Ten months after Lady Wallace’s death in February 1897, the Hertford House Visitors’ Book was closed for the final time. For the previous twenty-three years, this large, black, leather-bound volume had been displayed on one of the desks in the Great Gallery, for visitors to sign as part of their tour of the collection. The book begins in 1876, shortly after Sir Richard Wallace had inherited Hertford House and refurbished it as a fitting home for his magnificent art collection, and continues until December 1897, after Lady Wallace’s bequest of the collection to the nation. During this period, Hertford House was a private collection that could be visited by prior appointment or on occasional open days. After 1897 the Visitors’ Book became part of Lady Wallace’s legacy to Sir John Murray Scott, who had been private secretary to both Lady Wallace and Sir Richard. It remained in his family’s possession until the death of his sister Mary in 1943, at which point it returned to its original home at Hertford House.1 Now one of the most important documents in the Wallace Collection Archive, it has recently been digitized and is available to view on the Internet Archive (Fig. 1).

From 2017 to 2018, I transcribed the 245 pages of the Visitors’ Book, deciphering the identities of the signatories. Only a handful of visitors had left comments alongside their signatures and so a mere list of names was the starting point for all the research that followed. The signatures took me on a whistle-stop tour of British, European, and American society of the late nineteenth century — and of all types of handwriting, from neat to indecipherable. The visitors cover a number of different categories: royalty, nobility, military men, art critics, historians and collectors, artists, wealthy businessmen, and men of the cloth. The overwhelming category here, of course, is men, many of whom are of great interest. Disraeli famously visited, as did Auguste Rodin, Thomas Hardy, Louis Comfort Tiffany, and many other renowned and/or wealthy men.

However, the variety of female visitors to the Wallace Collection deserves special attention, for although they are less well known than their male counterparts, their lives and stories possess no less interest for understanding the nineteenth-century public’s engagement with art. Unfortunately, it is far more difficult to identify the female visitors to Hertford House, as they often signed the book under their husband’s name and tended to disappear into the shadow of his usually better-documented life.

For a long time, Lady Wallace herself has been subject to a similar kind of erasure. Although the name most connected with the collection is that of Sir Richard Wallace, it was his wife who actually left the collection to the nation and ensured its survival to the present day.2 It was also she who determined that the name of the new museum should be ‘The Wallace Collection’. Without her influence, the museum might look very different today. As so much of her life is undocumented (not a single piece of writing in her own hand survives), one might assume that, in founding the museum, Lady Wallace acted under the influence of Sir Richard Wallace and John Murray Scott, but that seems too simplistic; she must be allowed her own agency, will, and vision. Although she most probably discussed the matter with her husband and with Murray Scott, she was the one who took decisive action when she need not have done; indeed, she could have sold the complete collection after her husband’s death. Instead, she gifted almost the entirety of the collection to the nation, enabling it to be enjoyed and admired to this day.3

Although men largely dominated public life in the nineteenth century, women were occasionally, if favoured by fortune and education, able to step beyond the private and domestic sphere to which they have been considered to be tethered. Many if not most of the women discussed in this article can be seen to emerge into public life to a greater or lesser extent. They enter, variously, the worlds of medicine, social work, scholarship, or art, in ways reminiscent of Kathryn Gleadle’s description of upper- and middle-class women entering into politics in the nineteenth century.4 Stepping beyond the private sphere was easier for women if the private could be merged with the public until it became private enough for women to have a stake in it.5 Museums, and especially private collections, straddled this public/private divide, especially if they were contained in private houses that were also open to a limited public, including women. In the nineteenth century the added possibility of self-improvement and education through the viewing of the art on display would have reinforced the propriety of such visits for women. In Molly Hughes’s charming autobiography, A London Child of the 1870s (1934), she describes museum visits as forming part of her homeschooled education:

A picture gallery was often a reason for our going into the West End. The Turner room at the National was as familiar to me as the dining-room at home, and mother early taught me to regard these pictures as my own property. ‘Given to the nation,’ she would roll on her tongue as she feasted her eyes on the Fighting Téméraire. Then there were the Dudley and the Grosvenor galleries, wherein enthusiasts were few. Around the solemnly quiet rooms I would march with a catalogue, ticking those I liked, and condemning those that seemed feeble.6

The Hughes family were middle class but money was scarce and so these museum visits were a treat; they show how essential Molly’s mother considered her appreciation of art to be. The public museum was still a relatively new type of institution in the 1870s and the proprietary way in which Molly and her mother viewed the art at the National Gallery shows that these new public spaces were valued and in no way taken for granted. This quotation also reveals much more to the reader than the plain lists of names in most visitors’ books of the time: a reaction to the artworks viewed.

Visitors’ books such as the one at Hertford House were common in the nineteenth century and were maintained by all sorts of establishments, from private houses to hotels. Recent scholarship has rediscovered these books as sources of information regarding Victorian travel, hospitality, and interests.7 Many such visitors’ books contain simple lists of names, whereas others resemble autograph books, with longer comments and even sketches. With its few comments, the Wallaces’ book is very much in the former category but nevertheless hints at the enduring fascination that the collection held for large numbers of people from all manner of interest groups from doctors to artists, and from colonial governors to neighbours from Manchester Square.8

Among the female signatories of the Visitors’ Book at Hertford House, several potential case studies are of interest: members of royal families, doctors, artists, art collectors, social reformers, and intellectuals, all united by their interest in Sir Richard’s famous art collection. Almost all of them were significant in widening the scope for women’s participation in public life, much as Lady Wallace had done by being a female founder of a museum. Nevertheless, most of the women discussed had one material advantage: they were from relatively or extremely wealthy families. Their families’ money and influence enabled them to push or redefine the boundaries of the private sphere and to infiltrate public life in ways that were impossible for their poorer contemporaries.

This article covers twenty-four women (some well known, others largely forgotten) grouped into nine loosely defined categories — royalty, doctors and nurses, women’s rights activists, social reformers, society ladies, entertainers, artists/designers, art collectors, and intellectuals — conceptualizing the types of women engaged in art visiting in the later decades of the nineteenth century. The pieces of art in the collection have a deeper historical significance than their decorative value, as do the stories that hide behind the women’s names and that recount the possibilities open to a determined (and fortunate) woman in the nineteenth century.

Royalty

Many of those who visited Sir Richard’s collection were members of the royal families of Europe and beyond. Indeed, the very first visitor recorded on the opening page of the book is Augusta, Empress of Germany. Other notable royal visitors include most of Queen Victoria’s children, Emperor Pedro II of Brazil (June 1877), and Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria (25 June 1897).

One of the best-known visitors was Victoria, ‘Crown Princess of Germany and Prussia and Princess Royal of Great Britain and Ireland’, as she most helpfully signed herself. She was the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria and later became Empress Frederick of Germany and Prussia. She visited the collection six times between 1878 and 1897 with various members of her entourage. On her last visit she signed the book as Dowager Empress, as Frederick III had died in 1888 after only ninety-nine days on the throne.

Victoria (1840–1901) was a great lover of art and had been taught by the best teachers as a child. In adulthood she sculpted and painted in oils, and also collected art. As the daughter of art-loving and wealthy royal parents, she received an excellent and extensive education. She later showed herself to be a proponent of women’s education, setting up schools for girls and nursing schools in Germany and engaging in a wide variety of charitable works. The limitations placed upon her were not those of a lack of wealth or opportunity but rather of the strictures of life at a conservative royal court in a country where she was always regarded with more suspicion than affection.9

The princess would presumably have first heard of Sir Richard’s collection when her brother, the Prince of Wales, attended the opening of Sir Richard’s Bethnal Green exhibition in 1872, or possibly even before, as her mother had visited the collection in 1871, six months after Lord Hertford’s death and Sir Richard’s inheritance (Higgott, ‘Most Fortunate Man’, pp. 132, 282). Victoria’s mother-in-law, the Empress Augusta, might have told her about it too. Documentary evidence shows that the princess was definitely aware of Sir Richard’s art collection by 1877, as stated in a letter to her mother on 7 April regarding the visit of a member of her court, Count Seckendorff, a keen amateur artist, to England: ‘Count von Seckendorff also leaves for London for the purpose of making a copy or two in the National Gallery — or by permission of Sir R. Wallace, in his gallery.’10 Although no evidence for the survival of these sketches can be found, two watercolours and an oil copy of a Winterhalter portrait of Arthur, Duke of Connaught, preserved in the Royal Collection, show that Seckendorff had some skill as a watercolourist and was an able copyist.11 The Visitors’ Book records the count’s visit on 14 April 1877.

Sir Richard’s collection obviously impressed Princess Victoria. In a letter to her mother after his death, she remarked upon his ‘matchless Collections in London which I know so well and admire so much’.12 In a catalogue dated 1896 from the Dowager Empress’s own collection at Schloss Friedrichshof, Wilhelm Bode describes the arrangement of the artworks in the rooms of the then modern palace as being influenced in style by the Marquess of Hertford (and therefore also Richard Wallace), Adolphe Rothschild, and other members of the Rothschild family. The types of item that she collected greatly resemble those found in Sir Richard’s collection and she presumably was inspired by the way in which he had displayed them: not in a coldly scientific way, as could be found in many museums, nor as a jumble of interesting objects arranged unsympathetically, but instead in such a way that each object complemented the others in age or style without overwhelming the viewer.13

Victoria maintained her interest in Sir Richard’s collection until the end of her life. In 1898 she recommended a visit to her daughter Sophie: ‘I forgot to say before you went that I wish you could manage to see Sir Richard Wallace’s collection which he left as a museum for the nation’ (Empress Frederick, ed. by Lee, p. 279). At this point, the collection was in a state of flux, already left to the nation by Lady Wallace — although she is not acknowledged here — but not yet opened as a public museum. As the Visitors’ Book ends in December 1897, it is unfortunately impossible to say whether Sophie took her mother’s advice.

Doctors and nurses

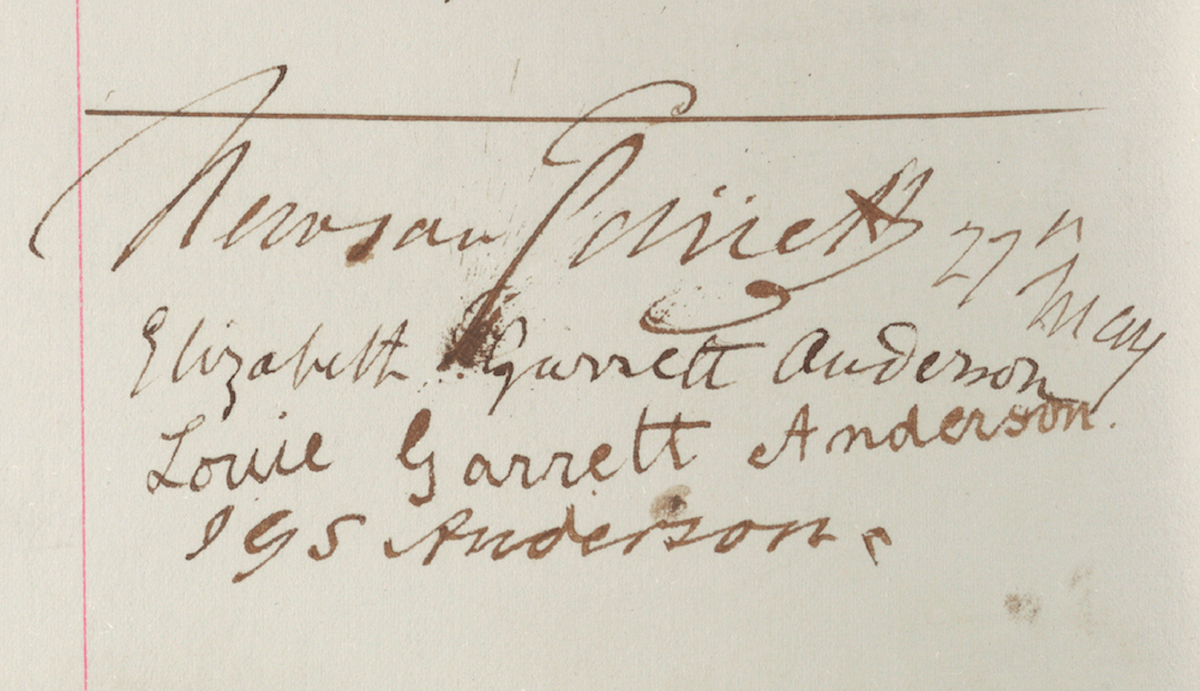

As wives of royalty or men of influence, women wielded a certain amount of authority but rarely in their own right or in a professional capacity. However, in the late nineteenth century, women were slowly breaking into the medical profession, against much male opposition. Two female medical pioneers, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and her daughter Louisa, accompanied by Elizabeth’s father and husband, visited the collection in May 1883. Both fought hard for their advancement into academia, medicine, and even military medicine. Most women could never have afforded the expensive education necessary. All the women who paved the way for later female medical students needed both private means and family support to enable them to gain the education necessary, especially as they often had to take medical examinations abroad (Fig. 2).14

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836–1917) was the first female qualified doctor (and the first female town mayor) in England. Her road to becoming fully qualified was a long one as no medical school would accept her as a student; at that time, medical degrees were reserved for men. She finally managed to qualify in 1865 after first becoming a nurse and then using the examinations of the Society of Apothecaries as a back door into the profession. Five years later she received a medical degree in France, having taught herself French for this purpose. The fact that she continued in the medical profession that she had fought so hard to enter, in spite of marrying and having three children, is testament to her determination and spirit. Her interests seem to have been largely focused on medicine and the fight for women’s rights to education and the vote, but artistic interests can be seen within the Garrett family: Elizabeth’s sister Agnes and cousin Rhoda were interior designers who published a book on the subject of Queen Anne style.15

By the time that Louisa Garrett Anderson (1873–1943), Elizabeth’s daughter, became a physician and surgeon, women were allowed to receive medical degrees in England like their male counterparts; she first attended Bedford College for Women and then the London School of Medicine for Women. After qualifying, Louisa worked at various London hospitals, travelled to the United States to gain more experience, and founded a hospital for children. In working with women or children who would otherwise have had little or no access to medical care, female doctors fulfilled their more traditional caring and charitable roles while also broadening the sphere in which women could work. The expansion of women’s medical work into other areas came about partly through the First World War. Louisa is a good example of this development, becoming chief surgeon to three hospitals. With her partner Flora Murray, also a physician, she founded the Women’s Hospital Corps just six weeks after the outbreak of war in July 1914 and they offered their combined services to the French Red Cross. Shortly afterwards, she wrote to her mother:

I wish the whole organisation for the care of the wounded — their transport, the disposition of base and field hospitals and their clothing and feeding cd be put into the hands of women. This is not military work. It is merely a matter of organisation, common sense, attention to detail and determination to avoid unnecessary suffering and loss of life. Medical women could do it so much better than it is done — especially if the right med. women were chosen for the job — ahem!!16

Their first hospital was in the under-equipped shell of Claridge’s Hotel in Paris, their second was closer to the front in Wimereux, and their third, officially endorsed by the War Office and funded by the army, was Endell Street Military Hospital in Covent Garden, which was run and staffed entirely by women from 1915 to 1919 (Fig. 3). Around twenty-six thousand patients were treated at Endell Street, with over seven thousand major operations being performed during that time. Both Louisa and Flora received CBEs for their war work.17 Although the Women’s Hospital Corps was disbanded in 1919, its members opened up the way for women in all aspects of medicine by proving beyond doubt their competence, their administrative skills, and their dedication to that toughest of audiences, the male establishment in the form of the British Army.

Another visitor to the collection with a medical and army connection is Elizabeth Harris (1834–1917), who signed the Visitors’ Book as Mrs Webber Harris in May 1883. She was the wife of a British Army officer in India and her nursing activities appear to have been carried out without any formal training. In 1869, when an outbreak of cholera struck, her husband’s unit was given orders to attempt to march out of range of the disease, with Mrs Harris being the only woman to accompany them. She nursed the sick soldiers and saved many lives. The regiment so appreciated her bravery and care that they asked and received permission from Queen Victoria to have cast a copy of the Victoria Cross in gold, which was presented to Mrs Harris and remained one of her most treasured possessions for the rest of her life (Fig. 4).18 Mrs Harris’s actions may have made her a more traditional Florence Nightingale-esque Victorian heroine than the women discussed above but she is nevertheless unique in that she is the only woman to whom a Victoria Cross, however unofficial, has ever been awarded. The medal, together with a portrait medallion, can now be admired in Lord Ashcroft’s gallery at the Imperial War Museum.

Women’s rights activists

Many of the female pioneers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were interconnected and active in more than one field. Both Garrett Andersons were associated with the fight for women’s right to vote: Louisa became a suffragette and persuaded her mother to join the cause. The two women were part of a deputation to the prime minister to propound the case for women’s suffrage in 1910. Louisa even went to prison for activities as a suffragette. In a letter to her mother she described women working in military medicine as ‘suffrage work — or women’s work — in another form’.19

Of all those women who would later become suffragists or suffragettes, however, Constance Lytton (1869–1923) is perhaps the best-known activist to have visited Sir Richard’s collection. As a young woman she came to Hertford House in March 1897 with her mother, sister, and her sister’s future husband, the architect Edwin Landseer Lutyens. Although Constance’s early life was that of a standard Victorian lady of means, she would later become part of the Women’s Social and Political Union, founded by the Pankhursts. As the Garrett Andersons were members of the WSPU at the same time, they probably all knew each other. Constance became a radical suffragette who went to prison and endured hunger strikes and forced feeding. In an interesting twist on the way that rank and wealth aided many of the other women discussed in this survey, Constance felt constrained by them. At first her connections led to her preferential treatment by the police, and so she decided to conceal her true identity, taking the name of ‘Miss Jane Wharton’ in order to be on an equal footing with other suffragettes who were not so privileged. She paid a heavy price for her activism as her already weak health gave way and she suffered both a heart attack and a stroke as a result of her ill treatment. She remained an invalid for the rest of her relatively short life but lived to see women get the vote in 1918.20

The connection that most would make between suffragettes and art is that of suffragettes slashing paintings with meat cleavers but less well known is that many of them were artists themselves, frustrated by years of fighting the male establishment for recognition. Indeed, a number of suffragettes were involved in the Arts and Crafts Movement, with suffragette artists designing the striking banners and posters that are still so familiar to modern audiences.21

Social reformers

One of the ways in which women were becoming more involved in public life in the nineteenth century was through the beginnings of a more defined system of social work. Women had long been involved in charitable works, especially with children and the poor. This type of philanthropy was considered the natural domain of women as the nurturers of society and was widely regarded as an extension of the caring shown for children and other dependants in the home.

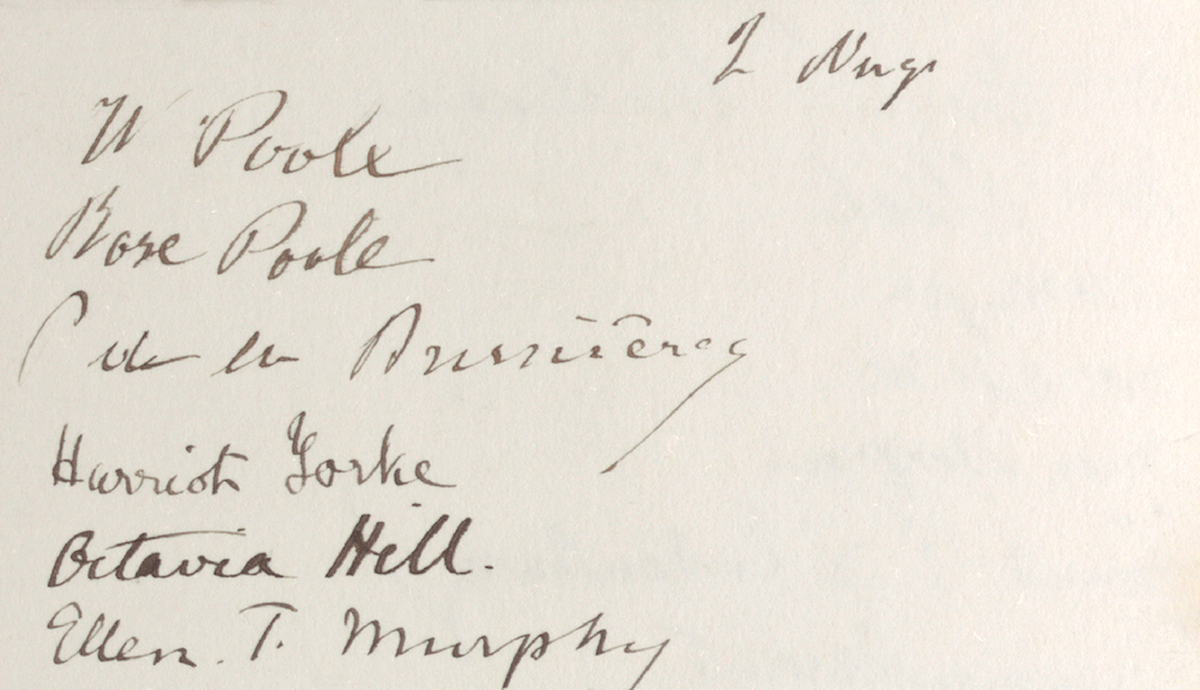

One of the first women known for more organized social work in England was Octavia Hill (1838–1912). She visited the art collection at Hertford House in August 1893, accompanied by her companion and fellow worker Harriet Yorke (Fig. 5). Octavia had an unconventional upbringing for the time, her mother being a strong advocate of women’s education. Although her family were by no means wealthy themselves, she observed the sheer poverty and lack of self-respect of the utterly impoverished, especially in big cities, and was prompted to help the poor to help themselves. In London she worked for the Ladies’ Guild, a cooperative crafts workshop, and then, through the sponsorship of F. D. Maurice, became secretary to and later teacher at the women’s classes taking place at the Working Men’s College in Bloomsbury. During this time, she also came to know Ruskin and was trained by him as a copyist. In her younger years she visited daily the Dulwich Picture Gallery or the National Gallery in order to copy pictures, usually at Ruskin’s bequest. He thought highly of her artistic talents and employed her to copy a number of works, particularly Turners, for the final volume of his Modern Painters.22 In 1859 Octavia wrote to her sister Miranda:

I am particularly happy about my work. Ruskin is so pleased with it all. My four Dulwich drawings are now right and ready to use; in fact he wants them at once that they may be put into the hands of the engraver. I am to do four more, small, but, Ruskin says, difficult examples of inferior work — and one bit from Turner. (Life, ed. by Maurice, pp. 172–73, emphasis in original)

Although they later quarrelled, Ruskin also invested in her housing scheme, in which she took over and renovated run-down residential buildings to provide better homes for the poor. In many ways Octavia acted as a social worker to her tenants, regularly inspecting properties, giving advice, and trying to improve their lot in life. Several of her social housing projects, such as Barrett’s Court (now St Christopher’s Place) and Paradise Place (now Garbutt Place), were in Marylebone, in close proximity to Hertford House. Her interest in art and philanthropy were inextricably linked from the beginning of her working life at the Ladies’ Guild; art and beauty had a dual role to play, lifting the poor both economically and spiritually. This can be seen in the Red Cross cottages, hall (with inspirational murals), and gardens in Southwark, which she was instrumental in developing. The gardens also show Octavia’s interest in providing outside spaces for all to enjoy. To this end she prevented development on green spaces in cities and became one of the founders of the National Trust. However, although she wanted women to be able to be involved in politics on a local and domestic scale, she did not approve of them having the vote.23 During her visit to Hertford House, she would no doubt have admired paintings similar to those she used to copy elsewhere, particularly if she was fortunate enough to view the four Turner watercolours purchased by the 4th Marquess of Hertford.24

A similar pioneer of social work, but in Germany, was Selma, Gräfin von der Gröben (1856–1938), who came to Hertford House in May 1883 at the age of twenty-six, accompanied by her mother and sister. The family had ties with London as Selma’s mother had been born there as the daughter of the Hanoverian minister to George IV, and her uncle was ambassador to London at the time when she visited Sir Richard’s collection. From a titled family but not wealthy in her own right, Selma was involved in a wide range of social work, especially with female orphans, unmarried mothers, prisoners, and prostitutes. Such work, although generally regarded as praiseworthy, was also sometimes frowned upon, as it brought women into contact with those ‘undesirable’ parts of society that were supposed to be hidden from respectable women. All her efforts were focused on making disadvantaged or ‘fallen’ women useful members of society. In particular, the German Evangelical Women’s Society, of which Selma was a member and later its leader, had a three-pronged approach to tackling their work, focusing on women’s rights, religion, and social politics. As a basis for her work, Selma became a self-taught expert on the law as regards women and children in order to be better able to help them.25 Much like Octavia Hill in Britain, she began a move towards more organized social work and social reforms that would aid women and the poor.

Society ladies

Many of the women who came to visit Sir Richard’s collection were society ladies whose wealth allowed them more independence than was enjoyed by their poorer female contemporaries. One such freedom was the ability to travel. Sir Richard’s collection appears to have been popular with American visitors to London, a trend that continued even after his and Lady Wallace’s deaths as American newspapers eagerly reported the bequest and the opening of the museum.26 It is striking to see the signatures of so many Americans in the Visitors’ Book and to realize how many of these signatures belonged to women. Most American women visited Sir Richard’s collection as part of a tour of Europe, largely accompanied by relatives or paid companions as it would have been frowned upon, at that period, for a woman to travel alone.27

One such example of the freedom that wealth brought is Ellen Peabody Endicott (1833–1927). She was an American society hostess in Boston and Salem, Massachusetts and Washington DC. She visited the collection in July 1883 with her daughter Mary, later the wife of the British statesman Joseph Chamberlain and a noted member of London society, and with her husband William Crowninshield Endicott, who was an American judge and politician, serving as President Cleveland’s secretary of war in the late 1880s.28 As leading members of Boston society, she and her family were supporters of the Museum of Fine Arts, and she can be found on the list of subscribers in its annual reports from 1902, shortly after her husband’s death, until her own death in 1927. In 1915 in honour of the opening of the new Evans Wing of the museum, she even lent it two paintings: a landscape by William Morris Hunt and a John Singer Sargent portrait of her son William Jr, who would continue the family’s involvement with the Boston museums by becoming treasurer to the Museum of Fine Arts and trustee to the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum.29

A British society hostess of a similar time was Margaret Helen Greville (1863–1942), illegitimate daughter of Scottish brewing magnate William McEwan, with whom she visited the collection in July 1894. Despite her lack of pedigree, she married Ronald Greville, a Conservative politician and close friend of the Prince of Wales, later Edward VII (Fig. 6). Margaret was a good friend of Mary of Teck, later Queen Consort of George V, and enjoyed the finer things in life, holding many house parties at her art-filled country estate, Polesden Lacey in Surrey. Her father had been a keen art collector, particularly of Dutch paintings, and bequeathed his collection and his interest in collecting art to his daughter. She added to his collection of pictures, furniture, and other works of art and displayed them in the lavish surroundings of Polesden Lacey, which McEwan had also purchased for her. Instead of focusing on her art collection, society at the time joked, rather snobbishly, that she enjoyed collecting royalty. She certainly favoured the British royal family: on her death, she bequeathed her jewels to Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother, who had spent her honeymoon with the future George VI at Polesden Lacey. The jewels are still in the ownership of the royal family today; one of the diamond tiaras from the bequest was worn by Princess Eugenie at her wedding. Although she was certainly not philanthropic in a traditional sense (‘people leave their money to the poor, I intend to leave mine to the rich’),30 Margaret’s wish that her art collection might be appreciated by others can be seen in the fact that, on her death in 1942, she left her house, along with its collections, to the National Trust in memory of her father. She wanted ‘to form a Picture and Art Gallery in a suitable part or parts of the house’, that should be ‘open to the public at all times and […] enjoyed by the largest number of people’ (Chu, p. 3). She thus acted entirely in the pattern set by Lady Wallace.31

Entertainers

Not all visitors to the collection came from high society or were necessarily regarded as respectable. Actresses and dancers were on a delicate footing in society, especially when they were foreigners too, for whereas they were admired for their skill, they were also looked down upon for their morals, whether this was justified or not.32 They were more likely to become a wealthy man’s mistress than his wife, but two of the performers who visited the collection had made that jump into respectability.

Marie Taglioni (1804–1884) was a ballet dancer who at the height of her career had danced in London, Paris, and St Petersburg. She is rumoured to have been the first ballet dancer to dance en pointe. Marie married a French count but soon separated from him. Divorce followed and she brought up her two (possibly illegitimate) children alone. In spite of this she continued with her dancing career, helped to improve the ballet section of the Paris Opéra, and later taught children and society ladies dance and deportment in London, showing that she managed to retain her place in respectable society.33 She visited the collection in her old age, in August 1879, signing the Visitors’ Book as ‘veuve Ctesse Gilbert de Voisins, née Taglioni’.

Kate Terry Lewis (1844–1924) was an actress, better known by her stage name of Kate Terry. She signed the Visitors’ Book as Kate Lewis in May 1885, alongside her husband Arthur, a silk mercer with an appreciation for all things artistic. Kate is connected to many of the acting dynasties from the Victorian period onwards: her sister was Ellen Terry, famously portrayed as Lady Macbeth by John Singer Sargent in 1889, and she was the grandmother of actor Sir John Gielgud. Acting was still considered a barely respectable profession for women in Victorian times. However, this was slowly changing, and several famous actresses who had made a career on the stage later married into upper-class society. As actresses they were of course immersed in public life, both on the stage and at society events. Kate had been trained for the stage almost from birth, first appearing on stage aged four. She retired from her acting career on her marriage at the age of twenty-three, a sacrifice memorialized by her husband in the gift of a gold bangle with all of her theatrical roles inscribed inside it (now in the collections of the V&A).34 On her visit to Hertford House, Kate might have been fascinated by the three portraits of Mrs Mary Robinson, an actress of an earlier era, by Gainsborough, Reynolds, and Romney.

Music formed part of every well-educated girl’s education. However, only a few managed to become professional musicians. One female musician who defied such limitations was Alma Hollaender Haas (1847–1932), a German pianist and daughter of a musical family, who moved to London and married a professor of Sanskrit at University College London. Her musical career was put on hold when she had two children, but she soon took up her work as a concert pianist and teacher once more. She was particularly well known for her performances of Beethoven (much admired by George Bernard Shaw) and Schumann and her love of chamber music. Alma taught piano at Bedford College for Women and, most unusually for the time, became head of music at King’s College London in 1886. She was also briefly a professor at the Royal College of Music in 1887 but soon gave up that post in favour of her position at King’s. She taught some illustrious private pupils: in the 1920s these included children of the Spanish royal family. Alma was another trailblazer who was engaged in bringing more women into her line of work: she became president of the Society of Women Musicians in 1914. Always keen to support education, she donated her husband’s orientalist library to the recently founded School of Oriental Studies (now SOAS).35 She visited Sir Richard’s collection with her father and sister in May 1884.

Artists/designers

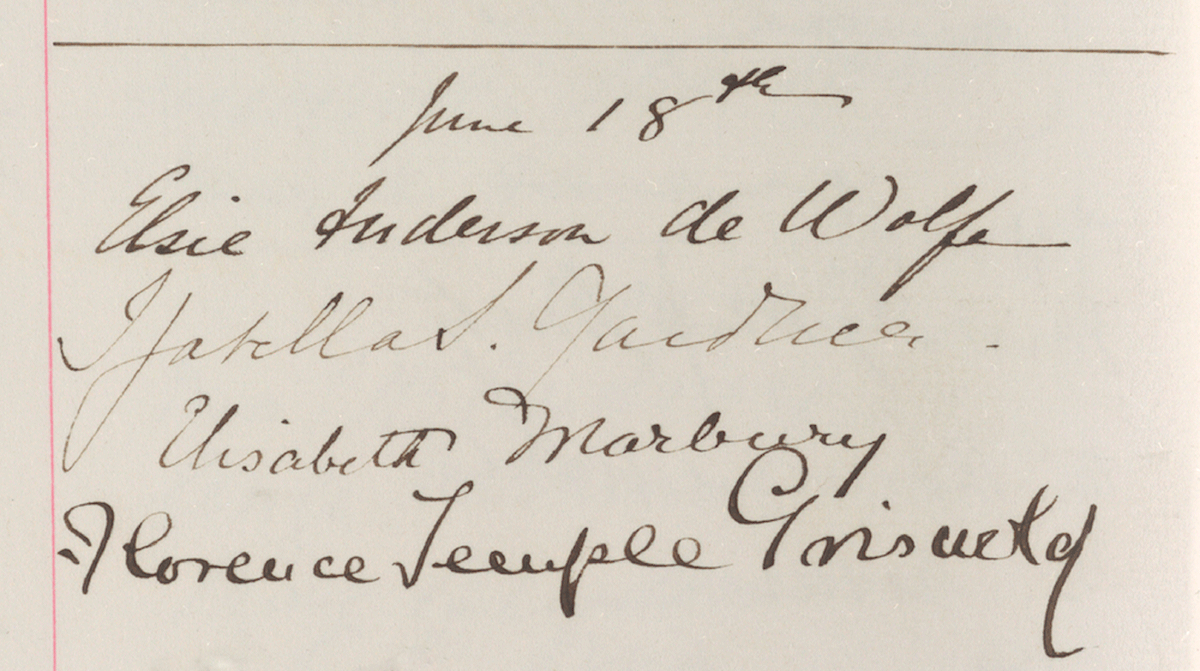

As might be expected, several of the women who visited the collection showed great artistic appreciation and abilities. American interior designer Elsie de Wolfe (c. 1859–1950) was one of these. She was first an actress (better known for her costumes than her talent) and later became interested in interior design, thereby inventing the profession of interior designer. Abhorring the heavy and often dark clutter of Victorian style, she sought to combine light and beauty with practicality for everyday life, using light colours, chintz fabrics, painted wood, and copious numbers of mirrors to create a sense of space and comfort. Her style was chiefly inspired by that of the French eighteenth century and was encouraged by summer visits to France, especially Versailles. She purchased antiques to ship back to the United States and consulted with Versailles curator Pierre de Nolhac regarding items to buy. Back home, she built up a reference library on the subject of French design. Her visit to Sir Richard’s collection, which predates her days as an interior designer, may have played a role in shaping her tastes. She visited twice in quick succession in June 1890, once with her constant companion Elizabeth ‘Bessie’ Marbury, one of the first female theatre agents and Broadway producers (Fig. 7). The combination of Bessie’s connections and Elsie’s design talents proved to be a winning one. Elsie later designed interiors for the rich and famous in the United States and England and was a well-known society figure in her own right in New York, London, and Paris. Her designs, then so innovative, now seem the norm, demonstrating her ability as a tastemaker for America and Europe.36

Women were often expected to be good amateur artists and, indeed, drawing and painting were considered a standard part of an upper-class girl’s education. Becoming a professional artist had always been more difficult for women but with new art schools opening, so also did doors to a hitherto nearly unreachable status beyond that of the keen amateur.37

Artists Ella (1858–1946) and Nelia Casella (1859–1950) were sisters who trained at the Slade School of Fine Art in the 1880s under Alphonse Legros, who himself visited the collection with the sculptor Auguste Rodin. The Slade was open to women from its beginnings in 1871 and, as it formed part of University College London, paved the way for women to be accepted at the university as a whole. The sisters are best known for designing medals and working in wax, although they also illustrated books. Several examples of their work are held at the Victoria and Albert Museum. They were part of an active theatrical and literary circle, which included Ellen Terry, and made many wax portraits of their friends, often in theatrical costume. The Renaissance waxes of Sir Richard’s collection must have interested them greatly, as they worked with the same medium and drew from the same tradition.38 They visited with their father in July 1897, after Lady Wallace’s bequest to the nation.

American artist Dora Wheeler (1856–1940), later known as Dora Wheeler Keith, came to the collection in June 1884. She was a New York artist celebrated for her portraits, although she additionally worked as an illustrator and designer of tapestries. She not only created art, but also donated a number of works to the Cleveland and Metropolitan museums of art (largely samples of textiles designed by her mother Candace Wheeler and her company Associated Artists).39 The donation and resulting preservation of these textiles demonstrate a love of this particular medium, which for much of its history was dominated by female workers. She visited the collection with a group of other American visitors who included John Taylor Johnston and his son-in-law Robert Weeks De Forest. Johnston was the founding president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Weeks De Forest was a later successor to that post. Her companions on her visit show that she was part of a wider social circle that was much involved with philanthropy and collecting art.

Art collectors

Men had the upper hand when it came to both their training as artists and their collecting of art. Women often had the disadvantage of having no income of their own or of being subsumed under their husband’s name, even when they were equally involved in the collecting of art. Unsurprisingly, many of the women discussed in this article were collectors, even if this was not always their main claim to fame. Three renowned female art collectors visited the collection and may have been inspired by Lady Wallace’s gift to the British nation to form museums in their own countries either before or after their deaths.

Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924) was a member of Boston high society and an avid art collector who travelled extensively with her husband to Europe, Egypt, and the Orient (Fig. 8). She had constructed, in Boston, a large house in the style of a Venetian palazzo, in which she arranged her collection.40 This house is now the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. She visited Sir Richard’s collection twice, once accompanied by Elsie de Wolfe in June 1890 (see Fig. 7), and once in July 1897 with a group including Bernard Berenson, the art dealer who advised her on many of her purchases. In many areas her tastes and collections mirror Sir Richard’s; for example, they both owned paintings by Titian, Rembrandt, and Rubens. Her last visit dates from the period after Lady Wallace’s bequest but before the official opening of the collection as a public museum. The bequest may have encouraged the idea of opening her own collection to the public in 1903. Sadly, her archive does not record her opinion of the collection displayed at Hertford House, but the fact that she visited twice, all the way from Boston, and despite all the other attractions in London, is significant.

Another American collector and museum founder who signed the Visitors’ Book was Eleanor Garnier Hewitt (1864–1924), a keen traveller and collector with an interest in education. With her sisters Sarah and Amy, she founded in New York the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration (inspired by the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris) in 1897. The collections featured an eclectic mixture of decorative and graphic arts. Like Elsie de Wolfe (a friend of Sarah’s), Eleanor and Sarah were also interested in the future of domestic taste. They sought to educate the wider public, but especially designers and craftsmen and women, by presenting good examples of past styles. The museum’s primary purpose was the practical education of art students studying at the Cooper Union, which had been established by the sisters’ grandfather Peter Cooper in 1859. The Cooper Union was a free educational establishment for all who wished to learn but was also open to the public with free entry three days a week.41 For women, this educational opportunity would have been particularly valuable because it offered the rare chance of a creative career. Eleanor visited Sir Richard’s collection with her sister Amy in July 1884.

Nélie Jacquemart André (1841–1912), who was a French artist and art collector in her own right, was married to fellow art collector Édouard André. They visited together on two consecutive days in July 1886. Much as was the case with Sir Richard and Lady Wallace, Nélie inherited her husband’s collection on his death. When she died, she bequeathed all her possessions to the Institut de France, a bequest that led to the formation of two museums, one in Paris and one at Chaalis Abbey.42

For all three women, the wish to share their collections and to educate and inspire a wider public with the objects they had collected and enjoyed led them to found institutions that still survive and perform this function to this day. The greater success of the two collection museums (the Cooper Union Museum has moved and been renamed several times since its foundation) can perhaps be attributed to their being their creators’ erstwhile homes and gallery spaces. These hybrid public/private spaces reveal the female collectors’ identities more clearly than collections that were designed more for academic purposes than for pleasure and that had no real emotional tie to the buildings in which they were displayed.43

Intellectuals

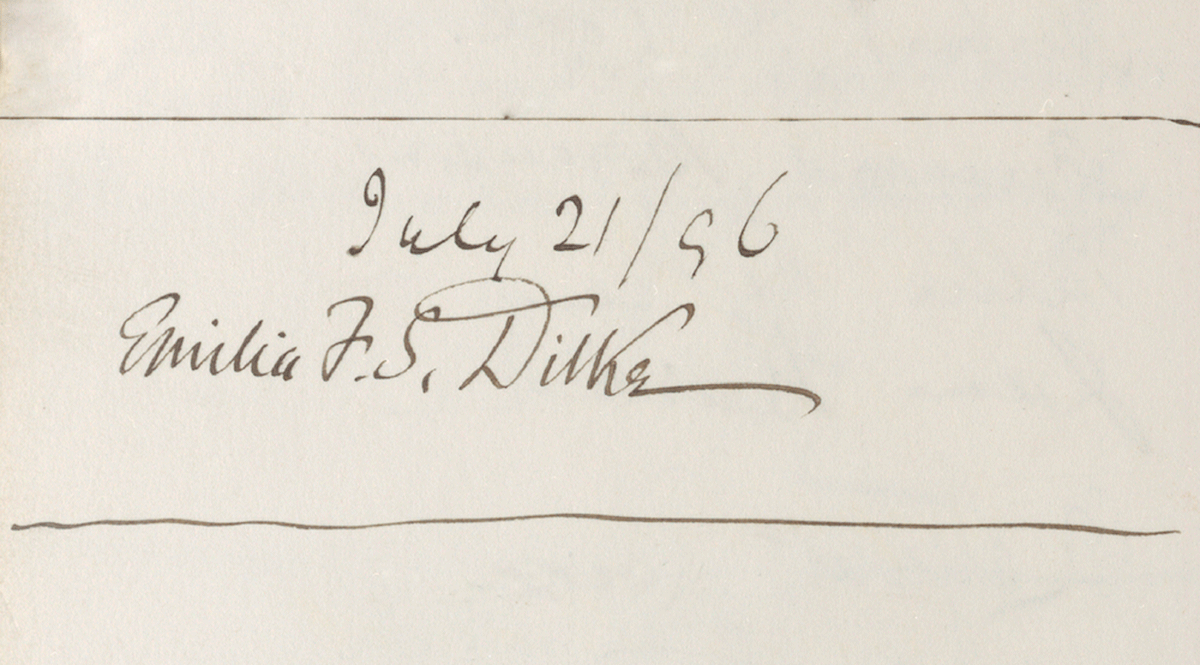

Although women were expected to enjoy art and to engage with it in an emotional sense, becoming an art historian or critic was far more difficult, especially as women were debarred from most university courses that would have enabled them to qualify academically.44 One woman who challenged these expectations was Emilia Dilke (1840–1904), whose visit to Hertford House is recorded in July 1896. Unusually, it appears that she visited alone (Fig. 9). She was an artist, art historian, and leader of the women’s trade union movement, with a great interest in women’s suffrage and legislation by and on behalf of women. Emilia studied art in South Kensington and later carved out a reputation for herself as an art historian and critic, especially of French art, publishing four books and numerous articles in spite of recurring bouts of ill health.45 She knew the collection at Hertford House so well that she was able to write the foreword to Émile Moliner’s 1903 publication on the Wallace Collection, and so must have visited many more times after the official opening of the museum in 1900. She was well aware of the limitations placed upon women by society but chose to work around them:

Ordinary life widens the horizon for men. Women are walled in behind social conventions. If they climb over, they lose more than they gain. It is therefore necessary to accept the situation as nature and society have made it, and to try to create for one’s self a position from which on peut dominer ce qu’on ne peut pas franchir [one can dominate that which one cannot overcome].46

Using this subtle form of domination, she worked determinedly for the benefit of other women. A friend remarked of her that she had ‘the strongest views about […] the selfishness of life’, and thought that leading a ‘purely individual life, however innocent, is a loss to the community and bad for the individual’.47 Emilia Dilke’s work for women perhaps shows this strong dedication to an ethic of service more strongly but her academic writing on art in the face of many private and societal obstacles also proves her determination to educate and to show that her own, and therefore other women’s, opinions and scholarship were as significant and worthy as those of her male contemporaries.

Increasingly, colleges for women were being founded in the latter half of the nineteenth century, although many were still unable to confer degrees. One family with several exceptionally intelligent female (and male) members were the Jex-Blakes. Sophia (1840–1912) was one of the so-called Edinburgh Seven, pioneering female medical students in Scotland. Her brother Thomas, who visited the collection twice accompanied by his children, was first a college don, then schoolmaster, chiefly at Rugby, and finally dean of Wells. Two of his daughters rose to fame due to their academic achievements: Katharine as a classical scholar and later mistress of Girton College, Cambridge; and Henrietta as a musician, teacher, and later principal of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford.48 Thus, both became heads of recently founded colleges for women, in spite of the fact that, at this point, women were not granted degrees from either Cambridge or Oxford. In 1920, during Henrietta’s time as principal, women were granted degrees from Oxford, but it would be another twenty-seven years before Cambridge did the same, by which time Katharine had long since retired. The sisters may have been among the Miss Blakes who accompanied their father in July 1880. Both signed their names in the book in June 1897, at which time they visited with their parents and several of their sisters.

Another visitor known for her scholarly work is Charlotte Guest (1812–1895), who, as Charlotte Schreiber, was also a great collector. Her best-known academic achievement is the translation of the Mabinogion, a Welsh series of folk tales with strong ties to Arthurian legend, originally compiled in Middle Welsh around the thirteenth century. Already a dedicated language scholar, Charlotte learned Welsh during her first marriage to Welsh ironworks magnate John Guest and published the Mabinogion in several volumes between 1838 and 1845. Her literary achievements during this time are all the more admirable considering that she also had ten children. Philanthropy was another of Charlotte’s interests. She was, by and large, a kind mistress to the workers left in her charge after her first husband had died. In that capacity she encouraged learning among the workers and their children and built a new school. During her second marriage, her interest turned to art collecting; she amassed a significant collection of playing cards and fans (now at the British Museum) and from 1865 focused primarily on collecting English porcelain, becoming an expert in this field. In 1885 she gave her collection to the South Kensington Museum as a memorial to her second husband. It can still be admired at the V&A to this day.49 She visited Hertford House in June 1889 with two of her granddaughters and her son or grandson, who shared the same name. Although Sir Richard’s collections of porcelain differ greatly from those she had collected, given the preference for French porcelain exhibited by the marquesses of Hertford, she must have admired the quality of the French items on view.

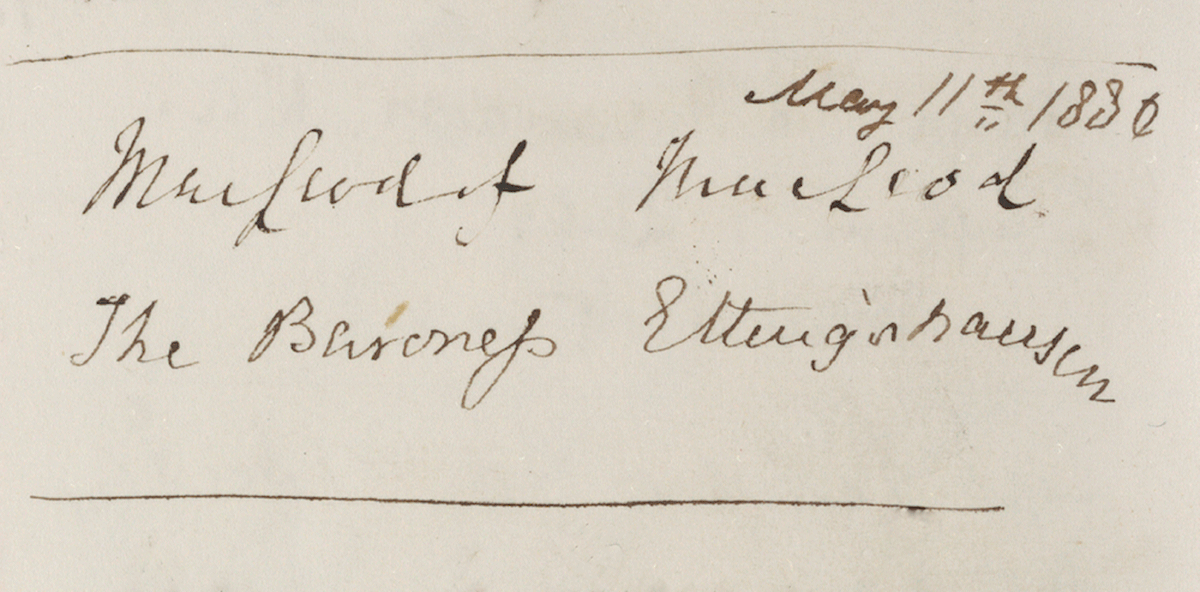

While many women stayed within the confines considered suitable for them, a few strayed into areas previously thought the sole province of men. Archaeology was one of these fields. Although women could become involved in recording and evaluating finds in museums in supporting roles, they rarely took an active role in fieldwork (Hill, Women and Museums, pp. 156–82). Baroness Hanna von Ettingshausen, a member of the Austrian nobility, followed an unconventional path, although her route, via her first marriage to an older man, began in a conventional manner. During an extended visit to London, she met Norman MacLeod, a Scottish laird who was impoverished by family debt and was, at that time, working at the South Kensington Museum. They visited Hertford House together in May 1880 and she married him a year later (Fig. 10). Travel to Scotland to visit the family estate on Skye changed her life, as she developed a great love of the island and its history. She became interested in archaeology and, with the help of several estate workers, led the excavations of two local brochs, Dun Beag and Dun Fiadhairt. Although she was not a collector in the strictest sense, her interest in the history of human endeavour on Skye led her to donate the finds from these excavations to the National Museums of Scotland, where they can still be found today. Even after MacLeod’s death and Hanna’s second marriage to Austrian education minister Count Baillet de Latour, she retained a great interest in the archaeology of Skye and continued with her excavations. Hanna was one of the early female fellows of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, being elected in 1915, one of only twelve female members in a society that numbered upwards of seven hundred.50

Concluding remarks

Many of the women who signed the Visitors’ Book are unidentifiable, details of their existence being lost to the ravages of time and the fact that women’s lives often went largely undocumented. The stories of the women whom I have managed to identify are both unusual and unexpected. Many of them fit into more than one of the categories into which they have been divided for the purpose of this article. A surprising number were international and seasoned travellers. Their lives were frequently interconnected because they moved within the same social circles. Several collected art. Largely privileged by wealth, education, and position in society, they were able to disregard or push aside ideas of conventionality. They all lived at a time when the professionalization of many skills and the formation of male-only interest societies excluded them from areas in which they otherwise would have flourished. They needed to establish themselves in all of these spaces by proving that their efforts were more than merely amateur, and that they could take their places in public life without detriment to themselves or to the public that they often sought to benefit through their efforts.

Women’s involvement with museums in the nineteenth century, whether as visitors, museum professionals, or exhibited artists, has seen an increase of interest and new scholarship in the last few years.51 Meaghan Clarke has drawn attention to women art scholars exploiting galleries as working spaces in much the same way as Emilia Dilke must have used the galleries of Sir Richard’s collection.52 More research into the specific visitors to Hertford House is needed in the many areas that fall beyond the remit of this article, such as a comparison of the visitors to this collection with those visiting other collections and institutions, a closer look at the differences and similarities in the art collections of those who visited Sir Richard’s collection, and further investigation into the social connections that tie many of these women together.

The one unifying factor for all of the above-mentioned women is that their lives intersect in this one particular place: they all visited the collections housed at Hertford House. Beginning from a simple signature, my research has revealed the diverse lives of these women who fleetingly passed through Sir Richard’s collection. The reasons for their visits are a complex mixture of academic interest, artistic inspiration, and the wish to see a collection that, unlike others, was not open to a general viewing public. Sadly, the Visitors’ Book does not record the visitors’ reactions to the collection; few wrote down their opinions. One hopes that, like Molly Hughes, they marched around with the thin, crimson catalogue of paintings provided (Higgott, ‘Most Fortunate Man’, p. 217), and ticked off many works of art they liked — and that they were able to look back on their visit as time extremely well spent.

Notes

- London, The Wallace Collection Archive (WCA), Hertford House Visitors’ Book, HHVB, MS note on preliminary pages. [^]

- See Suzanne Higgott’s article in this issue of 19. [^]

- Lady Wallace’s will (copy), WCA, HWF/LW/10; Suzanne Higgott, ‘The Most Fortunate Man of His Day’: Sir Richard Wallace: Connoisseur, Collector & Philanthropist (London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 2018), pp. 320, 323, 332, 338–44. [^]

- Kathryn Gleadle, Borderline Citizens: Women, Gender, and Political Culture in Britain, 1815–1867 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009). [^]

- Kate Hill, Women and Museums, 1850–1914: Modernity and the Gendering of Knowledge (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), pp. 2, 7–9, 109; Susan Armitage, ‘Introduction’, in Victor J. Danilov, Women and Museums: A Comprehensive Guide, intr. by Susan Armitage (Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, 2005), pp. 1–10 (p. 1). [^]

- Molly Hughes, A London Child of the 1870s (London: Persephone, 2005), p. 54. [^]

- Britain and the Narration of Travel in the Nineteenth Century: Texts, Images, Objects, ed. by Kate Hill (Farnham: Ashgate, 2016); Cynthia Gamble, Wenlock Abbey 1857–1919: A Shropshire Country House and the Milnes Gaskell Family (Much Wenlock: Ellingham, 2015). [^]

- International Medical Congress, 2 August 1881; First Colonial Conference, 18 May 1887; Society for the Encouragement of Fine Arts, 9 July 1885; Sieveking and Day families (17 and 10 Manchester Square), 2–3 August 1881. [^]

- The Empress Frederick Writes to Sophie, Her Daughter, Crown Princess and Later Queen of the Hellenes: Letters 1889–1901, ed. by Arthur Gould Lee (London: Faber and Faber, 1955), pp. 25–51. [^]

- Darling Child: Private Correspondence of Queen Victoria and the Crown Princess of Prussia, 1871–1878, ed. by Roger Fulford (London: Evans, 1976), p. 247. [^]

- Oliver Millar, The Victorian Pictures of Her Majesty the Queen, 2 vols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), cat. no. 1012; Delia Millar, The Victorian Watercolours and Drawings in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen, 2 vols (London: Wilson, 1995), cat. nos. 4966 and 4968. [^]

- Letter of Princess Victoria to Queen Victoria, 7 August 1890, Windsor, Royal Archives (RA), VIC/MAIN/Z/49/3. [^]

- Die Kunstsammlungen Ihrer Majestät der Kaiserin und Königin Friedrich in Schloss Friedrichshof, [ed. by Wilhelm Bode] (Berlin: Reichsdruckerei, 1896), pp. 10–14. [^]

- Thomas Neville Bonner, ‘Medical Women Abroad: A New Dimension of Women’s Push for Opportunity in Medicine, 1850–1914’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 62 (1988), 58–73 (pp. 62–64). [^]

- M. A. Elston, ‘Anderson, Elizabeth Garrett (1836–1917)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/30406>; Rhoda and Agnes Garrett, Suggestions for House Decoration in Painting, Woodwork and Furniture (London: Macmillan, 1877). [^]

- Letter from Louisa to her mother, 27 September 1914, Papers of Louisa Garrett Anderson, Women’s Library, London School of Economics (LSE), 7LGA/2/1/09. [^]

- Flora Murray, Women as Army Surgeons, Being the History of the Women’s Hospital Corps in Paris, Wimereux and Endell Street, September 1914–October 1919 (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1920), pp. vii, 146, 164; Wendy Moore, Endell Street: The Trailblazing Women Who Ran World War One’s Most Remarkable Military Hospital (London: Atlantic, 2020); Jennian Geddes, ‘Anderson, Louisa Garrett (1873–1943)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/62050>. [^]

- Lord Ashcroft, ‘Only Woman to Win a Victoria Cross: Elizabeth Webber Harris Saved Soldiers with Cholera’, Express (18 March 2015, updated 8 April 2015) <https://www.express.co.uk/news/history/564600/Only-woman-win-Victoria-Cross-Elizabeth-Webber-Harris-saved-soldiers-cholera>; ‘Elizabeth Matthews (1834–1917)’, The MAN & Other Families <https://www.manfamily.org/about/other-families/matthews-family/elizabeth-matthews-1834-1917/> [both accessed 28 October 2020]. [^]

- Letter from Louisa to her mother, 27 September 1914, LSE, 7LGA/2/1/09. [^]

- Jose Harris, rev., ‘Lytton, Lady Constance Georgina Bulwer- (1869–1923)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/37705>. [^]

- Jessica Lack, ‘The Role of Artists in Promoting the Cause of Women’s Suffrage’, Frieze (2 September 2018) <https://frieze.com/article/role-artists-promoting-cause-womens-suffrage> [accessed 28 October 2020]. [^]

- Life of Octavia Hill as Told in Her Letters, ed. by C. Edmund Maurice (London: Macmillan, 1913), pp. 64, 79, 103, 105, 116, 136, 172–74, 204, 217. [^]

- John Price, ‘Octavia Hill’s Red Cross Hall and Its Murals to Heroic Self-Sacrifice’, in Octavia Hill, Social Activism and the Remaking of British Society, ed. by Elizabeth Baigent and Ben Cowell (London: University of London Press, 2016), pp. 65–90 <www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv4w3whm.11> [accessed 28 October 2020]; Gillian Darley, ‘Hill, Octavia (1838–1912)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/33873>. [^]

- Stephen Duffy and Jo Hedley, The Wallace Collection’s Pictures: A Complete Catalogue (London: Trustees of the Wallace Collection, 2004), pp. 431–32. [^]

- ‘Gräfin Elisabeth von Münster-Ledenburg’, Geneagraphie: Families All Over the World <http://www.geneagraphie.com/getperson.php?personID=I629570&tree=1>; Hugo Rasmus, ‘Gröben, Selma Gräfin von der’, Kulturportal West–Ost <https://kulturportal-west-ost.eu/biographien/groeben-selma-grafin-von-der-2> [both accessed 28 October 2020]. [^]

- For the bequest, see, for example, ‘Rich Treasures for England’, New York Tribune, 28 February 1897, p. 2; and for the opening of the museum, see ‘News of Two Capitals: London’, New York Tribune, 24 June 1900, p. 1. [^]

- See Rebecca Tilles’s article in this issue of 19. [^]

- Robert W. Torchia, American Paintings of the Nineteenth Century: Part II (Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1998), pp. 113–15. [^]

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: Fortieth Annual Report for the Year 1915 (Boston: Metcalf, 1916), p. 121. [^]

- John Chu, The Pictures at Polesden Lacey ([n.p.]: National Trust Books, 2017), p. 3. [^]

- ‘The Mystery of Mrs Greville’s Jewellery’ <https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/polesden-lacey/features/a-peek-at-maggie-grevilles-jewellery> [accessed 28 October 2020]; Richard Davenport-Hines, ‘Greville [née Anderson], Dame Margaret Helen (1863–1942)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/51986>. [^]

- See the discussion of Yolande Lyne-Stephens and Joséphine Bowes by Laure-Aline Griffith-Jones and Lindsay Macnaughton, respectively, in this issue of 19. [^]

- J. Gilliland, ‘Taglioni, Marie (1804–1884)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/26915>; Sarah C. Woodcock, ‘Margaret Rolfe’s Memoirs of Marie Taglioni: Part 1’, Dance Research, 7 (1989), 3–19; ‘Part 2’, 55–69. [^]

- Michael Holroyd, A Strange Eventful History: The Dramatic Lives of Ellen Terry, Henry Irving, and Their Remarkable Families (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), pp. 9–10, 49–51. [^]

- Kadja Grönke, ‘Alma Haas’, Europäische Instrumentalistinnen des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts, 2015 <http://www.sophie-drinker-institut.de/haas-alma> [accessed 28 October 2020]; ‘Alma Haas [obituary]’, Musical Times, 74 (1933), p. 177. [^]

- Jane S. Smith, Elsie de Wolfe: A Life in the High Style (New York: Atheneum, 1982), pp. xvi, 3, 55–57, 63; Nina Campbell and Caroline Seebohm, Elsie de Wolfe: A Decorative Life (New York: Panache, 1992), pp. 7–11. [^]

- Deborah Cherry, Painting Women: Victorian Women Artists (London: Routledge, 1993), p. 9. [^]

- ‘Miss Ella Casella’, in Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database, 2011 <https://sculpture.gla.ac.uk/view/person.php?id=msib5_1208550230> [accessed 28 October 2020]. [^]

- For the samples of textiles donated to the Met, see search results for ‘Mrs. Boudinot Keith’ at <https://www.metmuseum.org> [accessed 28 October 2020]. [^]

- Morris Carter, Isabella Stewart Gardner and Fenway Court (London: Heinemann, 1926), pp. 35–47, 59–88, 182–98. [^]

- Smith, pp. 96–97; Eleanor G. Hewitt, The Making of a Modern Museum ([n.p.]: written for the Wednesday Afternoon Club, 1919); Elizabeth Bisland: Proposed Plan of the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration ([n.p.]: [n.pub.], 1896); Treasures from the Cooper Union Museum (Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1967), pp. 7–9. [^]

- Musée Jacquemart-André: guide officiel ([Paris]: Culturespaces, 1997), p. 7. [^]

- Anne Higonnet, A Museum of One’s Own: Private Collecting, Public Gift (Pittsburgh: Periscope, 2009). [^]

- For detailed discussions of nineteenth-century women writing about art, see Old Masters, Modern Women, ed. by Maria Alambritis, Susanna Avery-Quash, and Hilary Fraser, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 28 (2019) <https://19.bbk.ac.uk/issue/116/info/> [accessed 28 October 2020]. [^]

- Hilary Fraser, ‘Dilke [née Strong; other married name Pattison], Emilia Francis, Lady Dilke (1840–1904)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/32825>. [^]

- Sir Charles W. Dilke, ‘Memoir’, in Lady Dilke, The Book of the Spiritual Life (London: Murray, 1905), pp. 1–128 (p. 55). Translation from the French is my own. [^]

- Betty Askwith, Lady Dilke: A Biography (London: Chatto & Windus, 1969), p. 195. [^]

- Fernanda Helen Perrone, ‘Blake, Katharine Jex- (1860–1951)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/48441>. [^]

- Jacqueline Yallop, Magpies, Squirrels & Thieves: How the Victorians Collected the World (London: Atlantic, 2011), pp. 130–31, 156–64, 177–85; Angela V. John, ‘Schreiber [née Bertie; other married name Guest], Lady Charlotte Elizabeth (1812–1895)’, ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/24832>. [^]

- Katinka Dalglish, ‘The Countess, the Chief and the Two Brochs’, Answers on a Postcard, 8 February 2016 <https://answersonapostcard.weebly.com/answers-on-a-postcard/the-countess-the-chief-and-the-two-brochs>; Statement of Significance: Dun Struan Beag (Edinburgh: Historic Environment Scotland, 2020) <https://www.historicenvironment.scot/archives-and-research/publications/publication/?publicationId=d25087cb-becf-42d7-aa71-a6c900ff0a04> [both accessed 28 October 2020], pp. 6, 11; Fred T. MacLeod, ‘Notes on Dun Iardhard, a Broch near Dunvegan, Excavated by the Countess Vincent Baillet de Latour, Uiginish Lodge, Skye’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 49 (1914), 57–70 (p. 57). [^]

- Helen Rees Leahy, Museum Bodies: The Politics and Practices of Visiting and Viewing (London: Routledge, 2016); Hill, Women and Museums. [^]

- Meaghan Clarke, ‘Women in the Galleries: New Angles on Old Masters in the Late Nineteenth Century’, 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 28 (2019) <https://doi.org/10.16995/ntn.823>. [^]