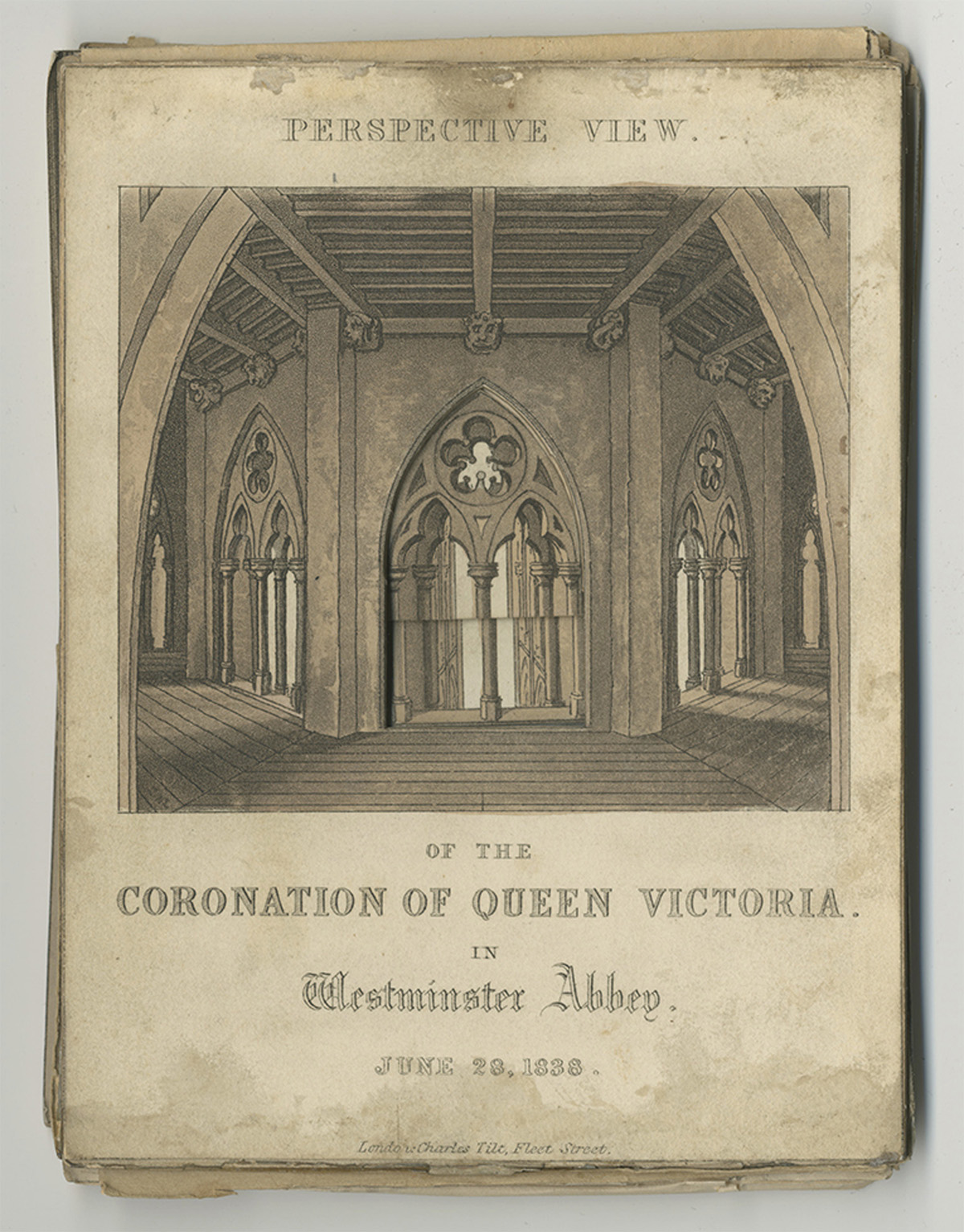

The crossover between the burgeoning worlds of optical exhibitions and popular publishing also resulted in a variety of small-scale devices. Supplementing the large-format panoramas were handheld versions, which could be unrolled, extended, or folded out to see whatever the lavish royal event was in all its spectacle, such as the extremely beautiful and expensive souvenir of the coronation, a scrolling panorama of the procession (Fig. 3), or a telescopic paper peep show version of the Westminster Abbey service that pulls out to 72 cm in length (Fig. 4). Both respective formats were ideal for capturing the extended moving pageant of such events.

The creative melting pot between popular exhibitions and print culture produced formats such as Spooner’s Protean Views — dioramic transforming prints popular in the late 1830s and through the 1840s. Like the larger Diorama at Regent’s Park, when the print was held up to a strong light source, a second hidden scene on the verso was revealed and seen through the surface print; thus, an empty Westminster Abbey slowly metamorphoses into one full of people showing Victoria being crowned (Fig. 5).10 Subsequent events such as the opening of the Great Exhibition continued to produce a similar plethora of moving-picture commemoratives.

Fig. 5: Morgan’s Dioramic View of the Coronation of Queen Victoria (London: Morgan, 1838). Courtesy of Bill Douglas Cinema Museum, University of Exeter.

Much has been written on Victoria and Albert’s interest in early photography as both art and science and on the success of the royal cartes de visite that were published from 1860 onwards.11 The advent of photography also encouraged the success of the stereoscope and magic lantern through photographic stereographs and lantern slides. Victoria herself was certainly no stranger to the magic lantern and panorama, or, indeed, to the burgeoning world of popular exhibitions in general. Her first recorded viewing of a panorama was during a visit to Covent Garden Theatre on 4 January 1833 when she was only thirteen. On a late night out seeing the pantomime Puss in Boots, she records that ‘We stayed till the panorama. We came home at 20 minutes past 12. I was soon in bed and asleep.’12 (Pantomimes often featured moving panoramas as part of their attractions.) Later the same year, Victoria visited the Colosseum in Regent’s Park, which had opened in 1827. Home to Thomas Horner’s enormous painted panorama of London, the viewer saw the metropolis from the top of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral (QVJ, 24 June 1833). Come the following pantomime season in December 1833, Victoria could again be found at Covent Garden for Old Mother Hubbard, noting that ‘the panorama at the end was also pretty’ (QVJ, 30 December 1833).

Following her marriage to Albert, Victoria continued to enjoy the shows of London, the couple usually going together and sometimes taking members of their young family. The Colosseum was a particular favourite, with Victoria and Albert visiting in May 1845 to sample the additional attractions; her children, Leopold, Arthur, Helena, and Louise, also visited as a birthday treat for Leopold in April 1857. In April 1849 Victoria went with her four eldest children and members of the royal household to see the latest sensation, a moving panorama of the Mississippi, ‘which was really very well painted by Mr Bauward, an American’.13 Victoria, Albert, and their four eldest children also enjoyed a visit to the Royal Polytechnic on Regent Street in 1855, the premier venue for popular science and spectacular lantern shows. Victoria enjoyed experiments on sound demonstrated by John Henry Pepper and a lantern show that she found ‘a rather long, though pretty illustration of the Voyages of Sinbad’ (QVJ, 10 May 1855).

Projecting Victoria — Jeremy Brooker and John Plunkett

Complementing the various trips to public exhibitions was the entertainment provided by domestic magic lantern shows, often delivered by Albert himself to his young family (Film 1). The lantern would have naturally appealed to Albert due to his interest in popular science and the arts. Magic lanterns were then enjoying a surge in usage (Film 2). Nonetheless, delivering a lantern show required a fair degree of technical competence, as well as affluence in order to purchase a well-made device.14 In November 1846 Albert purchased and experimented with a magic lantern, which was to be a present for the Princess Royal’s sixth birthday. When he delivered his show a week later, Victoria records that it ‘was a surprise for them, & with which they were delighted’ (QVJ, 21 November 1846). Several other royal lantern shows were given in the late 1840s and early 1850s. For the Prince of Wales’s thirteenth birthday in November 1854, he too received a magic lantern from his parents (QVJ, 9 November 1854). In her journal Victoria was still recording a magic lantern show given to her grandchildren in 1892 at Windsor, in this case for the sixth birthday of Prince Alexander Mountbatten.

Film 1: What is a magic lantern?

Film 2: How popular was the magic lantern?

The young royals were certainly fortunate, and to some degree exceptional, in the magic lantern shows they enjoyed in the 1840s and 1850s. Across British towns and cities, there were occasional public lantern lectures given by lecturers. There were grand spectacles on offer at the Royal Polytechnic in Regent Street and one or two other institutions of popular science; and lantern shows might well be given as part of special occasions such as Christmas or birthdays. However, it was not until the 1880s and 1890s that the lantern really took off as a means of public pictorial instruction. Unlike the sporadic appearances of the lantern in the first half of the century, when much of lantern hiring and exhibiting activity was associated with a small number of men interested in popular science (of whom Albert was one), lantern shows began to reach a genuinely mass audience on a routine basis. Lantern lectures were given on all possible subjects and to all manner of civic and special interest groups, and thus could be found at an extraordinary wide range of venues, including middle-class scientific societies and athenaeums, but also mechanics’ institutes, literary and historical societies, photographic societies, schools, churches, public halls, mission halls, workhouses, and variety theatres.

Lantern lectures devoted to the life and reign of Queen Victoria were a standard set in the repertoire of all major slide producers and distributors; individual lantern slides of Victoria were also often used within a larger show (Film 3). There was a plethora of different moving-effect slides that were created through using a ratchet, crank, lever, or just two pieces of glass pulled back and forth, as in the example of a British sailor dancing a hornpipe (Fig. 6).

Film 3: Queen Victoria and the magic lantern.

Fig. 6: Animated magic lantern slide of a sailor dancing a hornpipe, c. 1850. Jeremy Brooker collection.

Lantern lectures on Victoria were most likely to coincide with events such as the jubilees when public interest was at its height (Film 4). Equally, just as the royal children were treated with a lantern show to mark a special event, children at schools, workhouses, or church groups might well be given a magic lantern show for Christmas or to commemorate a national occasion like a royal wedding. The pattern of lantern lectures given in the UK was replicated across the burgeoning British Empire. For example, in the town of Merriwa, New South Wales, local children received a lantern show as part of the festivities for Victoria’s seventy-fifth birthday in May 1894.15 Similarly, in the city of Ipswich in Queensland, the Diamond Jubilee was celebrated with a public lantern lecture at the Wesleyan Church, given by Reverend Joseph Bowes from Brisbane. The audience was taken through Victoria’s life and reign; scenes included her coronation and marriage, her first visit to Scotland, Osborne House, the marriage of the Prince of Wales, and numerous jubilee scenes. Patriotic songs, including ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘Death of Nelson’, punctuated and supplemented the pictorial scenes, while the end of the lecture was marked by a collective singing of ‘God Save the Queen’ and three cheers for Victoria.16 After 1896 lantern lectures and touring panoramas were joined by early film shows in the exhibition landscape. Lantern and early film never existed in isolation; they reached similar audiences and venues; indeed, lantern shows often incorporated early film shorts as part of the evening’s entertainment and lantern lectures continued to be given in enormous numbers.

Film 4: Magic lanterns and the Diamond Jubilee.

Queen Victoria and early film — Bryony Dixon

From the first, film-makers were keen to film the Queen and any public or state events where she might appear. Moving pictures were the great novelty after photography and those who were charged with entertaining the royal household were eager to secure the Queen early sight of this new media. Early practitioners of the cinematograph were also more than aware of the benefits of royal patronage. There are twenty-nine films of Queen Victoria available to watch for free on the BFIplayer.

The first royal involvement with film came via the Prince of Wales; he visited the Alhambra Music Hall in June 1896 to see Robert Paul’s film of the Derby, which had been won by the prince’s own horse, Persimmon. Robert Paul had filmed the end of the race on 3 June when the crowd surged onto the course. The films were projected the next evening by his Animatograph and the Strand described them as being received with ‘wild enthusiasm, which all but drowned the strains of “God Bless the Prince of Wales”, as played by the splendid orchestra’.17 It was also the Prince of Wales rather than Victoria who was the first member of the British royal family to be filmed. He was recorded during a visit to the Cardiff exhibition on 27 June 1896 by the British film-maker, Birt Acres. The Prince of Wales was subsequently given a private show by Acres at Marlborough House on 21 July 1896, to a select audience that included guests for the wedding of Princess Maud, the prince’s youngest daughter.

It is no coincidence that court photographers were first off the mark in capturing Victoria herself. The moving images of early film also mark her continuing personal interest in new visual technologies and entertainment. She was first filmed at Balmoral in early October 1896 during a visit by Tsar Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra; the pictures were taken by J. Downey, son of William Downey, a long-standing court photographer who would be responsible for the official Diamond Jubilee photographic portrait (albeit actually taken in July 1893). Victoria’s journal describes being captured ‘by the new cinematograph process, which makes moving pictures by winding off a reel of films. We were walking up & down & the children jumping about’ (QVJ, 3 October 1896). The scenes were delightfully intimate and domestic — a family at leisure showing off for the latest novelty; we see the Queen in her pony trap, royal children and one of the Queen’s Indian attendants (Fig. 7).

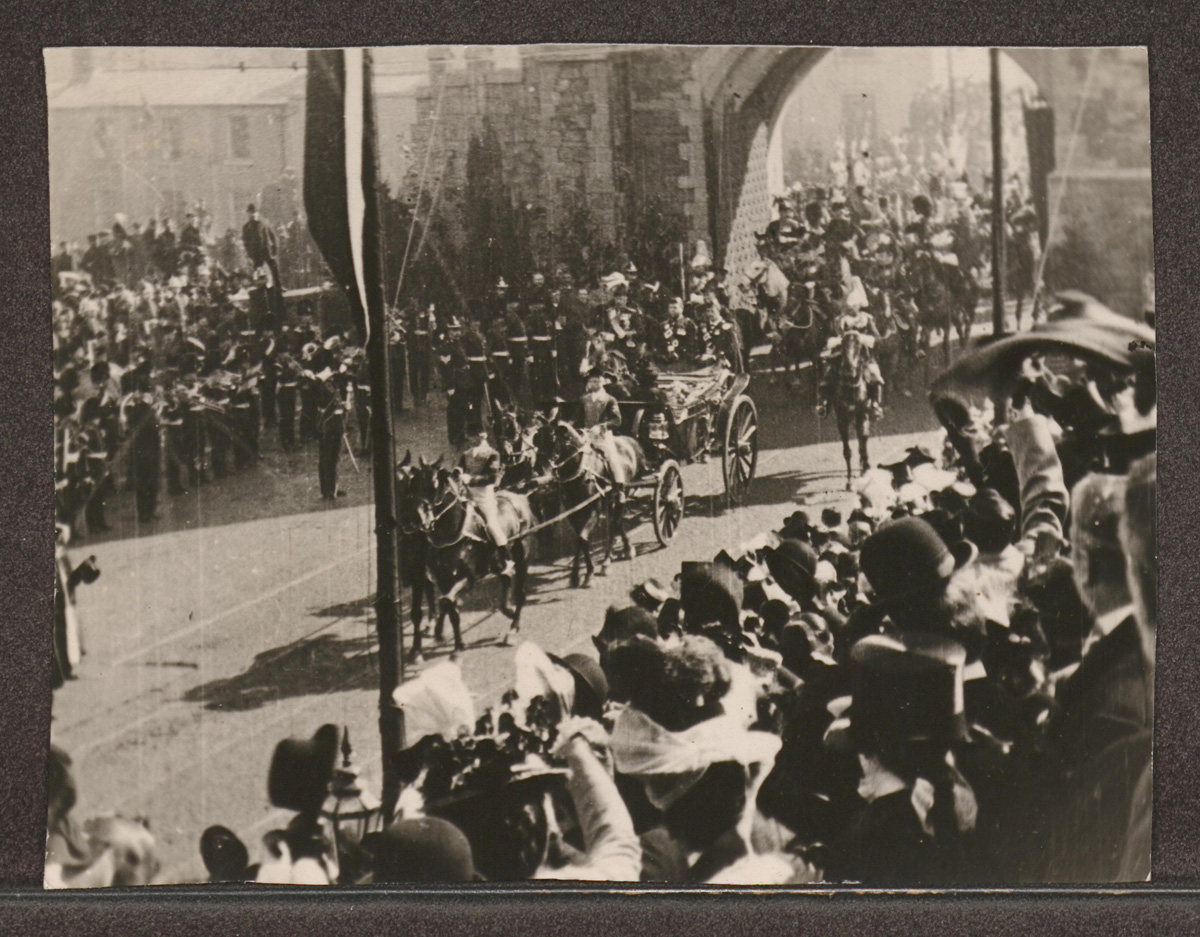

Films of the Queen were hugely popular with audiences worldwide for the remainder of her reign; the medium was highly successful at capturing the grand civic and ceremonial occasions that were intended to bring nation and empire together. Such was her standing in the world that she was the central figure in one of the seminal moments in the development of film, the Diamond Jubilee. The centrepiece of the celebrations was a grand military and imperial procession through London including troop detachments from many different colonies, and which attracted all the film companies then operating — French, American, and British — with the exception of Thomas Edison. These were circulated all over the globe for years afterwards. Forty cameramen took film, of which eleven fragments remain at the BFI National Archive.18 Robert Paul, Britain’s leading film producer, had several cameramen along the route; in one film he captured the royal carriage coming into St Paul’s churchyard. Another fragment, probably by Alfred Wrench, gives the best view of the Queen in the state landau coming down King William Street. Many parts of the extended jubilee celebrations were filmed, including the arrival of Victoria at a garden party at Buckingham House on 28 June, at which there were many distinguished guests including the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, and the papal envoy.

Victoria herself saw pictures of her own jubilee; a commemorative satin programme in the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum records a royal command film show given to Victoria and other members of the court in the Green Drawing Room at Windsor Castle on 23 November 1897 (Fig. 8). Like the earlier lantern shows or panorama visits, this too was part of a birthday celebration, in this case for Prince Henry of Battenberg. While the audience may have been elite, the different elements of the performance exemplify the intermedial aspect of most early film exhibitions. Victoria and the court saw fifteen different short films from Jolly’s Cinématographe, usually resident at the Empire Theatre of Varieties in Leicester Square. A number of the films projected were recorded by the Lumières; as well as the jubilee procession, there were actualities such as The Naval Review and Hussars Passing through Dublin, a comedy film The Joke on the Gardener, and the famed Serpentine and Butterfly Dances. Musical selections accompanied and enlivened the short films thanks to the Empire Orchestra, with the whole evening being introduced by an overture. Completing the variety programme was Monsieur Taffary’s Calculating and Performing Dogs (Barnes, II, 130–32). In her journal Victoria noted that ‘we saw Cinematograph representing parts of my Jubilee Procession, & various other things. They are very wonderful, but I thought them a little hazy & rather too rapid in their movements’ (QVJ, 23 November 1897).

At the time of the Diamond Jubilee, projected film was the great novelty, but it soon became a standard part of public royal occasions. Thus, audiences could watch Victoria arriving for the occasion of the laying of the foundation stone for part of the newly renamed Victoria and Albert Museum, or see her reviewing the Life Guards at Spital Barracks, Windsor on 11 November 1899 on their way to the Boer War in South Africa. (If you look at the ladies in the foreground on the left-hand side, you will see one of them taking photos.) It is often frustrating, however, that you cannot get a good view of Victoria in early film shorts. This is partly due to the protocols of the time and partly to the limitations of camera technology: she is often too far away or concealed by floral tributes! In trying to locate the Queen at these events it helps to know your regalia, so mugging up on the royal carriages in use at the time and uniforms of various military corps pays dividends. Her cream-coloured horses are very distinctive. Published details like the order of processions are also useful in identifying individuals and occasions and indicating the presence of the Queen. And even if there are few good views at least you get some of the scale and atmosphere of the events. You can intuit the colour and sound. (It is not necessary to add fake sound and false colour to appreciate these films.)

One fantastic new discovery is a view of the Queen in Dublin on her final visit to Ireland on 4 April 1900 (Fig. 9). It was filmed by W. K. L. Dickson for the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company with their large format camera (the film is 68 mm — so four times larger than the more usual 35 mm). For the first time, it gives us a close view of Victoria in motion (and smiling). The film is preserved at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and should be available to see with the other Victorian films at the BFI soon. This short clip of Victoria (seen here at 1min. 40s.) is the first time this film has been widely seen for 124 years.

By the time of Victoria’s death it was unthinkable that her funeral would not be filmed or that her chief mourners would not be aware of the cameras (Fig. 10). Films of every part of Victoria’s funeral procession received showings as far distant as New York, Bombay, Cape Town, Paris, Auckland, and Singapore. Global audiences were able to follow every stage of the event. Thus, this film shows ships firing a salute as Queen Victoria’s yacht, HMY Alberta, carries her bier from Cowes to Gosport before going on to London, while this film records the next stage of the funeral, showing the procession of the Queen’s coffin through the street from Victoria to Paddington. Lord Roberts is seen, as well as Edward VII and the Kaiser with the Duke of Connaught.19 There was an impetus to have the pictures developed and distributed as quickly as possible. In Melbourne funeral scenes were first shown at the local Athenaeum on 18 March 1901. They were also projected in Sydney at the Centenary Hall by 23 March 1901 and were exhibiting in Brisbane in early April.20

Conclusion

The fashioning of Victoria through different forms of moving and projected pictures certainly did not end with her death and funeral. The lantern would remain at the height of its educational and civic usage until at least World War I, and presentations of royal events and biographies remained a staple of lantern lectures as well as of stereograph sets. There were also dedicated film biopics such as Sixty Years a Queen (1913), Victoria the Great (1937), and Sixty Glorious Years (1938). Early film continued its fascination with monarchy through the filming of ceremonial events such as the Delhi Durbars of 1903 and 1911. With the twentieth-century pre-eminence of cinema, radio, and television, the patterns and formats established around Queen Victoria continued for subsequent monarchs (Fig. 11). While the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953 is often lauded as a landmark event in BBC broadcasting, royal events continued to be replayed by three-dimensional Viewmaster reels, movable children’s panoramas, and toy film strips, as well as numerous varieties of pull-out or telescopic peep shows.

Notes

- See Richard D. Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1978). [^]

- ‘Astley’s’, Morning Advertiser, 14 July 1838, p. 2; ‘Davidge’s Royal Surrey Theatre’, Morning Advertiser, 25 July 1838, p. 2; and ‘Exhibitions’, Court Gazette and Fashionable Guide, 15 September 1838, p. 13. [^]

- On the evolution of the moving panorama, see Erkki Huhtamo, Illusions in Motion: Media Archaeology of the Moving Panorama and Related Spectacles (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013). [^]

- On the growth and usages of the lantern, see Jeremy Brooker, The Temple of Minerva: Magic and the Magic Lantern at the Royal Polytechnic Institution, London, 1837–1901 (London: Magic Lantern Society, 2013); Realms of Light: Uses and Perceptions of the Magic Lantern from the 17th to the 21st Century, ed. by Richard Crangle, Ine Van Dooren, and Mervyn Heard (London: Magic Lantern Society, 2005); and The Magic Lantern at Work: Witnessing, Persuading, Experiencing and Connecting, ed. by Martyn Jolly and Elisa deCourcy (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020). See also, The International Lantern, ed. by Joe Kember (= Early Popular Visual Culture, 17 (2019)), pp. 1–133, 227–414, which contains numerous papers on global exhibition and usage of lanterns, including Australia, New Zealand, Belgium, Russia, and France. [^]

- On the coverage of the Diamond Jubilee and funeral, see John Barnes, The Beginnings of the Cinema in England 1894–1901, 5 vols (Exeter: Exeter University Press, 1996), III and V; and Ian Christie, ‘“A very wonderful process”: Queen Victoria, Photography and Film at the Fin de Siécle’, in The British Monarchy on Screen, ed. by Mandy Merck (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), pp. 23–46 <https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526113047.00008>. [^]

- See Edward Owens, The Family Firm: Monarchy, Mass Media and the British Public, 1932–53 (London: University of London Press, 2019). [^]

- ‘Great Rooms, Spring Gardens’, Morning Advertiser, 25 March 1823, p. 1. [^]

- See ‘Last Week of the Splendid Panorama’, Leeds Times, 19 March 1842, p. 5; and ‘Panorama of the Coronation’, Dublin Monitor, 13 November 1838, p. 4. [^]

- ‘Now Open — Diorama’, Morning Herald, 15 August 1839, p. 1. [^]

- Spooner’s Protean Views include one entitled ‘The Royal Rose of England’, in which a pink rose transforms to a portrait of Victoria when held up to the light. University of Exeter, Bill Douglas Cinema Archive, BDC70912. [^]

- See John Plunkett, Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); and Anne M. Lyden, A Royal Passion: Queen Victoria and Photography (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014). [^]

- Queen Victoria’s Journals (QVJ), 3 January 1833 <http://www.queenvictoriasjournals.org/home.do> [accessed 21 November 2021]. [^]

- QVJ, 14 April 1849. Other popular moving panoramas visited by Victoria and Albert (sometimes with children) include further visits to see moving panoramas of the Overland Mail (20 May 1850), Greive’s panorama of the principal campaigns of the Duke of Wellington, Albert Smith’s ascent of Mont Blanc (28 June 1852, 28 June 1854), and panoramas of Sebastopol and Alma (26 June 1855, 18 February 1856). [^]

- See Phillip Roberts, ‘Philip Carpenter and the Convergence of Science and Entertainment in the Early-Nineteenth Century Instrument Trade’, Science Museum Group Journal, 7 (2017) <http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170707>. [^]

- ‘The Queen’s Birthday’, Macleay Argus, 30 May 1894, p. 6. In Coleraine in the state of Victoria, to mark the Diamond Jubilee, the council arranged for the children in the town to be given a lantern lecture illustrative of Victoria’s life. See ‘Coleraine’, Mercury (Hobart), 27 May 1897, p. 4. [^]

- ‘Diamond Jubilee Lecture’, Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, 26 June 1897, p. 4. Other examples include, ‘Victoria’s Glorious Reign’, Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald and General Advertiser, 29 November 1898, p. 5. [^]

- ‘The Prince’s Derby’, Strand Magazine, August 1896, pp. 134–40 (p. 140). [^]

- On the precise position of the different cameras, see Luke McKernan, ‘The Other Diamond Jubilee’, The Bioscope <https://thebioscope.net/2012/06/16/the-other-diamond-jubilee/> [accessed 21 November 2021]. [^]

- See ‘Athenaeum Hall’, Melbourne Argus, 16 March 1901, p. 16; ‘Huber’s Museum’, New York Times, 16 March 1901, p. 19; ‘Royal Biograph’, Cape Times, 6 April 1901, p. 6; ‘Place aux Dames’, Graphic, 6 February 1901, p. 16; ‘The Cinematograph’, Times of India, 5 August 1901, p. 3; ‘The New Biograph’, Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, 10 July 1901, p. 2; and ‘Cinematograph Entertainment’, Auckland Star, 4 April 1901, p. 2. [^]

- See ‘Cinematograph Show’, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 April 1901, p. 9; ‘Athenaeum Hall’, Melbourne Argus, 18 March 1901, p. 3; ‘The Cinematograph Pictures’, Brisbane Courier, 5 April 1901, p. 6; and ‘Queen Victoria’s Funeral’, Australian Star, 23 March 1901, p. 4. [^]