The contributors to this Gallery section were given a simple brief by the journal editors.1 We were invited to write a short piece focused on just one object or text which might, in addition, respond to some aspect of Hilary Fraser’s work. It is an attractive task but, as I considered the many artworks and texts Fraser’s work has illuminated for me, I kept ending up back in the gallery itself, led there in part at least, it seemed, by one of Fraser’s own gallery experiences.

Delivering a striking paper on sculpture as mourning medium in 2015, Fraser began with a memory of visiting the Royal Academy in London to see a major Rodin exhibition (2006–07). It was an early venturing out following a period of bereavement and, by the time she reached The Burghers of Calais she needed to leave, overwhelmed by emotion that belonged to her but that she also somehow encountered, with surprise, as she moved through the Royal Academy’s rooms. In the article which developed from this paper, Fraser’s methodology for exploring the affective power of fin-de-siècle sculpture is avowedly shaped and bestowed by late Victorian thinkers.2 Among the most important is Vernon Lee, a writer with whom Fraser has long and fruitfully engaged.

This trigger is perhaps not so surprising as I have been working for a long time on Vernon Lee’s ‘psychological aesthetics’ where what happens in the gallery is of great importance to the experience of art. This strand of Lee’s work is theoretical but also experimental: it focuses on a body-mind situated in gallery (or museum or church or natural) space, looking, of course, but also moving: breathing, balancing, walking (eyes also move). Lee famously kept ‘Gallery Diaries’ where she recorded the mundane daily details of her energy levels, the fatigue occasioned by a bumpy cycle ride to a gallery in summer heat, the qualities of the crowds around her, the state of her heartbeat and breath as she visited and revisited the artworks of Florence and Rome.3

Fraser’s article explores why a piece of art moves us. Vernon Lee became more and more intrigued with how we move the static art objects we contemplate in gallery space. Lines in art are dynamic: they move, according to Lee’s theory of ‘aesthetic empathy’, because we project our own movement into them (we ‘give away our motion’).4 For a while, she toyed with the proposition that a kind of ‘inner mimicry’ of the shapes of art (of a statue in striking pose, for instance) takes place. More and more, though, she understood movement to be about form itself — lines and planes and angles to which our human motor movements respond. Of the Subiaco Niobid (the Efebo di Subiaco in what is now the Museo Nazionale Romano) she writes, ‘it affects me absolutely topographically, and when the man turns the pivot I have a sense of the monstrous as if a mountain were to rotate.’ She continues: ‘The “movement” we talk of is a pure movement of lines, either of lines rising, expanding, carrying, etc., when we stand fixed before them, or of lines changing when we walk round […] them’ (Beauty & Ugliness, pp. 254, 258, emphasis in original).

Lee’s conviction that art moves us because we are moving creatures can encourage experimenting of our own.5 Such experimenting can be of the simplest type but still strangely profound (‘moving’) as I found on a recent visit to Tate Britain’s major Walter Sickert retrospective held in 2022.6 This was the second time I have seen a Sickert show: the first was in the early 1990s shortly after I moved to London and began to look at art consistently for the first time. Among the first big shows I visited was ‘Walter Sickert, R. A., Paintings’ at the Royal Academy (1992–93). I disliked the paintings intensely: their muddy, gloomy colours made me feel claustrophobic. I hated the colour palette — the greens and browns especially — and the way the paintings resist access to the interior spaces they depict.

Visiting the 2022 show I was simultaneously entranced and shocked by how my response had changed and how much I liked these paintings. Sickert was a kind of sponge, soaking in from others what could happen with brush, paint, and canvas, but he was no copyist: the sense overall is of immense originality and achievement. I like especially his music-hall pictures: of performers (Minnie Cunningham at the Old Bedford (1892) or The Sisters Lloyd (c. 1889)) but mostly of audience. Sickert painted audience watching performers and we look at both. We move through gallery space seeing theatrical space and setting: crowded, craning bodies adapting to the architecture of stall and gallery, watching, talking, smoking, admiring. Performers gesture, sing, pirouette and the audience is no less active. Even seated, eyes flicker and stare, breath comes and goes (Gallery at the Old Bedford (c. 1894–95)).

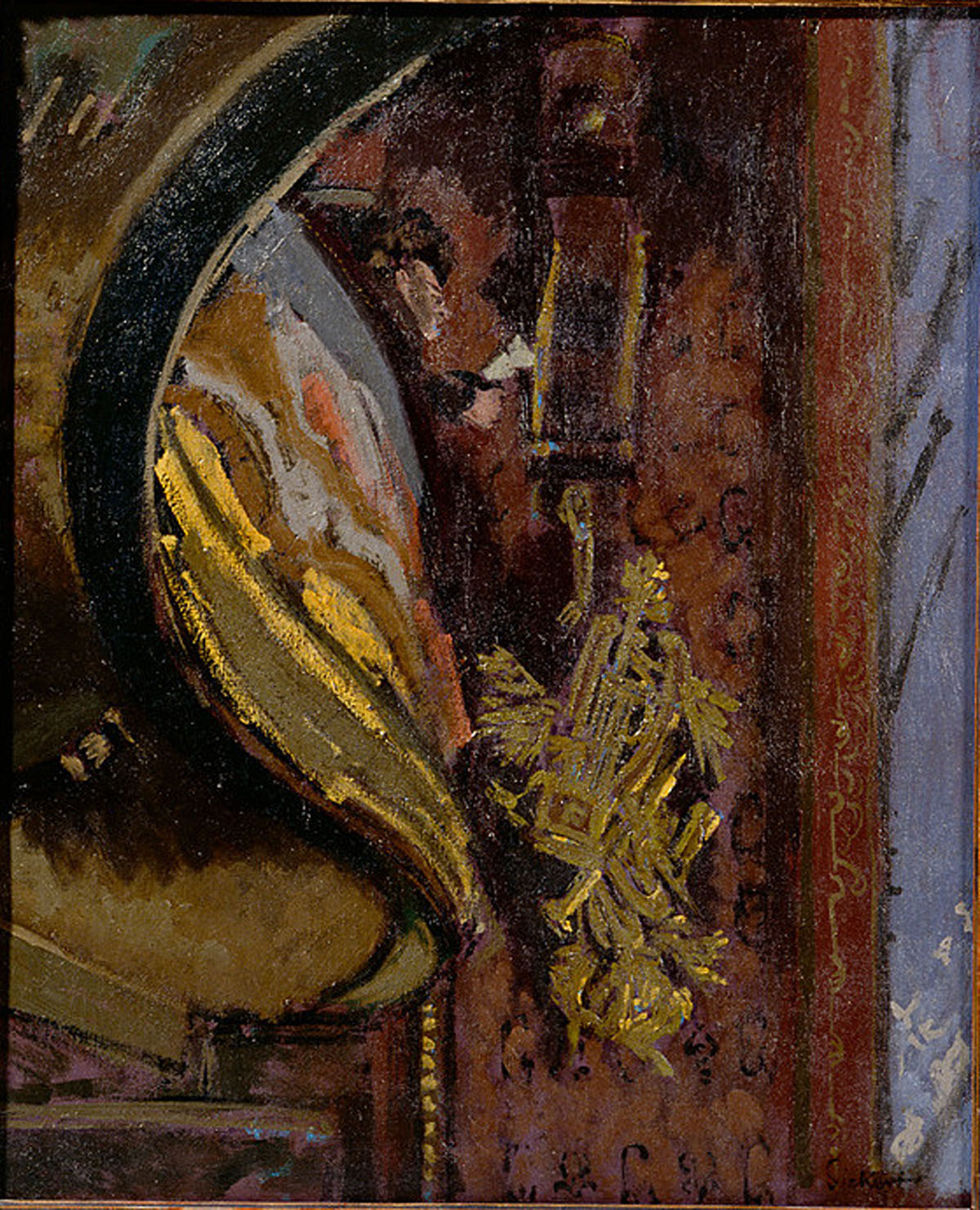

But how much, I wonder, do I owe to Vernon Lee for my response to a painting like Gaieté Montparnasse, dernière galerie de gauche (1906) (Fig. 1)? Why did this image arrest me so (and move me) with a similar sense of volatility and life when its one visible audience member is still, frozen in a moment’s attention fixed on the stage? Or perhaps they are scrutinizing the programme which is held aloft, almost at eye height, in hands that in turn are supported by arms propped on the balcony rail.

The dynamism of this picture comes from its — static, paint-and-canvas — depiction of (also static) theatre architecture. The left side of the canvas is dominated by a great sweep, or swoosh of the gallery balcony, viewed from low down, almost below the gallery itself.7 It slightly agitates me (is it as if it might collapse?). The right side of the canvas is dominated by verticals, holding in place the architecture of the stage. Visually, I clutch the right side to stabilize after following the upwards (but also horizontal) line of the balcony. It isn’t a feeling that the balcony will collapse, I realize, but that the swoosh makes me feel very slightly giddy and nauseous as I might on a fairground ride, with the same unsettled excitement.

Of course, other elements of the painting have effects too. The contrast between the dark underside of the balcony and its decorated face, the thickly lain paint of the latter and how its colours pick up the colour of the heraldic decoration on the proscenium arch, the dark-dressed figure and the dark balcony underside: all matter. But it is the painting’s movement of lines that moves me, and makes me uncertain, looking again, about whether the single spectator really is still: might they be leaning forwards, muscles supporting motion, to see down onto the stage, making the most of the restricted sightlines that their far-left seating permits?

Sickert through Vernon Lee is also a wider reminder of how important the sense of movement became for modernist aesthetics across the period Sickert is painting and Lee writing.8 Against what were often terrifyingly reductive forms of materialism at the turn of the century, the body and its movement were counter-conscripted to expansion, creativity, and resilience: V. E. Meyerhold’s ‘biomechanics’ and Rudolf von Laban’s ‘efforts’ revolutionizing movement in theatre; Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s eurhythmics in musical education; the extraordinary innovations of dance evidenced by the Ballets Russes, Loïe Fuller, Nijinska’s Les Noces; or the body techniques associated with figures like Joseph Pilates and much more.9 Movement pulls against the dividing of mind and body, reason and emotion: it plays a part in what art means.

Notes

- Thanks to Rob Swain for talking to me about theatre architecture and to Vicky Mills for sharing her response to Sickert’s painting. [^]

- Hilary Fraser, ‘Grief Encounter: The Language of Mourning in Fin-de-Siècle Sculpture’, Word & Image, 34 (2018), 40–54. [^]

- ‘Aesthetic Responsiveness: Its Variations and Accompaniments: Extracts from Vernon Lee’s Gallery Diaries, 1901–4’, in Vernon Lee and C. Anstruther-Thomson, Beauty & Ugliness and Other Studies in Psychological Aesthetics (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1912), pp. 241–350. [^]

- Vernon Lee, ‘Introduction’, in C. Anstruther-Thomson, Art and Man: Essays and Fragments (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1924), pp. 3–112 (p. 77), emphasis in original. [^]

- Carolyn Burdett and Rob Swain, Experimenting in the Galleries: Working with Vernon Lee: A Collaborative Performance Project <https://experimentingwithvernonlee.com/> [accessed 15 December 2022]. [^]

- ‘Walter Sickert’, Tate Britain, 28 April–18 September 2022 <https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/walter-sickert> [accessed 15 December 2022]. [^]

- It requires more expertise than I possess to be exact about what we see of the theatrical space. The painting may depict what in British theatres would be the dress circle: the final seat (or box) of the circle on the left of the auditorium. [^]

- For a wider history, see Roger Smith, The Sense of Movement: An Intellectual History (London: Process Press, 2019). [^]

- Or ‘the fine art of Jujutsu’, a version of which was taught by Emily Diana (‘Mrs Roger’) Watts to Vernon Lee’s collaborator, ‘Kit’ Anstruther-Thomson. See Beauty & Ugliness, p. 221; and Mrs Roger Watts, The Fine Art of Jujutsu (London: Heinemann, 1906). [^]